About a month ago I was riding the 7 line on the Paris Metro, jotting furiously in a pocket notebook, as is my wont, and a stranger, a guy with Shannon Hoon-ish locks who I’d have guessed to be somewhere in his twenties, noticed a name and address that I’d written down in its pages. I should explain that I divested myself of my smartphone some time ago, consequently losing on-the-go access to the convenience of Google Maps and the like, and this requires me to prepare for any outing into unaccustomed territory by scrupulously writing out directions in advance. This is of course a massive annoyance, not least to the friends and loved ones who are forced to shoulder the burden of my technophobia, and very likely comes off as an infuriating affectation, but one of the comforts of aging—perhaps the only one—is that, if you’re doing it right, you give ever less fucks about looking like a ridiculous prat. The address in question was 34 rue Daubenton, in the 5th arrondissement near the University of Paris III, and what the stranger asked me was “Allez-vous à la Clef?”

In my life as a repertory rat, this is the first and only time that a stranger has ever seen fit to strike up a conversation with me on the basis of any of the telltale signs of morbid cinephilia that are habitually dangling from my bedraggled person—contrary to popular belief, toting Tag Gallgher’s John Ford on one’s morning commute does not function as a piece of PUA flare. It’s illustrative of the degree to which the Cinéma la Clef Revival, a communally programmed and operated squatter’s cinema in the Quartier Latin who’ve spent the entire month of February under threat of eviction, captured the Parisian imagination this winter.

The La Clef Revival phenomenon can’t be explained by clichés about ardent French cinephilia; in Paris, as everywhere around the world, hardcore moviegoers are graying, aging, and shuffling off this mortal coil. A friend coming from a late January Cinémathèque Française repertory screening of Histoire de Marie et Julien (2003), part of the Cinémathèque’s Jacques Rivette retrospective, reported an audience of about a half-dozen, with an average age of approximately 88. This makes perfect sense, because what young person in their right mind would want to find themselves stuck in Bercy for an evening? In 2005 the Cinémathèque left behind its space in the bowels of the Palais de Chaillot, its residence since 1963, for a new home in that deathly dull 12th arrondissement neighborhood, settling into the former American Center building by starchitect Frank Gehry, which looks like a rejected design for a correctional facility in Fort Wayne, Indiana that one of Gehry’s assistants happened to find lying around when the commission came in.

La Clef Revival enjoys a considerably more propitious location for drawing the youth crowd than the Cinémathèque. The stretch of the Left Bank in the vicinity of the Sorbonne is home to more cinemas per square kilometer than perhaps anywhere else in Europe, if not the world—though this bastion of movie mania has suffered under the besiegement of urban redevelopment. A map of Saint-Germain-des-Prés featured in Axel Huyghe and Arnaud Chapuy’s recent volume on the storied Le Saint-André-des-Arts cinema allows one to see just how many movie theaters have turned off their lights since the heyday of the 1950s, back when Rivette was the holy terror of the trivia nights at the Studio Parnasse in Notre-Dames-des-Champs. Further cinema casualties have been inflicted by Covid closures, like the charming Accatone on rue Cujas1, snapped up after its shuttering by the neighboring Hôtel Excelsior. I’m not sure if they plan to keep it as a cinema space, but at any rate it won’t be named after a Pier Paolo Pasolini movie, and this seems to me an obvious loss for world culture.

That Paris isn’t quite itself anymore is a common complaint among Parisians, who’ve seen rents spike as absentee Airbnb renters infest the center city, inspiring many to light out for cheaper, grungier destinations like Marseilles and Brussels, which promise a temporary reprieve from the onslaught of corporate bulldozers—temporary, of course, because it seems they’ll arrive everywhere eventually, and flatten everything in their path2. This goes some ways towards explaining why La Clef Revival, a bulwark against the marching profit motive in the heart of Paris, has become a cause to rally to. As various well-known well-wishers put in appearances in the leadup (and aftermath) of a threatened Feb. 1st eviction by force, still looming at the time of this writing, it felt like the hottest ticket in town.

Having heard about La Clef Revival for some time from friends both at home and abroad, I set out to attend the cinema’s 8:30 screening of Une chambre en ville, being presented by Leos Carax on the evening of January 31st—potentially La Clef’s final screening. The line of disconcertingly good-looking, stylish kids that wrapped around the block 45 minutes before showtime said in no uncertain terms: “Better luck next time, Gramps.” Granted that the prospect of seeing police truncheons and tear gas lent the evening a certain grim allure of possible “value-added” entertainment, but the sight of a large number of hip Parisians who could just as easily have been having sex or swirling around in K-holes or whatever it is that young people do these days instead clamoring to watch a 1982 Jacques Demy movie together was intriguing and more than a little heartwarming. What exactly was going on here?

An abridged history: La Clef was opened as a three-screener, de cinéma d’Art & Essai La Clef, on October 10, 1973, with salles of 226, 97, and 86 seats, as well as an attached restaurant, Auberge de La Clef. This was under the management of one Claude Franck-Forter, the son of children’s clothing manufacturers from Troyes who had a small family fortune to play with and a yen to try his hand in film exhibition. I would’ve bet good money that La Clef had been built as a porno palace, given the fact that its façade is graced by a rather phallically suggestive key, but Monsieur Franck-Forter puts this theory to rest in a history of the La Clef hosted on their website, explaining: “For me, a key represents a mythical, almost magical object, because its etymology in several languages describes either something that allows access to be limited, or the opposite, that is, to open it widely.” The only poster legible in the rare vintage image of La Clef online is for Francesco Rosi’s Lucky Luciano (1973), and the programmer through the Franck-Forter era was the perfectly respectable Bernard Martinand, a co-founder with the late Bertrand Tavernier of the ciné-club Nickel Odéon and a longtime associate of Henri Langlois at the Cinémathèque, where he would serve in various capacities after his time at La Clef. Guess I’ve just got a dirty mind.

After seven-plus years doing a brisk business with students, playing revival titles in mornings and late nights and new releases in-between, La Clef hit the skids at the beginning of the ‘80s. This situation Franck-Forter attributes to the new availability of inexpensive color televisions and a new hesitancy among distributors to give big-budget movies to small houses: the small fry gets screwed over, plus ça change. After closing the cinema in 1981, Franck-Forter sold La Clef to Comité d’Entreprise de la Caisse d’Épargne d’Île de France (CECEIDF), the works council of a regional branch of the Caisse d’Épargne cooperative banking group, since 2008 merged with the Groupe Banque Populaire, and still the building’s present—or, more accurately, absent—owners.

Following the purchase, Caisse d’Épargne kept two of the La Clef screens functioning as cinemas—now down to 120 and 65 seats—while using the rest of the premises as a cultural center for their employees. By 1990, the screens were being made available for outside organizations to program, most notable of these Images d’Ailleurs, who focused on screening works by African diaspora filmmakers and films from the Arab world; this was the brainchild of Togo-born Sanvi Panou, a “slameur” poet who’d appeared briefly as an actor in Jean-Luc Godard’s Week-End (1967) and recorded, as Alfred Panou, with the Art Ensemble of Chicago in 1969. (You can listen to his “Je suis un sauvage” here; it’s a hot track.) Around 2009-10, a new programming team moved in, consisting of Dounia Baba-Aissa, Raphaël Vion, and Nicolas Tarchiani, who continued to work along the lines established by Panou, until, in 2015, Caisse d’Épargne announced their decision to sell the cinema, closing its doors in April of 2018. This is where the Association Home Cinema comes in.

In September, 2019, the Association Home Cinema (hereafter AHC) illegally occupied La Clef, and began a program of free daily screenings that has continued to the present day. A court order was issued demanding the group leave the space by December 19th of that year; an appeal of the decision was duly filed, and during the wait for a court date, the world stopped functioning. This effectively operated as a stay of execution for AHC, and while most of Paris—indeed, the world—went into work-from-home hibernation, the AHC was in a frenzy of beaverish activity, including the publication of a house fanzine, workshops, and regular broadcasts from a webradio station. And, vitally, as screens across Paris went dark, La Clef Revival soldiered on with public outdoor screenings projected on the cinema’s outer wall. I’m not going to speculate as to if the screens inside were being made use of during the same period—that can be the AHC’s little secret—but I emphatically hope that they were.

I finally wedged my way into the doors of La Clef Revival on the evening of Wednesday, February 2nd, to see Claire Denis present a 35mm print of her 1990 S’en fout la mort (No Fear, No Die). In point of fact, I didn’t see either Denis in the flesh or the print, but rather a simulcast of her introduction and a low-resolution digital projection in the smaller downstairs “overflow” theater. This seemed to me entirely reasonable, as I’m a late-to-the-party outside interloper, and anyways I can enjoy some heavily artifacted deep blacks when I’m in the right mood.

Denis, who since my visit has returned to La Clef to present her 1994 U.S. Go Home, is a particularly ardent supporter of this cinema which hasn’t lacked for support from both famous names and rank-and-file moviegoers. In response to an offer to buy La Clef made in early 2021 by the entrepreneurial firm Groupe SOS—an offer rebuffed by the AHC—a letter of support was issued by la Société des Réalasiteurs des films, a filmmakers’ association, with signees including Denis, Alain Cavalier, Bertrand Bonello, Vincent Macaigne, and Nicole Brenez. (The last-named was instrumental in one of La Clef Revival’s great programming coups, coaxing a seven-film carte blanche program out of Jean-Luc Godard, a figure not known for keeping a particularly high public profile, in October of 2020.) With each new hurdle faced by La Clef Revival, statements of support have continued to spill in: from filmmakers, like that old anarchist Luc Moullet, from festivals (Cinéma du Réel), and from other cinemas (Brussels’ Cinéma Nova and Marseilles’ Videodrome 2, among the finest in the Francophone world.)

Since receiving its eviction notice, La Clef Revival has ramped up their screening activity, routinely opening shop at 6 AM. (I genuinely believed that I would make it out to a before-sunrise screening of Gregg Araki’s 1997 Nowhere on the 9th, but where the mind is willing, the flesh is sometimes weak…) During this all-hands-on-deck period, a cavalcade of filmmakers have stopped by to present their work and show solidarity, among them Alejandro Jodorowsky, Marie Losier, Serge Bozon, Sébastien Lifshitz, and Wang Bing, who introduced his Man with No Name (2010) earlier on the day of Carax’s Une chambre en ville screening. The significance of Carax’s choosing to screen a musical drama, made by Demy at the outset of the rapacious ’80s, that unfolds against the backdrop of a skull-cracking labor dispute in c. 1955 Nantes was, I trust, lost on no-one.

Prior to the theaters filling up on my Wednesday night visit to La Clef Revival, a quartet of AHC members passed the mic to deliver addresses to the crowd milling in the lobby, a cozily junky space where beer and box wine was on sale for two Euro a cup, its walls plastered with flyers and posters, most prominently one for Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment (1968) overlooking a badly out-of-tune looking upright piano.

The general content of the oratory—at least as I could discern with a toddler’s ability to comprehend spoken French of the rat-a-tat-tat Parisian variety—can be gleaned from a recent post at Andy Rector’s Kino Slang blog, which offers the AHC platform statement, read aloud that evening, in a translation courtesy of filmmaker Valérie Massadian, who presented her 2011 Nana at La Clef Revival on the 1st of February. (Rector’s also links an admirable English-language primer on La Clef Revival from the Romanian film magazine Films in Frame, authored by Flavia Dima, which is further recommended reading.)

If I don’t feel compelled to dwell on the politics of the AHC or the nature of the programming at La Clef Revival, it’s because my position towards the entire endeavor—which is one of unequivocal support—is based on general principles rather than any ideological sympathy or enmity.

The first of these principles is that a cinema being programmed with passions and prejudices, whatever they may be, is in almost every case, superior to the absence of that cinema. If La Clef Revival, per their platform, are inclined “project and produce queer, anti-racist, radical films,” well, hell, that’s a-okay by me, I can get down with plenty of that stuff… but any question of aesthetic or ideological alignment is strictly an afterthought. If the only occupant of the La Clef was a filthy, scabby crank with a 16mm projector playing a monthlong program of Sam Wood at his most lugubrious, I’d still be all for it.

Over the last couple years, I’ve had the second track from John Cale’s 1975 album Slow Dazzle stuck in my craw—the one that features Cale bellowing “They’re taking it all away” on the hook. It’s a catchy little ditty, sure, but it also seems an appropriately despairing anthem for times in which the earth is being steadily and purposefully denuded of every routine pleasure that makes life worth living. This certainly isn’t limited to cinemas—real cinemas, not those suburban outlet store equivalents that exist as a dumping ground for sixteen screens of Disney dross—but the aggression on that front has been particularly virulent, which is why I’ve had to dutifully write about six hundred versions of this piece through the years, addressing matters from Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop’s attempt to oust the Friends of the Loew’s from their rightful home in Journal Square to the Bolsonaro government’s callous, unforgivable treatment of the Cinemateca Brasileira.

The act gets a little tiresome, admittedly, but then this death-by-a-thousand-cuts attack on the greatest popular artform is pretty tiresome, too, so here we go again. I write this in the aftermath of news that San Francisco’s Castro Theatre, a cinema since 1922, will become a venue for coders to guffaw at the comedy stylings of Jim Gaffigan, and of a cry for help from an association of exhibitors in Italy, a country where 500 of a total 3,600 screens have stayed dark post-Covid. Times change, yes, but there are people high up who have their thumb on the scale when it comes to determining how they’ll change, and I’m very far from being convinced that business closures commanded with insufficient promise of compensatory remuneration and loss-leading Silicon Valley juggernauts running on endless influxes of venture capital flattening competition and dismantling anything that keeps people away offline for even a solitary second could be called “the invisible hand of the market.”

Our decisions have been made for us and we’ve been done dirty, from dead-tech DCP to archives jealously guarding their holdings under lock-and-key to non-profit arts organizations in the death grip of numbskull board members insensate to tradition and invariably enthralled by the siren song of techie novelty, their rheumy eyes briefly lighting up at the words “podcast” or “VR.” The case of La Clef Revival is rather cut-and-dry, but I wouldn’t be averse to every CVS and supermarket that used to be a movie theater being reconverted to its original function at gunpoint. I’m on the side of cinema, and at this juncture, that doesn’t leave space for quibbling over property law.

The second reason for my support of La Clef Revival is a conviction that culture that comes from the ground up—that is, people united by common cause just getting together and doing a thing—is almost invariably superior to that which comes from the top down.

Before heading to La Clef, I met up with a friend—the Canadian filmmaker Sofia Bohdanowicz, now based in Paris, responsible for some of the images accompanying this piece—at Ciné-Images, a consummately excellent movie poster shop in the 7th arrondissement. Ciné-Images is located across the street from the presently-under-renovation Cinema La Pagode, an ersatz Japanese-style “temple” built in 1896 by architect Alexandre Marcel which, save for a brief closure during the Occupation, operated continually as a cinema from 1931 to 2015.

The renovation of La Pagode, by all accounts badly needed, is occurring at the behest of—and with the funds of—Charles S. Cohen, the real-estate mogul-turned-arthouse impresario who is owner of the Landmark Theaters and Curzon Cinemas chains, and the rightsholding custodian of the collection of classic film titles amassed under dubious pretexts by collector/slimeball Raymond Rohauer, a rather infamous character in silent film circles.

It is, of course, better that La Pagode should get a fresh coat of paint and be reopened to showing movies than that it be turned into a Carrefour, but let’s be realistic: it probably won’t be distinguished by anything other than architecture, because it’s a Cohen cinema, and before he’s anything else, Cohen is a money guy, long on cash and short on taste. Some may recall an earlier high-profile venture into exhibition by Cohen, his purchase and rehab of New York’s Quad Cinema, reopened in 2017. The official story was that Cohen, inheritor of a small empire, was a thwarted cinephile who’d joined the family business out of duty; now, having done his diligence in increasing the net worth of Cohen Brothers Realty by however many billions, he was free to play patron, a modern-day Medici of the Seventh Art, bringing on honest-to-God programmers at his theater and spending his amassed lucre on shipping 35mm prints of Just Jaeckin movies to New York with no thought for the bottom line, because a big pile of money to burn can go a very long way, as Charles Foster Kane observed when describing his losses in the newspaper business defiantly to befuddled bank bean-counter Mr. Thatcher.

But then, almost nobody really operates that way, at least not for long. Inherited wealth may in some cases be squandered splendidly—I’m thinking of Andrew Getty, who before his death in 2015 poured his inheritance into making a genuinely vile horror movie, The Evil Within (2017), and some would say that Annapurna had a pretty good run before the plug was pulled. But if you have enough money to afford to lose a little on a passion project, you probably got that pile by thinking about balance sheets above all, and that habit dies awfully hard, and so the Quad today has settled into being a perfectly unexceptional “arthouse” cinema that presumably pays for itself, just as, in all likelihood, La Pagode will.

The circumstances that allow La Clef Revival to operate are particular to France, which has a proud tradition of amateur operated cine-clubs—like the Nickel Odéon—and a system of legal concessions in place to ensure the continued existence of such groups, as well as “associative” cinemas like La Clef Revival, the last such institution in Paris. The Films in Frame piece, cited earlier, quotes from a 2012 report from the Opale cultural resource and social/solidarity economy center, which describes the associative cinemas as “answer[ing] to a social demand rather than the laws of the market.”

Dima writes from a Romanian perspective, addressing an audience of cinephile countrymen and -women who’ve faced unique adversity. Aside from the paucity of serviceable materials available to screen—addressed in this interview that I conducted last year with director Radu Jude—there’s the small matter of a catastrophic 2015 fire at the Colectiv nightclub, with subsequent scrutiny of the structural integrity of entertainment venues of all kinds leading to the closure of most of central Bucharest’s cinemas. While knowing full well that French cinephiles face different challenges—and enjoy different resources—than those in Romania, Dima asks: What can we in Romania take away from the example of La Clef Revival? And what, for that matter, can cinephiles around the world learn from it?

This brings me to the final reason for my support of Cinéma La Clef Revival: excepting cases in which one is subjecting others to harm without their consent to do so, I am almost without exception in favor of people being bad and doing things that they’re not supposed to—i.e. continuing to operate a cinema during a proclaimed public health crisis.

I first heard of La Clef in mid-2020 from an American friend who was waiting out the first wave of Covid on the Continent, and who had been to the theater several times. (“They fed me pasta for free the first time I went,” he enthused to me via WhatsApp.) His experience left me deeply jealous, and deeply embarrassed that nothing equivalently insubordinate was happening on the home front.

As someone who managed to criss-cross the Atlantic a few times during the plague years, I had some opportunity to observe a contrast in attitudes between friends in New York City and Europe, and the comparison did not—a handful of reckless, beloved degenerates aside—tend to favor the North Americans. The reasons for this contrast aren’t hard to explain, at least as regards the United States: the bare minimum of provision was made for out-of-work citizens, our health care system is comically atrocious, and, in the face of laggardly, disorganized, altogether fuddled government response, the burden of responsibility for “stopping the spread” was thrust onto the individual, resulting in the creation of a generation of presumably well-meaning neurotics who will never again leave the house without N95 masks covering every square inch of their bodies. The campaign to make people believe that compliance was synonymous to conscientiousness was ruthlessly effective, and as it was being pushed ahead, common sense went out the window. The divisiveness of the Trump presidency engendered a politicization of the pandemic that has continued to this day: good lefties had to treat a disease with very specific demographic targets as the bubonic plague, good righties had to laugh it off all the way to the ventilator. (Don’t take my word for it, you can read about it in the Grey Lady!)

I have not observed quite the same Manichean divide in Europe, or at least in France. In Marseilles last summer I stumbled across a rally protesting the then-recent implementation of Passe Sanitaire laws, rendering the right to free movement in the social sphere contingent on providing proof of vaccination, and a local friend confirmed my impression of the unusual makeup of the gathering, composed of groups representing the far-right, the far-left, and just about everything in-between. This is an anecdotal observation, only worth about as much as such things usually are, but it may help to explain how a leftist collective operation like La Clef Revival could be celebrated for continuing to operate during the pandemic in Paris, while anyone in New York would’ve been pilloried for doing the same thing.

Some might say that inviting people to congregate and watch movies during a pandemic, running the risk as such a thing might of spreading further contagion, falls under my abovementioned “harm without consent” category. I would respond that there was more harm in abandoning the public sphere en masse to be razed and reshaped by human-hating tech billionaire shysters who determine our fates whilst sitting cross-legged in a tent at Burning Man, and that if you were a relatively healthy young person who wasn’t passing the pandemic living in close quarters with an octogenarian, there was no compelling reason that you shouldn’t have been able to, if so inclined, treat yourself to a nice little movieshow in the company of a few friends and strangers. Anyhow, we all know that Covid germs just float up to the ceiling in movie theaters.3

It’s almost certainly unproductive to spend the rest of our natural days relitigating who was laudably responsible and who was and derelict of duty to their friends and neighbors through the Covid years, but that’s never stopped a good, old-fashioned clamor for moral high ground. At least the tut-tutting has died down a bit these days, in the streets and online, particularly since the New War dropped—an event which may make rallying behind a squatter’s cinema in Paris seem less crucial than it did, say, a month ago. Here I feel compelled to cite a quotation from an undated letter by Godard, addressed to the Cinémathèque’s Henri Langlois, which graces the side of La Clef Revival:

“What consoles me, anyway, is knowing that there is always somewhere in the world, at any time––when it stops in Tokyo it starts again in New York, in Moscow, in Paris, in Caracas––there is always, I say, a little monotonous noise, but intransigent in its monotony, and this noise is that of a projector projecting a film. Our duty is that this noise never stops.”

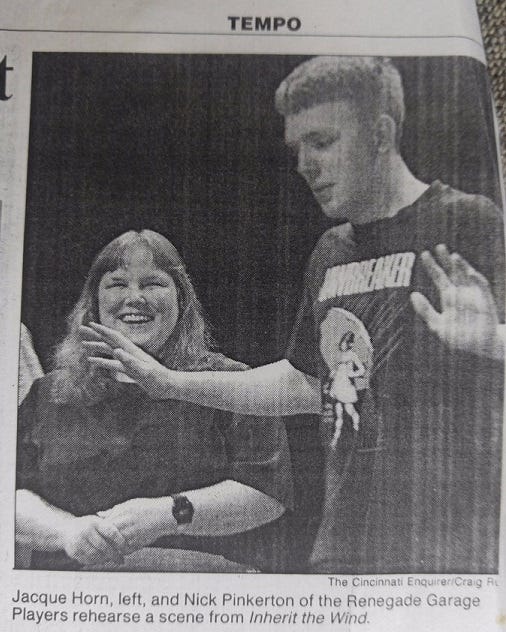

When I was about seventeen, I played Henry Antrobus in an amateur theatrical of Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth. This wasn’t a high school production—I would never sully myself with an official extracurricular!—but rather the work of an organization called the Renegade Garage Players, who staged classics with casts made up of teenagers and mentally and physically disabled adults with, as you might imagine, rather avant-garde results.

Wilder’s play was first presented in 1942, not long after the United States’ entry into World War II; my memory is a little hazy on most of what happens in it, but I can tell you the play is an extended allegory for the life of man- and womankind, and the various tribulations we as a species have faced through the millennia, written in a moment fraught with fear for the future. What I can recall of it most vividly is the absolutely piercing line-reading that the young woman playing my wife gave when upbraiding the family maid for neglecting the hearth: “Sabina!” she would say, with a shrewish shriek that rattles me to this day, “You let the FIRE go out!”

The fire, if I remember rightly, serves as a heavy-handed metaphor for civilization, and as such must be stoked at all costs; at any rate, the line has been bouncing around my head for twenty-some years, and will probably keep rattling around in there until closing time. I bring it up only by way of saying that I’ve always liked janky spit-and-tape operations like Renegade Garage Players, and I like people who keep the projector going, and I like people who tend to the fire, and I like what they’ve done at La Clef Revival, very much.

You can donate to La Clef Revival here.

You can slap your John Hancock on a Change.org Petition here.

Biographers will be fascinated to know that I watched Andy Warhol’s Flesh (1968) here in 2003 with my girlfriend at the time.

A few years ago I was staggered when a Russian friend casually used the phrase “gentrified Siberia.” Wait… they gentrified Siberia?

Source: Idk, it seems correct.