Especial thanks are due here to Gabe Klinger, São Paulo native, current resident of the city, and co-curator of the Cinema da Boca do Lixo retrospective at the 2012 Film Festival Rotterdam; in a very literal way, this piece would not have been possible without his assistance. Additional information on the current threats posed to the Cinemateca Brasileira and to Brazilian film culture in general, and on resources to assist the institution and its employees in their hour of need, come from Fábio Andrade and Ela Bittencourt.

I have only seen Jean Garret’s Fuk Fuk à Brasileira (Fuck Fuck Brazilian Style, 1986) in the manner that I have seen most of the Brazilian films that I’ve seen affixed with the scurrilous “Cinema da Boca do Lixo” label: on a contraband file, often of appallingly low quality, passed along by some fellow degenerate, usually with subtitles provided by an amateur enthusiast, if indeed subtitles are to be found at all. Yet I know that a fairly fresh 35mm print of Fuk Fuk à Brasileira does exist, because it was struck, by the Cinemateca Brasileira, for a 2012 program of Cinema da Boca do Lixo at the Film Festival Rotterdam, using public funds. The miraculous perversity of a public institution supporting such a thing I can only explain by describing Fuk Fuk à Brasileira and the Cinema da Boca do Lixo, a low-born, sublimely sketchy popular phenomenon; the poetry of it all I can only explain by discussing the Cinemateca Brasileira and the role of the cinematheque in guarding film history, which I will come to in due time.

Fuk Fuk à Brasileira, a sort of sci-fi porno picaresque, stars Chumbinho, a little person actor standing around three feet tall and a Boca do Lixo workhorse, as “Siri” (Crab), a mute who narrates his story telepathically. As the film begins, he is working as a houseboy for an upper-class couple, Mr. Julio and Mrs. Lia, who are so accustomed to his presence that when he comes to deliver a glass of refreshment, they don’t bother to stop fucking doggystyle in front of a framed picture of Marilyn Monroe. (The sex is real, explicit, and frequent.) A peaceful existence that consists of Siri’s wearing a motocross helmet and punching a medicine ball while the lady of the house masturbates in front of him, orally servicing her while she stuffs her face with pretzel sticks in bed, and being showered with gift dildos from Mr. Julio, comes to an abrupt end one night as the couple are hosting a guest for a threesome. Mr. Julio orders Siri to fetch some lubricatory butter, but his announced ambitions break up the party. “She ain’t no Maria Schneider, but I’m gonna fuck her ass,” says Mr. Julio; “Listen, you ain’t no Marlon Brando either, ya know,” replies the guest, fleeing. Mrs. Lia, too, exits, upon sensing the unpleasant viscosity of the unguent; it’s margarine and, as she explains in a huff, “My butt only accepts butter.” Undeterred, Mr. Julio heads downstairs, where he greets the sight of a nude Siri lying face down on the sofa with the ominous phrase “A man has got to fuck what a man has got to fuck.” Faced with the threat of rape by his employer, Siri flees to the upstairs bathroom, where, cornered and frantic to escape, he flushes himself down the toilet. When Mr. Julio finally kicks in the door, he is just in time to see Siri’s last extremity, a hand, rattling down into the bowl, following Siri to freedom.

Liberation by way of the sewer: an apt metaphor for the Cinema da Boca do Lixo, which takes its designation from a colloquial name—“Boca do Lixo” translates as “Mouth of Garbage”—for the slice of the Santa Ifigênia neighborhood in São Paulo in the area of Rua do Triunfo’s intersection with Rua Vitória near the city’s central railway terminus, the Luz station. The neighborhood became a haven for foreign film distributors in the 1920s and ‘30s, with Fox, Paramount, and Metro renting warehouses in the vicinity. Rio de Janeiro was then still the center of Brazil’s federal government and leading film production center, home of film studio Atlântida Cinematográfica among others, but booming, bumptious São Paulo had the superior railway infrastructure, and distributors were drawn there by the proximity of the train lines and the access they supplied to the vast inland state.

By the mid-‘50s the Boca, a seedy district to begin with, had become a wide-open red-light district; when local government cracked down on flesh-peddling in Bom Retiro—the former center of such activities in São Paulo, run by Jewish gangs—the action moved to the Quadrilátero do Pecado, bounded by the avenues and streets Duque de Caxias, Protestantes, São João, and Timbiras. Thanks to the nearby terminal, cheap hot-sheet hotels abounded, and with the booming business came the pimps, bandits, cut-purses, and black-marketeers who would malinger on Andradas, Aurora, Timbiras, and Vitória streets. Hiroito de Moraes Joanides, for a time the reigning O Rei da Boca do Lixo, made a killing in the streets on girls, cocaine, and methamphetamine. His father was an admirer of the Japanese emperor, hence the name, but Hiroito was suspected to be no admirer of his father, accused and acquitted of parricide after the old man’s fatal stabbing—the only one in a long list of crimes he denied responsibility for until his dying day, diligently cataloguing the rest in his 1977 autobiography Boca do Lixo, having turned man of letters after his arrest for murder in 1962.

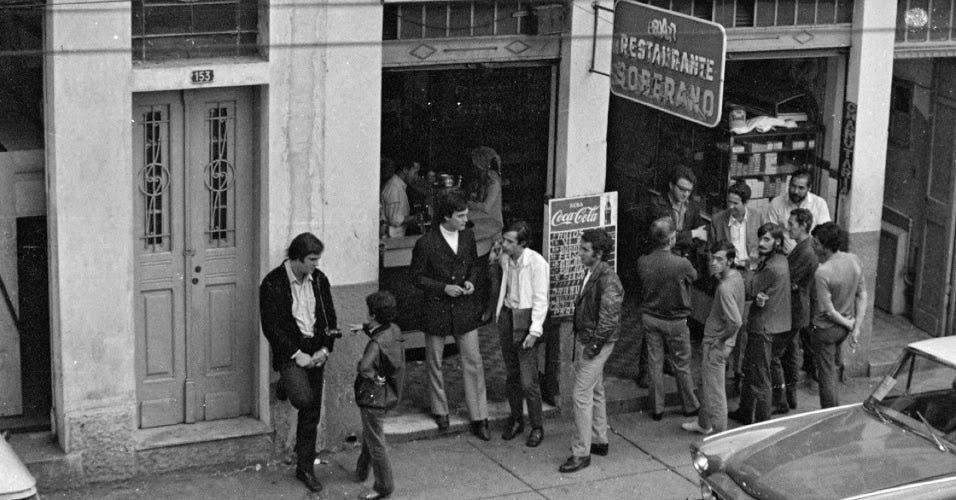

Around the same time Hirohito’s reign was coming to an end, the Boca was becoming the center of a new and more disreputable kind of domestic filmmaking community made up of newcomers and refugees from the collapse of Maristela, Multifilms, and Vera Cruz, the Brazilian studios of the 1950s, a community very often operating outside the auspices of the commercial mainstream but reliant as the majors had been on the nearby railways to ship the goods to market. (That frequenting the area in the periphery of train stations invariably brings one closer to the working-class and shirking-class life of a city is a phenomenon I’ve discussed in a previous piece on the German Bahnhofskino.) The symbolic center of this industry—which in fact consisted of businesses scattered all over downtown São Paulo—was the three-and-a-half block stretch of the Rua do Triunfo, dotted with distributors large and small, equipment rental and repair companies, and, at No. 155, the bar-restaurant Soberano, a meeting place for filmmakers, technicians, actors, and hustling film students, a sort-of Brown Derby of the Boca do Lixo. As early as 1949 producer Oswaldo Massaini had set up his Cinedistri Ltda. on Rua do Triunfo, and other would-be moguls would follow in his wake. And so it happened that once upon a time in the Boca the garotas de programa (“program girls,” a genteel phrase for a call-girl) and the penny-ante gangsters and the movie people and other assorted adventurers came to live and drink and try to turn a few real side-by-side. According to Ozualdo Ribiero Candeias, a legendary figure of the Cinema da Boca do Lixo, an unspoken truce existed between the thieves and the showfolk: “Nobody messed with us.”

Garret, a native of the Portuguese Azores archipelago born José Antônio Nunes e Silva, came to Brazil to stay around 1966, when still in his late teens, and his life in Brazil—he died in 1996, by some reports disillusioned and depressed that the industry that had provided him his livelihood has disappeared—roughly corresponds to the rise and fall of the Cinema da Boca do Lixo. The bastard filmmaking ethos of Cinema da Boca do Lixo—to call it a “genre” or “style” doesn’t quite cover something so amorphous—has no exact birthdate, but 1967 is an important year, for it was the year of A Margem (The Margin), the debut feature from Candeias, an autodidact farmer’s son and former truck driver, civil servant, and furniture polisher who’d turned out his first 16mm short in 1955, learning by doing.

This significantly titled production was a shoestring affair offering a slice of life as lived among the poor who inhabit the muddy banks of São Paulo’s Tietê River, at its center two stories of unrequited passion: that of a black prostitute for a tight-lipped, arrogant loafer without job or prospects, and that of a slightly cracked beggar for an office girl who moonlights in a brothel. Stylistically bifurcated, the first half of A Margem lays out and explores a radical aesthetic premise, shooting entirely through the subjective perspective of one character or another—the same approach taken years later by that greatest of English sitcoms, Peep Show, with shifts of perspective obeying emotional and aesthetic considerations rather than merely keeping up with who’s talking, talking being very scarce in Candeias’s film. (The filmmaker was drawing and expanding on the perspectival experimentations in the previous year’s O Corpo Ardente by Walter Hugo Khouri, another frequent Boca do Lixo habitué, and a sort of bridge figure between the Cinema Novo intellectuals and the Boca primitives.) What begins as a woman’s ambling pursuit of a reticent lover transforms with the dawning of propriety, responsibility, and tenderness, before the movie mutates again with the first sudden, savage incursion of death. The things that Candeias does with point-of-view and use of foreground space are continually surprising, and the film as a whole is a work of extraordinary intimacy and intuition—two of the most valuable qualities that cinema can have.

A Margem would be one of the foundational texts of a “movement” sometimes referred to as cinema marginal. The term had more traction with critics than with filmmakers, used to group together a new crop of films that, while often artistically ambitious, were more willfully populist in nature than those of the highbrow Cinema Novo, which had flourished at film festivals abroad. Chief Cinema Novo theorist and filmmaker Glauber Rocha hailed from the state of Bahia, in the country’s northeast, and Cinema Novo was largely a Rio-based movement; Candeias and the Cinema da Boca do Lixo filmmakers belonged to São Paulo, the crass, commercial, and far less picturesque upstart megalopolis to the south. These were films and directors self-defining in opposition to Cinema Novo, but also set apart from Hollywood, always endeavoring to flood the Brazilian market with U.S. product, and from the high-finish output of the foundered Brazilian studios—or, often, the state-run Embrafilme, founded in 1969—due to the rough-and-ready nature of these independent, seat-of-the-pants undertakings, and their frequent commitment to working-class and bas-fond subjects. And this loose confederation of filmmakers found a home in the Boca do Lixo, where João Callegaro and Carlos Reichenbach set up their Xanadu Productions to make the omnibus film As libertinas, and where 21-year-old Rogério Sganzerla picked up scenes for his O Bandido da Luz Vermelha (The Red Light Bandit; both 1968).

A marginal cinema, yes, but also an underground cinema—the Cinema da Boca do Lixo has sometimes been called “udigrudi” cinema, udigrundi being a corruption of the English “underground” coined, pejoratively, by Rocha. (By the late 1960s the Cinema Novo that Rocha had prophesied and proselytized for had lost its initial velocity, and well before Rocha began to loudly praise the military junta of Ernesto Beckmann Geisel in the mid-‘70s, many Brazilin cineastes had come to regard the Cinema Novo as an establishment to be bucked, not a vanguard to be followed.) And the underground was quite literally the territory of another artist often associated with the Cinema da Boca do Lixo, José Mojica Marins: his on-screen alter-ego, Zé do Caixão, or Coffin Joe, was an undertaker who, when not preparing the dead for burial, busied himself scouring village streets, striking terror into townsfolk, and searching for a woman worthy to bear him a son.

For Marins, as for Candeias—who’d done uncredited work on the script of Marins’s 1963 Meu Destino em Tuas Mãos (My Destiny in Your Hands)—making films in Brazil in the mid-‘60s was practically a matter of working in a vacuum, managed through a pot-luck production method described by Marins in a 2005 interview: “My way of financing my film is in the form of cooperative. I was the pioneer in using the system of coop to produce films. After the collapses of Vera Cruz, Maristela and Multifilms it seemed that it was the end of Brazilian cinema. There was no way to produce more films. It went that way until the government began to fund cinema productions. That was the moment that the independent filmmakers began to appear. Sganzerla, Candeias, Reichenbach, all used the system of cooperative.”

Quite literally, Marins had been raised in the cinema: his father managed a movie theater in São Paulo’s Vila Anastácio, and he claimed to have gained his sense of vocation from viewing there an educational short about venereal disease. As with many a Boca do Lixo showman, he was proudly self-taught, telling an interviewer “I never read a book about cinema. It all comes from my head; any book would impede me. I did not want to make normal cinema. I broke rules, like the axis rule, with my technique. And I hate those technical gadgets like the image assist. I just tell them: Take the camera and a 25 objective lens. No, a 14. I don’t even need to look.”

Marins had introduced his Zé do Caixão, cutting a striking figure with his black beard, cloak and top hat, and his rake-like, curling fingernails, in his first horror effort, 1964’s À Meia-Noite Levarei Sua Alma (At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul). He was a gifted guignol entertainer with a relentless, punitive approach in the editing room and an innate rapport with his public—a largely Roman Catholic public with a deep-seated belief in Evil—sealed by his penchant for direct-to-camera addresses. There was something for everyone in Marins’s tale of a self-styled Sadean atheistic Übermensch who publicly eats leg of lamb with relish on Holy Friday and on a whim maims the scuttling, superstitious peasants who surround him with impunity: the vicarious thrill of total revolt against all forces of authority, as Zé do Caixão denounced the hypocrisy and timidity of society; the reassuring stroke of divine spiritual retribution to bring the reign of terror to an end, however temporarily. Antihero Zé do Caixão made a sensation, launching a comic book empire in addition to a film franchise, and a few years later when Volkswagon released the VW 1600 on the Brazilian market, the boxy four-door—a rarity in the country at the time—was nicknamed, for its supposed resemblance to a casket, the Zé do Caixão.

Marins would be an essential part of the future Jean Garret’s introduction to the world of cinema—in the image above Garret can be seen, kneeling, blonde and boyish, with other graduates of Coffin Joe’s “academy,” an abandoned synagogue in Brás where Marins trained actors and technicians, and shot portions of À Meia-Noite Levarei Sua Alma and the second Zé do Caixão film, 1967’s Esta Noite Encarnarei no Teu Cadáver (This Night I’ll Possess Your Corpse). The young Portuguese, after supporting himself for a time as a bookseller, had by 1967 adopted the pseudonym Jean Silva, and begun working as an advertiser and photographer, producing photonovelas—comic book-style stories using sequential photographs accompanied by dialogue bubbles—to be published in the youth magazine Melodias. On the shoot for 1968’s Trilogia do Terror, a horror anthology on which Marins directed one of the segments, Garret worked as a scene photographer, stage manager and, in the Marins episode Pesedelo Macabro (Macabre Nightmare), as an actor. Some sources take the association back still further, listing Garret as the assistant director on Esta Noite Encarnarei no Teu Cadáver. Whatever the case, through Marins, Garret had come to the Boca, and in the Boca he stayed.

Garret continued to act—for Marins again, in his 1968 antholoy film O Estranho Mundo de Zé do Caixão, and also for Candeias, who’d directed another of the Trilogia do Terror segments—and also to work as a set photographer, serving in that capacity on 1974’s Adultério, as Regras do Jogo by Ody Fraga, another towering figure of the Cinema da Boca do Lixo. Fraga, a native of Florianópolis nearly a decade Garret’s senior, had been working as a scriptwriter since 1960, and had co-directed his first feature with Armando de Miranda in 1966, O Diabo de Vila Velha, a “Western” set in the sertão (“hinterlands”) of northeast Brazil—the sertão film was at that time a commercially proven genre—with a script by Fraga and Marins. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s, however, that Fraga began to work steadily as a director: more than steadily, in fact, beginning a streak of sudden, startling prolificity.

This was a period in which the Brazilian film industry as a whole was working overtime to satisfy a new demand for product, a demand driven by a number of factors. In 1971, twenty-eight million tickets were sold in Brazil for Brazilian movies, about 15% of the total, a percentage kept down thanks to the MPAA’s quest for Hollywood hegemony. In 1978, the number was sixty-one million. Part of this may have had to do with new resources being pumped into Embrafilme, by the middle of the decade under the steady-handed management of Roberto Farias, with the result of improved local product that could compete with on level footing with foreign films—in 1976 ten million Brazilians watched Sônia Braga in Bruno Barreto’s Dona Flor e Seus Dois Maridos (Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands), making it the most financially successful film in Brazilian history. Part of it, also, was the lei da obrigatoriedade, or “Obligatory Law,” a law instituted by the authoritarian Brazilian military government that had ruled the country since spring of 1964 and enforced by Embrafilme and the Conselho Nacional do Cinema (CONCINE). The lei da obrigatoriedade made it mandatory that cinemas screen Brazilian movies for certain number of days of the year. In 1969, the bar was set at 63 days, and it would inch up over the decade to come. In 1976, this number climbed from 84 days to 112. In 1978, the quota increased again, to 133. In 1979, it hit a ceiling of 140 days a year.

The ‘70s were a boom period for Brazilian cinema, and they were the heyday of the pornochanchada—the term is a portmanteau, combining “porno,” which should need no introduction, and chanchada, a musical comedy genre that dominated the Brazilian box-office in the 1930s and ‘40s, when they were pumped out by the Rio studios. The term pornochanchada is often treated as a synonym for “sex comedy,” and to be sure there were more than a fair share of newly liberated bombshells, chiseled studs, exasperated cuckolds, nosey old ladies, repressed clergymen, sweaty-browed perverts, and all the rest to be found on Brazilian screens during the peak years of the genre. A frequently cited inspiration for the pornochanchada was the commedia all’italiana cycle of the 1960s and ‘70s, which played to enthusiastic crowds in São Paulo, a place whose enormous population of oriundi (descendants of Italians)—about half of the state—amounts to more Italians than can be found in any city in Italy. Garret’s studies in sexual pathology like 1975’s Amadas e Violentadas (Beloved and Raped) and 1979’s A Mulher Que Inventou o Amor (The Woman Who Invented Love) are rather closer in affinity to the Italian giallo thrillers of the period, however, and one risks missing a great deal in writing off the pornochanchada as mere horned-up frivolity.

The cynical read on the pornochanchada phenomenon suggests that the military government was only too happy to let brainless beachside sex romps proliferate, serving as T & A bread and circuses for a horny and therefore distracted public, though critic Inácio Araújo, in his essay accompanying the 2012 IFFR program, finds an anti-authoritarian underpinning to early taboo-busters like Sganzerla’s O Bandido da Luz Vermelha and A Mulher de Todos (1969), which helped to pave the way for an explosion of erotic cinema in the decade ahead: “This was the time for young people to celebrate the work of Marcuse, Norman Brown, beatniks and surrealists. In short, the ideal of personal liberation associated to political liberation, mostly deriving from May, 1968 in Paris, was beginning to set itself in this conservative environment.”

In any case, the pornochanchada spread like clap through the Boca do Lixo. Massaini, the Boca pioneer who’d tasted prestige when Anselmo Duarte’s Cinidistri-produced O Pagador de Promessas (The Given Word) won the Palme d’or at Cannes in 1962, in the 1970s went in for pornochanchada, with Cinidistri money backing Anibal Massaini Neto and Olivier Perry’s A Infidelidade ao Alcance de Todos (1972), Victor Lima’s Tem Folga na Direção (1976), and José Miziara’s Embalos Alucinantes (1978). Even Marins got in on the action, with 1976’s Como Consolar Viúvas (How to Console Widows), directed under the pseudonym J. Avelar. The pornochanchada begat its own stars, most of them women, and scouts scoured the country for new beauties: Helena Ramos, Zaira Bueno, Nicole Puzzi, “Muse of pornochanchada” Aldine Müller, Matilde Mastrangi, Helena Ramos, Zilda Mayo, Arlete Moreira and her sister Claudette Joubert—both of whom would work with Garrett—and Miss Brasil 1969, Vera Fischer. The wide-open sexual marketplace of Quadrilátero do Pecado found its equivalent operating under the cover of legitimate entertainment on the Rua do Triunfo, as oftentimes parts were decided through testes de sofá (sofa tests), which are exactly what they sound like. Marins, whose ill-starred O Despertar da Besta (Awakening of the Beast) contains a particularly grueling testes de sofá scene, remembers “a mother taking her virgin daughter to get a role in erotic films”; Fischer claimed she escaped the worst by feigning a particularly bloody menstruation; Müller, who went on to success on telenovelas for the enormous television network Rede Globo, recalls bringing her son to work, and thereby generating sympathy and protection.

None of this is to suggest that the testes de sofá were more common in the world of Cinema da Boca do Lixo than they were elsewhere in Brazilian film and television—there is a significant amount of anecdotal evidence to suggest that this is not the case—but to be realistic about the circumstances under which the industry operated, and to some degree operates still. Earlier this year, David Cardoso, Jr., son of the greatest of male pornochanchada stars, claimed his career had been stymied for refusing testes de sofá at Globo.

Cardoso Sr. had arrived in São Paulo from the Mato Grosso do Sul, found work as an actor after starting out as a technician for comic performer Amácio Mazzaropi’s Pam Filmes, shot to celebrity after his starring role in Glauco Mikro Laurelli’s A Moreninha (1970), and three years later was in a position to found his own production company, Dacar Produções Cinematográficas. It was Cardoso who offered Garret his first writer-director gigs, both released in 1975, A Ilha do Desejo and Amades e Violentadas, the latter a more-than-worthy entry in the serial killer-in-love microgenre that includes Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) and Claude Chabrol’s Le boucher (1970).

In Amades e Violentadas, Leandro (Cardoso, uncharacteristically bearded and bespectacled) is a successful author of crime stories who lifts his premises from memories of the murders that he’s seen committing in flashes of uncontrollable rage—whenever intimacy with a woman threatens to lead to consummation he’s stricken by childhood flashbacks to his father’s sexual humiliation and eventual revenge, and soon after death follows for his would-be lover. A chance for redemption comes into view when erstwhile hunter Leandro has the chance to turn protector, beginning a chaste romance with a woman (Fernanda de Jesus) who he finds fleeing from a satanic sect (!) preparing her for sacrifice, but prying eyes and a putrefying corpse in his Bluebeard’s cellar finally forestall any chance for a new beginning, a police dragnet closing in only to find that Leandro has already put a bullet in his brain rather than risk connubial catastrophe befalling his beloved.

As many a giallo, Amades e Violentadas is the kind of volatile concoction born of the sexual anxieties resultant when, in a deeply Catholic country, a swinging new morality meets the staid old morality, and when those anxieties are observed and distilled into genre form by an astute artist. The masculine neuroses of Amades e Violentadas find a feminine rejoinder in A Mulher Que Inventou o Amor, a superb vehicle for Müller, in a part that both acknowledges and subverts her role as a blank slate upon which male fantasy can be projected, and reveals her talent for mesmerizing opacity. (Müller would later star in what is often described as Garret’s most personal film, 1980’s O Fotógrafo, made for his own production company, Íris Produções Cinematográficas.)

The film opens as Doralice (Müller), a naïve bumpkin, is cornered and deflowered in the meat locker of a butcher’s shop by its porcine proprietor, who sends her home with some filet for her trouble. Doralice fears that her prospects for marriage are gone with her maidenhead, but her roommate, who spends her weekends working as a garota de programa, explains the ropes of the profession, and very soon Doralice has graduated to being the kept woman of a cultured old doctor, an impotent erotic connoisseur who’s like a low-rent version of Alain Cuny in Emmanuelle (1974) who lectures her on opera and generally Eliza Doolittles her into the new identity of “Tallulah,” a woman of grace and refinement. Whether as Doralice or Tallulah, our heroine experiences no pleasure in bed, only learning to placate the egos of the men she sleeps with through a theatrical performance of moaned ecstasy. The real thing is reserved for her ritualistic masturbation sessions, performed in a wedding dress bought with prostitution proceeds, before the image of telenovela star César Augusto (Zecarlos de Andrade), who she seduces in the course of a round of role-reversal games—paying a motorcyclist for sex, picking up a young gay man at the park while in masculine drag—that allow her for the first time to find pleasure with another in bed.

From first neon-splashed trauma to blood-and-roses finale A Mulher Que Inventou o Amor is invested with a chill beauty by cinematographer Reichenbach, a Boca do Lixo utility player who in addition to directing his own films worked on those of others in just about every capacity imaginable. Reichenbach also shot Garret’s forebodingly gorgeous, Fraga co-scripted Excitação (1976), a horror-thriller in the vein of Polanski’s Apartment Trilogy set largely in and around an isolated moderne beach house that’s the scene of a fraught love quadrangle. Garret loved impeccably decorated interiors shot like specimen cases under glass and strategically deployed splashes of color (eye-searing reds are a particular favorite), and his soundtracks always swing, though he took some flak for his reliance on classical cues, as though such things should only be the provenance of highbrow swells. A stylist with a graphic designer’s eye for immediate visual impact—it turns out the photonovelas were a good school for teaching the mysteries of mise-en-scène—Garret had an especial affinity for damaged psychologies and an understanding of the fantasy lives of his countrymen, as well as a keen comprehension of the degree to which those fantasies were shaped by the culture industry that he served. All of these factors came together in this popular artist-entertainer pushing the boundaries of so-called pornochanchada, a genre whose days were numbered when certain other boundaries began to fall.

While there was a great deal of leeway allowing for bared bosoms and even sadistic violence of the sort meted out by Zé do Caixão, censorship was very much a factor under the military government that allowed for the flourishing of Cinema da Boca do Lixo, and the rules under which it was enforced were ever-changing and unpredictable. Marins himself faced the censor board’s ukase with his O Despertar da Besta, completed in 1969, though its psychedelic climax was not to melt minds in Brazilian cinemas until 1983, the film a scourging indictment of a corrupt society awash in and dependent on drugs and sick sex, featuring Marins stepping out from behind the cover of Zé do Caixão to defend himself in a trial-by-television-panel. João Silvério Trevisan, the screenwriter of A Mulher Que Inventou o Amor, a prominent gay rights activist and one of the most highly regarded novelists and essayists of his generation, turned to literature when his career as a director was scuppered, his kamikaze first feature, 1970’s Orgia ou O Homem que Deu Cria (Orgy [Or: The Man Who Gave Birth]) hidden from view immediately. Sganzerla, whose short-lived, clandestine production company Bel-Air Films, formed in 1970 with Júlio Bressane in Rio de Janeiro, was conceived in opposition to the government and operated without the blessing of the censorship board, spent most of the decade to come in exile.

Hardcore sex on screen, held at bay for some years by the military government, came late to Brazil, but it came with a vengeance when it was discovered that there was big money in money shots. Reichenbach’s 1981 Anarquia Sexual (Sensual Anarchy) was the first Brazilian film to be released with a new designation from the then-recently-formed Conselho Superior de Censura (Superior Council of Censorship): “espetáculo pornográfico,” or “pornographic spectacle.” The film’s alternate title, O império do desejo (The Empire of Desire), denotes a debt to Nagisa Ōshima, whose 1976 In the Realm of the Senses had been a massive hit in São Paulo when it finally opened in the city’s art houses in ’79. Along with Italian imports, the Japanese cinema made an indelible impression on certain of the Boca do Lixo directors; Reichenbach, one of the more cinephiliac of the bunch and a dynamo deserving of more space than I give him here, was for example a habitué of the cinemas in São Paulo’s Japanese-majority Liberdade neighborhood. I don’t know if Shohei Imamura’s films ever got much play in the Liberdade cinemas, but Imamura’s description of his principle subjects—the lower half of the human body and the lower half of the social structure—could certainly be applied to much of the Cinema da Boca do Lixo.

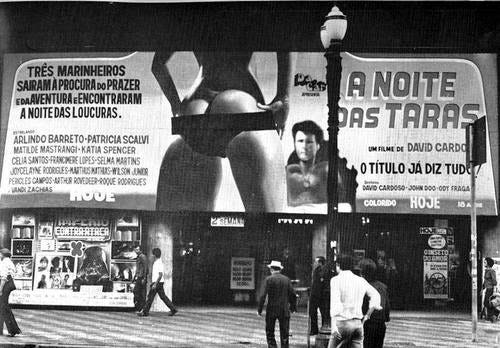

With Laente Calicchio and Raffaele Rossi’s 1981 Coisas Eróticas, Brazilian hardcore had its Deep Throat (1972), its crossover sensation, seen by nearly five million Brazilians. Italian émigré Rossi, a millionaire for a moment thanks to this coup, blew most of his profits on a short-lived indoor soccer team, Grêmio Recreativo Rossi, but he had shown others the way to fortune, and they followed. By 1984, 69 of 104 Brazilian films shown in São Paulo were pornographic, and the more polished and pricey sort of pornochanchadas had breathed their last.

The 1980s, marked by the hardcore invasion and a precipitous drop in ticket sales accompanying a period of broader economic stagnation in Brazil and the appearance of the VCR, were the last gasp days of Cinema da Boca do Lixo. Some of the films of these years seemed to embarrass even their slumming authors, though I confess to a sweet spot to them, the best of which display the creative ferment that marks any period of decline and decadence, a genuinely grimy lowlife élan, and a sense of total erotic abandon. I have seen enough at this point to be familiar with the particulars of fellatio as it was performed in São Paulo at the beginning of the 1980s—languorous and breathy, with a great deal of twirling tongue action—and to wonder if sex is one of those things, like regional accents and guitar tone, that has finally been standardized by the all-over imposition of mass culture.

A particular favorite filmmaker of this period is the maniacal Sady Baby, born Sady Plauth, whose films evoke a world of nihilism, wanton violence, and total libertinage—at least insofar as I can tell, never having seen one subtitled. No taboo goes unshattered, including bestiality, as suggested by the title of one of Sady’s first films, 1984’s Emoções Sexuais de Um Cavalo (Sexual Feelings of a Horse) (Sady Baby, from a 2013 interview: “I put a lot of myself into that movie.”)

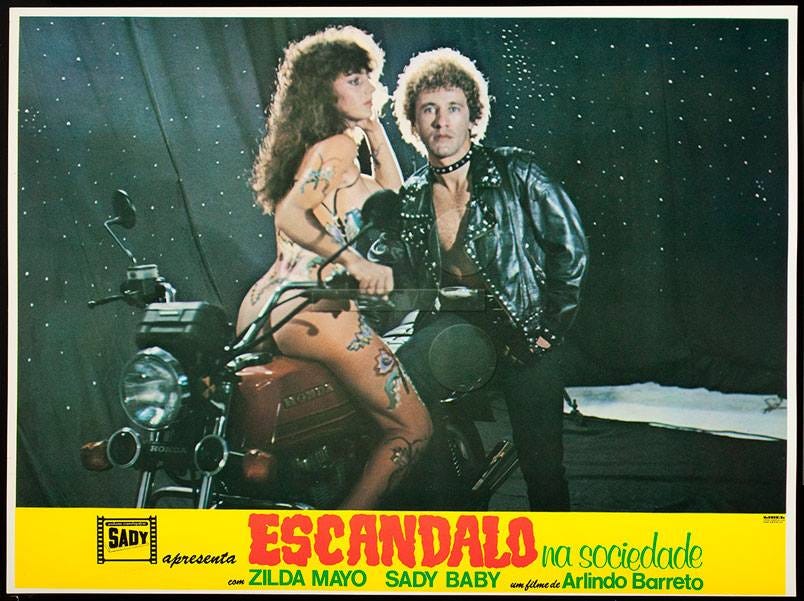

First seen as an actor in Arlindo Barreta’s 1983 O Escândalo na Sociedade, Sady appears in nearly all of his own films, a compactly built punk satyr with a luxurious halo of curls and a deviant Droogish chortle, his brutal, smirking screen persona taking the antiheroism of Zé do Caixão to its amoral apex. In 1983’s Meninas, Virgens e P... (Troca de Óleo), he’s a fresh-out-of-prison menace to society, shirtless under a black leather jacket, metal-studded like his blue jeans, and wearing fingerless leather gloves with four-inch nails protruding from the knuckles; retrieving wads of real hidden in 35mm canisters before heading off to wreak havoc, he looks cooler than any film director ever has before or since. The Sady Baby character is not, however, without a sense of justice: at the outset of 1985’s No Calor do Buraco, Sady interrupts an attempted rape on a muddy river bank—Sady, whose films are quite literally filthy, never misses an opportunity to shoot people flailing in murk and mire—ties up the would-be rapist, watches while his intended victim teases him to arousal, then guffaws uproariously when the assailant’s suddenly tumescent member tugs a tripwire attached to the trigger of a rigged-up rifle that blows the scumbag away.

The soundtracks to Sady Baby’s films, compiled without a single thought to rights clearance, are simply insane: a brief stretch of Meninas, Virgens e P... (Troca de Óleo) gives us the Monkees’s “I’m a Believer,” ABBA’s “I Have a Dream” and, over a scene of male-on-male sodomy, Wham!’s “I’m Your Man.” (Gay sex is less frequent than the heterosexual variety in Sady Baby’s films, but not much less.) An air of menacing lasciviousness hangs over everything, and what there is of plot takes a back seat to extended scenes of sloppy, bibulous, Boschian orgies that have the character of a mosh pit: liquor bottles being glugged down or dumped out, crotches being fondled, and men with drug-glazed faces numbly submitting to blowjobs. Just about everyone fucks and sucks on-screen, except for Sady—this mirrors Jean-Luc Godard’s complaint about Truffaut’s La Nuit américaine (1973)—who employs a stunt cock. Along with Sady Baby, a ragtag repertory company of depraved perverts travels from film to film, their number including a disconcertingly beautiful actress credited as Leyk-Dú and a comic relief old fart called “Bim Bim,” who can be seen with little Chumbinho in his swansong, José Adalto Cardoso’s arrestingly idiotic 1987 As Taras de Um Minivampiro (The Taint of the Minivampire; in this fine film, Bim Bim plays a provincial mayor who hopes that the appearance of a vampire in his town will act as a lure to American tourists, notwithstanding the fact that the creature has blunted fangs, is the size of a Kindergartener, and can only extract blood by sucking on the used sanitary pads of menstruating women.)

What little information I’ve been able to glean about Sady Baby, the man, comes from the profile quoted above by Matias Rech de Lucena, which includes a remarkable personal recollection: “When I was around seven, I used to go to Balneario Camboriu in Santa Catarina for summer vacations with my family. Every day, at the edge of the beach, a guy with curly blond hair, a Viking hat, and a G-string thong would get on a megaphone and announce the beginning of an erotic play called Soltando a Franga, which, loosely translated, means ‘Release the Inhibitions.’ Years later I realized that the strange man hosting sexy public theater on the beach was Sady Baby himself.” De Lucena catches up with Sady Baby at the Caxias do Sul Penitentiary, where he had been doing time since being collared during a routine traffic stop in February of 2013. He had then been missing for five years, rumored to have committed suicide by throwing himself off of a bridge into the Uruguay River, wanted by the police for hiring a minor to play his daughter in a (presumably pornographic) film titled, of all things, The Director’s Daughter. Sady chalks it up to a big misunderstanding, in between nonchalantly mentioning his forty children, his hijinks on an “orgy bus” with which he and compatriots traveled Brazil in the ‘90s, and his Catholic faith.

The pornochanchada directors, no less than newcomers like Sady Baby, followed the money to hardcore during an industrywide crisis. The final Ody Fraga film released during its maker’s life, the Chumbinho-starring 1985’s Senta no meu, que eu entro na tua (Sit On Mine and I Will Enter Yours), was a magic realist diptych: in the first episode, a woman’s vagina gains the ability to speak and a mind of its own; in the second, a man receives the dubious gift of a second cock sprouting from his scalp. Garret’s hardcore outings were as idiosyncratic as his pornochachada, and notwithstanding the fact that O Beijo da Mulher Piranha (Kiss of the Piranha Woman—the title references Héctor Babenco’s prestige hit of the previous year, and the Manuel Puig novel on which it was based) features a scene of a woman blissfully receiving cunnilingus from a tame piranha in her bathtub, Fuk Fuk à Brasileira is unquestionably the wildest.

Shoestring ingenuity is on display from the first seconds of Fuk Fuk à Brasileira: in the opening credits, white lettering on what appear to be overhead projector transparencies are overlaid onto collages of pornographic images or live female anatomy. The title appears between two burning cock-shaped candles, obscured occasionally by a bobbing dildo. The screenplay is credited to one “J.A. Improviso,” a joke that probably doesn’t need translation, and says all there is to say about the air of throw-shit-to-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks invention that prevailed on these “sets”—mostly shabby hotels, lower middle-class hovels, and dodgy drinking establishments. (Sady Baby’s films return to a graffiti’d romper room that palpably reeks of spilled cachaça, testicle sweat, and desperation.) After his deliverance from buggery via self-flushing, Siri sneaks back into his bourgeoise employer’s home where he loads his collection of gifted dildos into a Styrofoam cooler and hits the road, making friends with an acquiescent landlady, a young twink avoiding a gay-bashing from a grunting macho at the beach, and an illiterate hick with a talking horse, all thanks to his load of rubber dongs, which he sells door-to-door after labeling his cooler as a “PORNO-SHOP AMBULANTE.” Then, quite abruptly, to the strains of “Also sprach Zarathustra,” Siri explains that he has been contacted by a spaceship from Uranus, its non-arrival announced by several false-alarm crackles of fireworks: “The special effects department screwed up,” Siri apologizes, “You know how Brazilian cinema is.”

Eventually the craft, predictably shaped like a giant schlong, does appear and puts Siri to work teaching it the local erotic vernacular before showering him with milky gouts of “space sperm.” In a final monologue, Siri, ever the crafty hustler, describes how his new business of selling the jizz to people with sexual dysfunctions has made him a mint, after which the frame pulls back to reveal him surrounded by copulating couples while sitting regally on a toilet: once a flushed flunky, now King Shit. It all makes for a pleasingly puerile ride, one not without something to say about an existence of scraping to get by without resources, in cinema or in life; as Siri observes: “Finding a job?… What’s left in the in the third world for a black illiterate dwarf who can’t talk and hates work?” And soon enough, even the last hangers-on on the Rua do Triunfo would need to freshen up their resumes.

It is possible that Garret, who found work in the “legitimate theater” at the Teatro Bibi Ferreira, didn’t share my high estimation of his hardcore efforts, for he directed them under a new pseudonym, J.A. Nunes—similar precautions were taken by several Cinema da Boca do Lixo filmmakers who’d come up through the 1960s and ‘70s and who now found themselves working in hardcore. Marins, for his part, didn’t hide his role in such productions as 1985’s zoophilia-featuring 24 Horas de Sexo Ardente [24 Hours of Explicit Sex], boasting to a reporter in 2004 that “Only I had the courage to keep my real name in the credits.” (In fact, Fraga did as well.)

At any rate, the indignity was not to last for long, as the Brazilian film industry was headed for a near extinction-level catastrophe. Audiences had been dwindling steadily since the quota system reached its high watermark in ’79, and movie theaters, echoing an international trend, were shuttering en masse—there had been some three thousand in Brazil in 1975; a decade later, the number was about half of that. Some blamed the quota system, which made no provision to offset losses faced by exhibitors, and exhibitors specializing in foreign imports posed legal challenges to the lei da obrigatoriedade. The military government, after twenty-one years, ended with José Sarney’s victory in a direct election for president. Federal meddling in the field of cultural production, be it through the state-owned Embrafilme or the lei da obrigatoriedade, was increasingly felt to have the unwelcome odor of the old regime clinging to it, and Brazil followed the world in its fresh romance with the promises of free trade. Obligations were dropped, Embrafilme dissolved, and with the particular circumstances—cultural, financial, and political—that had allowed for the flourishing of the Cinema da Boca do Lixo no longer existing, so, too, did the Cinema da Boca do Lixo pass from this earth. The Americans came, not to see Minivampires, but to fill the remaining cinemas with their blockbusters. Santa Ifigênia, and the Boca do Lixo, became the center of a new industry, the crack-cocaine trade, part of São Paulo’s Cracolândia, the area next to the Luz station an open-air drug market.

Garret, as director Alfredo Sternheim observed in his essay for the Rotterdam retrospective, was one of a few dispirited Cinema da Boca do Lixo luminaries to pass away before their time: Cinematographer and director Osvaldo de Oliveira died in 1990, aged 59. Tony Vieira, an actor and director who’d followed the familiar pornochanchada to pseudonymous hardcore route, passed the same year, only 52. Reichenbach lived to see his work celebrated at Rotterdam, and died only months after. Marins, at least, survived to this year, and to see the continuing reappraisal of Cinema da Boca do Lixo; in his documentary contribution to the 2015 anthology film Memórias da Boca, he can be seen strolling the Rua do Triunfo, and recalling what once was. He was not alone in preferring the company of ghosts; in an interview given this year, Garret’s onetime champion, the now 77-year-old Cardoso said “I live a lot in the past. When I walk down Avenida São João, in São Paulo, and remember that there were eleven street cinemas there, it makes me very sad. I stay at my place in the Pantanal, watching old movies and getting emotional. I drink a lot… I drink like a skunk, every night.”

The Cinema da Boca do Lixo is gone, but through its films we can still see something of the past where Cardoso spends his sodden nights on the Pantanal, the tropical wetlands which are, as I write, being blackened by wildfires. Which brings us back to the endangered Cinemateca Brasileira, that institution which has been so vital to conserving the legacy of the Cinema da Boca do Lixo, even at its most scandalous—in addition to Fuk Fuk à Brasileira, they struck a print of Senta no meu, que eu entro na tua for Rotterdam—and which now finds its very existence threatened by a hostile government.

The story, in brief: After years of struggling to staunch the bleeding of successive budget cuts, the Cinemateca was faced with a decisive crisis following the election of Brazil’s current president, Jair Bolsonaro. Former president Dilma Rousseff, in 2013, had drained the resources of the nonprofit in charge of the Cinemateca, and the institution was subsequently run by a private foundation, Associação de Comunicação Educativa Roquette Pinto (ACERP). Per a timeline assembled by Rafael de Luna, in September, 2019, several contractually protected Cinemateca employees were shifted to federal positions, while “the press publicized that the new administration was using the Cinemateca Brasileira to hand out jobs to political allies and propagate the government’s extreme-right ideology, with initiatives such as a program of military films.” In December, the government revoked the contract with ACERP, and made no further provisions for the Cinemateca’s funding; by May of the following year, the reduced staff were no longer being paid, nor was the electricity bill. Tensions rose through the summer between ACERP, the striking Cinemateca workers, and the Bolsonaro government, which has made erratic and legally dubious gestures towards running the Cinemateca itself, while seeming only too happy to see the institution starved of resources and its collections endangered until a regime change is sorted out. (At the same time, the federal government has been menacing the Cinemateca Capitólio in Porto Alegre with the possibility of privatization.) On August 12, the forty-one employees of Cinemateca Brasileira were dismissed, with no plans for a transfer of institutional knowledge between administrations, no new administration announced, and not a single member of technical staff remaining to mind the collection in the interim.

In clear and present danger in this standoff is the continuing operating autonomy of the Cinemateca Brasileira, which is to say, Brazil’s history as written in moving images. There is film history in the singular, and then there are film histories in the plural. Film histories are concerned with aesthetic and moral judgements; they extol and they exclude. Film history does not—it is the sum total of everything that has happened in cinema, at least insofar as we can descry from sifting through what tattered, paltry remains have been preserved and handed down to us through archives. When Rocha, in his early publication Revisão Critica do Cinema Brasileiro (Critical Review of Brazilian Cinema), sought to elevate the reputation of Humberto Mauro, an outsider filmmaker who’d started out in the 1920s operating in the Cataguases with limited resources away from major production centers, he did so while disparaging “mechanical cinema” and a contemporary Brazilian film scene that he describes as “a disastrous alliance between immature auteurs and amateur capitalists.” (This description could be applied to much that I enjoy most in cinema, but that’s neither here nor there.) When Jairo Ferreira, onetime critic for Japanese community newspaper São Paulo Shimbum and 8mm diarist filmmaker, published his 1986 The Cinema of Invention, he limned out a canon of his own, including many of the figures discussed above: Marins, Candeias, Sganzerla, Reichenbach. In throwing a spotlight on anything, something else inevitably is left in the dark.

Spotlight value judgements are the provenance of aesthetes, critics, and artists; the archive, in its platonic ideal, stands above them. Everything is to be treated as if it were important, because our criteria for determining importance are perpetually in flux: we, poor benighted fools that we are, do not know what’s worth holding on to. I say “should” above because the reality of the situation is inevitably thornier; resources and space are limited, and decisions must constantly be made with regard to priority. It is in this tension, between an ideal of comprehensiveness and a reality of scarcity which demands value judgements, that the archive exists.

The politicization of the archive is also, to some degree, inevitable, and also an inevitability with which the archive and its keepers must struggle. For an archive represents history, and to permit history to be edited according to the needs of, say, your preferred political narrative is to permit a precedent that would allow for the other side to do the same should they get possession of the keys to the vaults.

The archive is political, and politics shape archives; that the Russian State Documentary Film & Photo Archive wound up with so many prints with German intertitles after 1945 should be proof enough of this fact. This reality was well understood once upon a time in France, where the dress rehearsal for the much-mythologized May of ’68 was l’affaire Langlois, a protest begun in February when Henri Langlois, co-founder and director of the Cinémathèque Française, was dismissed by culture minister André Malraux and replaced by a little-known film festival organizer named Pierre Barbin. Filmmakers around the world telegrammed statements asking that their films not be shown at the Cinémathèque barring Langlois’s re-appointment, and student cinephiles formed picket lines outside of the Palais de Chaillot, condemning what was derisively called the “Barbinotheque.”

Putting aside the issue of what existential threat a functionary like Barbin posed to French film culture, it’s worth asking what we might reasonably expect of a Bolsanarotheque. I’m not going to use this space to enumerate everything that’s imbecilic and odious about Bolsonaro—this information is readily and voluminously available elsewhere—but news of his government’s aggressive persecution of the Cinemateca Brasileira did recall to me one minor, if piquant, event in his impressive career of buffoonery. In March, 2019, after widespread reports that Bolsonaro had been subject to mockery at Carnaval events across Brazil, he Tweeted a video taken at a Carnival event in São Paulo, in which a man in Carnaval regalia can be seen on top of a bus shelter playing with his asshole before bending over to allow another man to piss on his head. Any normal human’s response to this would be to think, “Gee, it looks like they’re having fun, that’s great,” but Bolsanaro’s accompanying text read “I don’t feel comfortable showing it, but we have to expose the truth so the population can be aware and always set their priorities. This is what many street Carnaval groups have become in Brazil.”

I thought of this, I suppose, because there is some linkage between the anarchic Carnaval spirit and the spirit of the Cinema da Boco do Lixo—as evidence I’ll proffer the image above, of the Zé do Caixão float as it strikes fear into revelers at the 2018 Carnaval de São Paulo, one of the most beautiful things that I have ever seen. The Cinema da Boco do Lixo was a long party, one kept going, at the core, by fervid working-class energy: filmmakers in many cases originating from the working-classes, making films directed towards the working-classes. It was sometimes gross and crude and born of testes de sofá and God knows what other dirty business, but it was also, in its gross, crude, impolitic way, rudely representative of a nation that is black and white and Amerindian and straight and queer and Catholic and macho and femme and messy and motley and altogether impossible to reduce to clean-cut generalities. (This is not to try to retrospectively cast the Cinema da Boca do Lixo as “woke”—to expect the ambitions and appetites of blue-collar Brazilians in the 1970s to conform to the expectations of upper middle-class North American graduate students in the 2020s would be deranged.) The aesthetic of the Cinema da Boca do Lixo is very often mend-and-make-do, its ethos anarchic—Anarquia Sexual!—and everything about it is sure to be obnoxious to the ethic of whey-faced middle-class propriety to which Bolsonaro’s pearl-clutching Carnaval Tweet gives lip service.

You don’t have to approve of people fucking horses—I personally don’t care if they do—but you do have to admit that it’s one very effective way to épater la bourgeoisie. And in Bolsonaro’s attitude towards the Carnaval, I suspect you can see something of the attitude that the craven underlings recipient of appointments to positions of cultural influence will take towards elements of the country’s artistic history that are inconvenient to an official dogma of propriety. And make no mistake, those underlings are on the march: On September 16, Bolsonaro stooge Edianne Paulo de Abreu was appointed to run Centro Técnico Audiovisual (CTAv) in Rio, a production and conservation institution founded in 1985 through an agreement between Embrafilme and the National Film Board of Canada. De Abreau’s qualifications for such a job, beyond his association with the Partido Social Liberal, are nonexistant; in his public life, he worked as a dentist. Last week Mário Frias, Bolsonaro’s Special Secretary of Culture, gave an interview in which he stated that winners of any federal grants or fellowships for the arts henceforward would need his personal approval. Frias, who’s about as sharp as a doorknob, is a telenovela actor.

I wanted to use the pretext of the Cinemateca Brasileira’s plight to write about Cinema da Boca do Lixo because this is all dismal news that bears repeating, but also because, first and foremost, I wanted a pretext to write about Cinema da Boca do Lixo—and I hope in the future to devote more space here to several of the filmmakers mentioned herein, and to some I’ve overlooked. The operations of the Cinemateca Brasileira, it should be noted, are hardly focused on Cinema da Boca do Lixo, though I have been told that a version of the Rotterdam retro that they mounted in São Paulo, titled “The Boca in Rotterdam,” was received warmly by press and public alike, to the astonishment of the survivors of the scene still around to bask in plaudits. Per Isabel Stevens’s admirable summary of the Cinemateca’s struggles in Sight & Sound Magazine, the Cinemateca, founded in 1940, “is the oldest cinema institution in Brazil and has the largest archive in South America, with 250,000 rolls of film (including much highly flammable cellulose nitrate)… a million cinema-related documents” and some 45,000 titles in its archives, highly regarded worldwide for its photochemical processing capabilities and function as a resource for researchers and technicians.

And yet even with robust resources and the best of intentions, things go missing all the time. The prints and negative elements of Sady Baby’s films are gone, by some reports destroyed by Sady himself in an effort to avoid potential legal consequences for their contents. Hundreds of hours of José Mojica Marins on television, as host of the programs Além, Muito Além do Além (Beyond, Far Beyond the Beyond) and Um Show do Outro Mundo (The Show from the Other World), were taped over without regard for posterity, never to be seen again in this world or another. How much greater the risk, then, when resources are withheld, and intentions hostile?

It seemed proper, then, to write about the Cinema da Boca do Lixo in writing about the Cinemataca Brasiliera because, in the event of a crisis, it’s the margins that are always the most vulnerable. I don’t imagine that, come what may, every print of Rocha’s Antonio das Mortes (1969) will ever in my lifetime be in immanent danger of disappearing ; I’m not so confident in the permanence of the Fuk Fuk à Brasileiras. And “unimportant” films deserve attention, too—as the Nazarene had it, so it goes for the archive: “Inasmuch as ye have done it to the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” This is not to imply that the Cinema da Boca do Lixo is the “least” that Brazilian cinema has to offer, but to be pragmatic about the priority that’s afforded to the kind of art that I’ve been writing about here in the best of circumstances. And if the work of outlaw culture heroes of bygone times can be at risk, how much greater is the risk posed to film and video made without thought of commercial value, to Super 8 footage of a bar mitzvah in Bom Retiro in 1983, or of a supermarket opening in the Recife suburbs, or of a soccer match in Curitiba that nobody can remember the final score of, or a golden shower at the São Paulo Carnaval, or all of the inconsequential scraps entrusted to an archive that, when taken altogether, communicate something ineffable and vital about the life of a nation and its people?

In the face of a rising tide of meddlesome idiocy, it’s beyond my poor powers to contribute much of anything other than this, a mash note to Zé do Caixão and Jean Garret and Chumbinho and Bim Bim, to everything that’s morbid and misbegotten and marginal in Brazilian cinema, and to the men and women at the Cinemataca Brasiliera who have safeguarded the legacy of that cinema through the years, men and women who I have never met, but who I regard as my brothers and sisters. A mash note, and a wish for better times ahead for the Cinemateca and those who have loved it and worked for it, however unlikely such an outcome may seem at this present moment. But in a world where Sady Baby can die and come back to life, might not miracles still be possible?

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to Employee Picks, as that’s the only means I have to receive remuneration for researching and writing it. Additionally, please consider sending some money to the Cinemataca Brasiliera workers here, and signing the following petition, which has been making the rounds for some time, to save the Cinemataca Brasiliera. If I encounter additional resources, I will add them here as I do.