One of the exceptional aspects of what we refer to for the sake of convenience as Hollywood cinema is that both its trash and prestige products are, to an unusual degree, destined for export, and so much of the world has the sometimes dubious privilege of knowing it at its full breadth. I should specify that I’m not using the terms “trash” and “prestige” as value judgments, but as indications of how the marketing and publicity sectors of the film industry treat their own product: some films are to be tagged as serious artworks and handled accordingly, with an eye to awards consideration, while others are not, and these designations have little or nothing to do with underlying craftsmanship, intelligence, and feeling behind the individual works, and everything to do with a long-established hierarchy of importance. And of the films that are sorted into the trash category, a great many could be labeled as genre cinema.

While the wider world is allowed some vantage on the diversity of forms in American movies, Americans, even those of us who are more than usually hip to international cinema, very often have little comprehension of the actual, eccentric topography of other national cinematic landscapes. This can lead to a false impression of the sophistication of other traditions that could be quickly cleared up with a dose of reality. For millions and millions of French men and women, “French cinema” doesn’t just mean Godard or Pialat or Denis, if it means that at all; it means Bourvil and La Boum (1980) and Alain Chabat’s Didier (1997) and Kev Adams. One of the serene pleasures of an annual trip that I take to Flanders is the anticipation that I’ll be able to see a new poster for the latest film in the Sinterklaasfilm series, an absolutely appalling-looking holiday franchise following the adventures of the Dutch Santa Claus and his blackfaced buddy Zwarte Piet. Many Americans who profess to “love” Europe in fact only love a curated version of the continent’s most scenic spots—intact “medieval” city centers that are actually nothing of the sort but rather cleaned-up simulacra laid out by punctilious Victorians courting the Baedeker crowd. Rather than being dealt with as a heterogeneous patchwork of nations and regions with their own fraught pasts and futures, Europe is put into service by Yankee Europhiles as “Not America,” the cultivated alternative to the barbaric homeland. (The ultimate cinematic manifestation of this attitude can be found in Michael Moore’s 2015 Where to Invade Next.) Few Americans with cultural pretensions can resist getting a little starry-eyed when it comes to Europe, which is what makes all the more remarkable the accomplishment of Orson Welles’s Mr. Arkadin (1955), which gives us the Continent as a crumbling shithole full of mountebanks, chiselers, and brain-dead fashion plates.

If you are to be really interested in Europe—or any place, for that matter—you need to be interested, as Welles was, in its scurrilous underbelly, and the diverse lunacies particular to it. In short, you need to spend at least part of your time away from the cathedrals, hanging out by the train station, where people routinely get bricks thrown at them.

In Germany, there has historically been a physical connection between train travel and the seamier side of cinema, in the form of the bahnhofskino, or train station cinema. Their origin takes us back to the moment when the mutilated West Germany emerged from World War II with its grand terminuses bombed into smoldering Germania anno zero (1948) background rubble by endless B-17 sorties. Setting about rebuilding the bahnhofs, architects and planners designed a great many with a new convenience: an in-house cinema, where travelers could take in a show—Welt im Bild (World in Pictures) newsreels accompanied by commercials, short documentaries, and an animation or bit of slapstick for the kids, all running around an hour—while waiting for a connecting train.

The phenomenon was not without precedent—Union Terminal, the magnificent c. 1933 Art Deco station that’s one of the architectural highlights of my hometown of Cincinnati, was built with a 118-seat newsreel theater which for a time was operated as an art house venue, and the first newsreel cinema opened in Berlin in 1931—but nowhere to my knowledge did it occur on the same scale that it did in the postwar Federal Republic of Germany. There were bahnhofskinos in Cologne, in Dresden, in Frankfurt, in Stuttgart, in Hannover, in Düsseldorf, and beyond. Some were rather sizable; the Aki Aktualitaten Kino in Munich seated 482. They opened early, usually 9 A.M., and they closed late, around midnight. And while initially their programming was educational and family-oriented, this would be affected by the radical shift in cultural mores that came in the 1960s, and by the change wrought on West German cinema, as on cinemas abroad, with the appearance of televisions in a great many of any given nation’s homes, and with this the appearance of TV news programs like West Germany’s tagesschau (first aired 1952), which rendered newsreels obsolete.

Producers had to offer new inducements to bring in cinemagoers, and an expansion of what was permissible to depict in movies suggested what those inducements might be: sex, violence, and all varietals of extreme and transgressive material. This is the fare that the train station cinemas came to specialize in, and today—like the American “grindhouse”—the word bahnhofskino now connotes not only a type of theater but a style of cinema, one proffering illicit pleasures and cheap thrills. As with the grindhouses, most of the bahnhofskinos were on the way out by the beginning of the 1990’s, though the Aki in Nuremberg lasted until 1999, and the 272-seat Bali Kino in Kassel is still showing movies today. (Or, rather, it was until recently.)

It was in the course of watching a documentary on the bahnhofskino phenomenon, Oliver Schwehm’s 2015 Cinema Perverso: The Wonderful and Twisted World of Railroad Cinemas, that I first became aware of the existence of a prototypical bahnofskino film, 1985’s Macho Man, the second and last feature-directing outing for one Alexander Titus Benda, and a leading man vehicle for German pugilist René Weller.

Like the superstars of Schlager, Weller was a European—particularly blue-collar German—cultural phenomenon that didn’t make much of a dent in the English-speaking world. Born in a working-class family in 1953 in Pforzheim, Baden-Württemberg, Weller began training at the Blau-Weiß Pforzheim boxing gym when he was just an adolescent, and was cultivated for greatness from an early age by trainer Heinz Weishaar. The investment in the boy paid off. Weller won the German amateur featherweight championship every year from 1973 to 1976, and the German lightweight amateur title from 1977 to 1980. Compiling an amateur record of 338 wins in 355 fights, he went professional in 1981, and at the time that Macho Man was made would have been at the height of his fame. On March 9, 1984, meeting Lucio Cusma for the second time after a controversial draw in Sicily, Weller bested the Italian before a crowd of 7,500 at the Festhalle in Frankfurt am Main, winning the lightweight EBU European Championship, which he would successfully defend against Spaniard José Antonio García, Brit George Feeney (Weller detached his retina), and the Frenchmen Daniel Londas and Frederic Geoffroy.

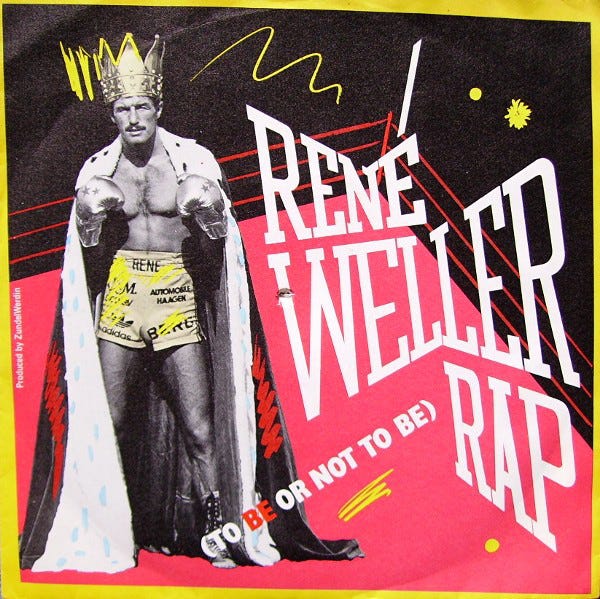

Not since George Grosz sat down to paint Max Schmeling had a German boxer been so famous. As a child, Weller had idolized Muhammad Ali, for his big mouth as much as for his fleet footwork. As a man, Weller became a busy, boisterous self-promoter, tireless in both getting his name in front of the public, and in cashing in on what name recognition he’d developed. He fed the papers choice quotes—“I am the only German man who looks better naked than dressed” is a typical bon mot—and they rewarded him with bountiful coverage. Already on the eve of his professional debut, a Bild magazine piece could propose that “Rarely has there been an athlete who has so persistently ensured that he remains in conversation.” His ambitions went beyond the ring. In the same year as the release of Macho Man, Weller released an album, René Weller Rap (To Be or Not to Be), which borrowed the beat from Mel Brooks’s “Hitler Rap,” as heard in 1984’s To Be or Not to Be. (Questionable as the taste of a non-Jewish German choosing this particular tune may be, there is no evidence of political or satirical intent in the choice.) Known for his dandyish dress, Weller would also go on to sell slacks, jackets, jewelry, and watches under the brand name “Rewell.” He was bigger than boxing, an industry unto himself.

But it is Weller the movie star with whom we are principally concerned. Macho Man stars the Beautiful René as one Danny Wagner, student of the sweet science of bruising and white knight of Nuremberg, where the movie was shot. The film opens on Weller, trained-down, toned, frothily coiffed, and handsomely mustached, cruising to victory as he pummels an opponent in a ring located in what appears to be a casino, the audible roar of the crowd in no way corresponding to the mingy visible audience. Opening titles, backed by a pulsing electronic beat courtesy Michael Landau, show Weller and his male co-star, German martial artist Peter Althof, honing their respective combat skills, while female lead Bea Fiedler is introduced dabbing down her bare breasts after getting out of the shower. The men here are to be taut and macho, the women soft and buxom, and if they’re not such great shakes as actors, well, there are always workarounds—under the instruction of Roger Fritz, director of 1970 bahnofskino classic Mädchen mit Gewalt, among other things, Weller was dubbed by Ekkehardt Belle, Althof by Hartmut Neugebauer, and Fiedler by Eva Kinsky.

Leaving his boxing gym, Danny finds Fiedler’s Sandra Petersen by the banks of the Pegnitz, beset by three hoodlums who are threatening to forcibly shoot her up with heroin—she’s helped an addict friend to get clean, it’s later explained, and thereby bitten into their smack-trafficking gang’s profit margins. Springing into action in cowboy boots, painted-on denim, and a light jacket with a voluminous fur collar, Danny makes short work of the punks without so much as mussing his bouffant, and gallantly drives the damsel in distress back to her place in Mögeldorf, making a disco date as he drops her off with light canoodling and a chaste peck on the lips.

Rangy blonde Althof’s Andreas Arnold, co-owner of a karate school, is then caught up with making a date of his own via telephone with one Lisa Roth (Jacqueline Elber), a would-be private lessons student seen wandering through a frillily over-decorated apartment that in a R.W. Fassbinder film would come off as an image of spiritually stymieing bourgeois bad taste, but here seems meant simply to connote the good life on easy street. From this point, it remains for Danny and Andreas to meet-cute, which they do through another chance encounter with crime, both being present at an attempted armed bank robbery during which they come to the rescue, disarming and subduing the criminals with only their fists and feet.

Some of the film’s drama revolves around the ring, where we get to witness Danny KO-ing another overmatched opponent. Weller is more at ease putting together combos than mouthing cue cards, and the pugilistic displays here are generally of a high caliber, if a bit too reliant on those intercut flicking-punches-at-the-camera-representing-opponent’s-POV shots that are ubiquitous in boxing pictures and that almost never have the desired immersive effect. Along with fluid footwork in close-up, Weller shows off his entire stick-and-move arsenal, including a comically overwrought bolo punch—the downright Looney Tunes-ish maneuver that consists of a distracting circular wind-up with one hand followed by a blindside straight jab with the other, popularized in televised fights by Kid Gavilan and Sugar Ray Leonard. Erotic competition over Sandra creates a schism between Danny and Andreas, though soon enough Andreas will pair off with Lisa, and a planned boxing vs. karate showdown turns into a bit of an anticlimax when the boys, prompted by no inciting incident whatsoever, sit down beforehand and decide to make their face-off a friendly exhibition match, concluding that their energies would be better utilized going after the real enemies of clean living.

The rest of the action takes things to the street, and concerns running the dastardly dealers out of town. Plot advancement relies throughout on Dickensian coincidence—Andreas, who takes physical therapy from the doctor that Sandra works for, accompanies Sandra to a boxing match featuring Danny as the top attraction, and there they both simultaneously realize that they’d both met the world champion yesterday during random violent encounters. The dialogue is simple, literal, purely functional, as when Andreas and Sandra appreciate Danny in the ring: “Wow. That guy is great.” “Yes.” It is often childish in its plodding elaboration, the needlessly fussy dotting of i’s and crossing of t’s. When Sandra asks Andreas to invite her employer to a disco after the fight, we follow Andreas walking down to the locker rooms to see the doctor and then listen to their banal exchange, the entire digression seemingly there only so that a scene of Andreas backing down a quartet of weedy punks malingering in a stairwell can be thrown in. After Andreas’s partner, Markus (Michael Messing), bangs up their shared car while helping to foil the bank robbery, there’s wholly extraneous scene of Markus at the auto dealership getting a new one, as though it had been decided that audiences couldn’t possibly be trusted on their own to mentally negotiate the logistics of how someone could get a new car.

After Lisa, an amateur aviatrix, arrives in Nuremberg from Düsseldorf by plane, Markus takes her on a brief driving tour of the city which includes a few pans over the old city walls and the area in the vicinity of the Nuremberg Castle. Later, we’ll get to see a bit of a pedestrian shopping zone that the girls do the rounds of before being kidnapped by the drug gang. These sightseeing interludes, however, are exceptions. In the main the film presents a small, tidy, strictly delimited world. Everything proceeds through the chain of happenstance encounters, as when Danny and Andreas, driving along, run across some kids on the street who, by sheer serendipity, have just witnessed Sandra and Lisa being nabbed. Everyone in urban Nuremberg knows everyone else in Macho Man and the city, as presented, appears to have a population of not more than 300 souls.

The boundaries of Macho Man’s universe are the sporting venue—gym, dojo, or boxing ring—the boudoir, and the discotheque. Inside the first, we get ample training sequences: Danny being pounded with a medicine ball; Andreas breaking boards, stones, and cinder blocks in slow-motion; and some heavy bag work and complicated abdominal exercises in the cross-cut workout routines that precede the boxing vs. karate showdown. Between gym and bedroom, the language doesn’t much change—a grapple is a grapple. “Do you really have the first dan (rank)?” Andreas asks Lisa as she enters the bedroom in nothing but a karate gi top, to which she responds, “Yes, honey. And now I’m in for close combat.” This is followed by Danny and Sandra waking to a radio program suggesting “morning gymnastics,” which Danny—who, incidentally, sleeps with his gold chain and watch on—wastes no time in turning into a naughty double-entendre. Finally there’s the disco; two of them, in fact: The Repertoire, which looks a bit like a seafood restaurant that’s been taken over by a film crew for a night, and the Superfly, the scene of perhaps the film’s strangest digression, a “break dance show” featuring first a trio of white German b-boys in skinny New Wave ties, then “the world’s best break dancer,” the Black American Tony Dawson-Harrison, performing as Captain Hollywood. (“Awesome body control,” comments Danny, approvingly, one athlete appreciating a fellow champion.)

Much of the charm of Macho Man is in its very simplicity. It imagines a world policed by dumb, forthright jocks and the babes who dig ‘em, where there is nothing to do but work out, fight, flirt, fuck, and sip fruit juice between dances at the disco, a world that, but for the interference of pesky pushers, might be taken as a version of Utopia. The film is, perhaps, a bit of a moralizing tract—a point is made of underlining the teetotaling of our athlete-heroes, which places them in sharp contrast to the narcotics-slinging villains. Any hint of heavy-handed tut-tutting, however, is offset by the winning light-headed doofiness of the entire affair, right up to the all’s-well-that-ends-well climax, which has our twin Herculeses high-fiving after cleaning out the Augean stables of the dealers’ lair then, as they stand snuggling with their rescued galpals, a pan to graffiti on the wall reading “LOVE.” (Connoisseurs of lazy movie graffiti are advised to grok the “Sex Pistols” and “LSD” tags on the wall of the same druggie den.)

However lackadaisical its art direction, Macho Man offers much in the way of sartorial delights. Leather pants are de rigeur. Danny, who throughout models a wide array of colorful ski jackets, shows up for his date in a belted teal pleather jumpsuit with black suede boots. When he, with Andreas and a platoon of their pupils, sneak-attacks the gang’s bar hangout, he does so while wearing skintight double denim and a white cashmere scarf. Last seen, as the central quartet boards Lisa’s prop plane to take a much-needed vacation, he’s wearing a banana yellow flight suit. If the Rewell collection is up to this standard, a thorough eBay trawl may be in order.

Weller, proud of his naked body though he evidently was, later had some cause to regret his work in Macho Man, in 1991 bringing a lawsuit against the film’s production company that resulted in the removal of his sex scenes from the home video release. (Hard feelings did not, however, prevent his participation in a 2017 sequel, Macho Man 2, directed by one Davide Grisolia, which I know only by its trailer.) In 1986 he lost his lightweight title to the Dane Gert Bo Jacobsen, but retook it only months later, and continued to fight until 1993, the same year that he appeared playing himself in Claude-Oliver Rudolph’s Ebbies bluff, a comedy about an amateur pug at the end of his career adjusting to life outside the ring. Weller’s own transition was rocky, and in 1999 the man who had played the bane of Nuremberg’s heroin dealers was snagged by the police while in the process of buying a heaping helping of cocaine in a hotel parking lot, carrying 200,000 in deutschmarks in the saddlebags of his Harley Davidson. Was this the end for René Weller? Anyone believing so couldn’t have been familiar with Weller’s own brand of metaphysics, which he explained in a 1996 interview: “Where I am is always the top. And should I be on the bottom, then the bottom becomes the top.”

Serving his time for trafficking, Weller passed the days writing poetry, and emerged four years later into the life of many a mid-level celebrity past their prime: appearing on reality TV shows. The first was 2004’s Die Alm - Promischweiß und Edelweiß, in which celebrity contestants are sent to a mountain hut to live the rusticated existence of farmers a century ago; in the picture above, he can be see in Die Alm with former porn star Kelly Trump. There was around the same time a stage show with stuntman Marko König and Benji le Fakir (whose act can be seen here) called Die Rückkehr der harten Jungs (“The Return of the Tough Boys”) at the Karlsruher Diskothek, and an embarrassing 2005 appearance on the German Big Brother, in which Weller drank too much, flashed his ass, and was subsequently tossed off of the show. There was more music, as well; per my friend in Berlin, Fabian Wolff, my consultant on Welleriana and so much more in German lowbrow culture besides: “Two records that aren’t even listed on Discogs, I believe he sold the first one directly out of his trunk after getting out of jail, the second one may have been primarily available for customers of a brothel in Praha.” Mellowed somewhat in old age, today Weller lives with his wife, the journalist Maria Dörk—those so inclined can watch an unsubtitled hourlong German-language television special about their home life here—and runs a boxing school in his hometown of Pforzheim. As of 2018, for 98 Euros you could hire the champ to record a WhatsApp message of your choosing.

Alongside Weller, the most distinguished Macho Man alumni is none other than Captain Hollywood, Tony Dawson-Harrison, whose ‘90s were as lucrative as Weller’s were unfortunate. Dawson-Harrison would have a string of Eurodance hits as the presiding genius of the Captain Hollywood Project, in which he positioned himself as a rapper-dancer frontman backed by a revolving ensemble of female singers and dancers. (In its present iteration, he performs alongside his wife, Shirin von Gehlen, aka Shirin Amour.) You may not think you’re familiar with the Captain Hollywood Project, but give a listen to chart-topper “More and More,” off the 1992 album Love is Not Sex… I bet you are. A Newark, New Jersey native, Dawson-Harrison came to West Germany via the U.S. Army and then stayed on, working steadily as a performer and dance choreographer, in the latter capacity collaborating with a number of second-tier boy band acts: O-Town, 3rd Wish, Primary Colorz, and the Canadian trio known as B4-4. (I cannot determine with absolute certitude as to if Dawson-Harrison worked on the video for B4-4’s 2000 melic ode to oral sex, “Get Down,” but I prefer to believe that he did.)

As an auteur work, Macho Man doesn’t offer much to contend with, unless perhaps the auteur you’re studying is Weller—director Benda seems to be a figure lost to history. But it is all the same a work of joyous vacuity, a genuine product of working-class German culture and taste presenting its star as a 1980s street Siegfried with immaculate drip. Tracing its legacy leads you down a winding path strewn with Eurodance singles, retired porn stars on reality TV, and former lightweight champs moving bricks. All of which belongs to a déclassé Deutschland which for a while had a voice through the bahnhofskinos, some of the wilder destinations to which the Lumière train has arrived. Macho Man you may dismiss as the dregs of the proud German cinema, but as the philosopher-warrior René Weller well knew, the difference between the bottom and the top is very much a matter of perspective.

The bahnhofskino photo which appears in the above text depicts the Frankfurt main station. Below, from top, are the Hannover, Cologne, Munich, Kassel, and Dresden bahnhofskinos.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to Employee Picks, as that’s the only means I have to receive remuneration for researching and writing it.