Less Rock, More Talk

On Paul Morrissey, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Ezra Pound, “Political” Art, and 1988’s ‘Spike of Bensonhurst’

If you spend a lot of time in dingy Irish watering holes frequented by retired mail carriers, and I know I do, you’ve probably seen one of those signs behind the bar that says “No Talking Politics,” or something to that effect—necessitated, presumably, because people can get awful hot under the collar when politics come up, especially if they’ve had a few. (You’ll often find FOX News playing on the television in these same joints, but that’s neither here nor there.) I’ve never seen a similar edict posted that forbids talking about movies; they can cause tiffs, too, of course, but when I think back on the more acrimonious ones I’ve been a part of or privy to, it seems to me that they usually focus on politics rather than aesthetics, stemming from a conviction that one’s affinity for whatever work is presently up for debate isn’t just evidence of a lack of taste but an actual affront, proof of the offending party’s alignment with the forces of authority and oppression, with the exact identity of those forces being contingent on one’s political leanings, i.e. the U.S. Military-Industrial Complex or Disney Groomers.

When dealing with the high overhead art of cinema, you simply can’t peel aesthetics clean of politics; the social and economic systems in which movies are made impacts what movies are made, and how they’re made. These are, to some degree at least, quantifiable factors in what makes a movie, and they shouldn’t be ignored—but neither should those irreducible aspects of living cinema when it’s ready to appear before an audience, the things a movie can express that are beyond ideology and utility, at least as readily understood. I’ve considered this irreducibility central to the medium’s attraction—its “magic,” if I can be permitted the cliché—but it doesn’t sit so easy with an age given to efficiency and keyword tags, encouraged by a discourse that winnows the onrush of immediate experience that occurs when encountering an artwork down to a handful of freeze-dried descriptors, almost invariably limited to matters of content, which presumably will allow the consumer to decide if the work in question has a strong likelihood of rubbing them the wrong way. This tendency to concise judgment and definitions can also be seen in an ongoing project to locate films and filmmakers on the ideological spectrum, as exemplified by the below piece of online detritus.

This kind of filing system is presumably useful for anyone who’s looking to avoid anything potentially offensive—that is, anything that originates from a perspective that worrisomely varies too much from their own—but it only tells you so much about what it is, exactly, that artists of whatever political stripe are up to. (The ones worth paying attention to, at least.) Firstly, there’s significant slippage in these definitions according to time and place. The Italian communist of the World War II years differed from the Italian communist of 1968, a transformation that Pier Paolo Pasolini would bemoan to the end of his life, and both would likely be a little confused by the contemporary American DSA. And can we imagine a 19th century “conservative” like Benjamin Disraeli see anything of himself in a figure like Donald Trump?

Setting these matters aside, artists tend to be rather tricky to pin down, because if they’re possessed of the powers of observation, imagination, and sensitivity necessary for the job, these will routinely overflow the boundaries of their avowed ideology—and even their ideologies can seem a bit perplexing and tending to vacillation to those who value coherency, constancy, and ironclad commitment to a Sacred Cause above all else. These last-named qualities are widely considered desirous of politicians and activists, and so it’s understandable that those who view activism as art’s principal goal should also consider them desirous of artists, along with a doctrinaire adherence to a chosen set of beliefs and a coherent, unambiguous expression of them.

Those of us who think of art as something else—say, a way to ponder insoluble questions and to explore the world and the people in it in all of their paradoxes—tend not to get too bent out of shape when the people who make it are erratic weirdos, cranks, and contrarians, or when they don’t stay securely slotted in the same place on the ideological pegboard. After his trip to Stalin’s Soviet Union, avowed man of the left and fellow traveler André Gide renounced communism in his 1936 Retour de L’U.R.S.S.; Cecil B. DeMille, a figure who would become synonymous with Hollywood at its most reactionary and right-wing, expressed no such reservations after his trip there in 1931; in fact, according to cultural historian Thomas Doherty, “DeMille looked to the Soviet Union as a lodestar, expressing his sympathy with the Bolshevik experiment and his opinion that capitalism was doomed.” I don’t mention these facts to claim DeMille as a leftist or Gide a crypto-conservative, only as two of many instances of artists’ tendency not to stay in place on any political spectrum.

There’s no U.S.S.R. to visit any more, though word of this fact apparently hasn’t reached Paul Morrissey, as fascinating a subject for study as any when considering the case of the “conservative” artist. In a 2020 interview with Sam Weisberg published in Bright Lights Film Journal, Morrissey offered up the following chestnut: “American culture has been run by the Soviet Union for the past sixty, seventy years, and it gets worse and worse and worse. It has nothing to do with Christianity anymore, that’s for sure. The Catholics have lost control of people. It’s a very sad world we live in, and I think the only adequate stories in movies and plays are the humorist ones about how awful the world is, especially the United States. They want the toilet, they want the garbage, they want the drugs, they want to have sex around the clock with their kids, and that’s the world.”

A lot to chew on there. And then how to square the above with Maurice Yacowar’s report on the director’s sentiments about Mother Russia in The Films of Paul Morrissey, in which Yacowar notes that “[Morrissey] appreciates the Soviets for suppressing liberalism, rock and roll, and other modish fatuousness. In 1993 he can draw scant comfort from seeing Western libertinism sweep across Eastern Europe under the flag of McFreedom”?1 Or, complicating matters still further, to understand how either of these seemingly contradictory positions might inform the film of Morrissey’s that explicitly deals with an encounter between eastern communism and western democracy, Madame Wang’s (1981), in which a young East German, Lutz (Patrick Schoene), a KGB agent posing as a defector looking to connect with subversive elements in the United States, shacks up with a collection of scroungers and prostitutes squatting in the ruins of the Doric-style Long Beach Masonic Temple, who take advantage of the stranger’s tendency towards stoic silence to relentlessly blather at him. And then what to make of Joe Dallesandro’s hunky handyman in Blood for Dracula (1974), a loveless lout who screws his employer’s daughters under a rude stencil of a hammer-and-sickle on the stone wall of his servant’s quarters and specializes in menacing Marxist pillow talk, but ultimately seems more interested in rising to the level of the aristocracy than banishing aristocracy, per se? The character is ostensibly the movie’s hero, dealing an agonizing death to Udo Kier’s Count Dracula and delivering the film’s closing lines—“He lives off other people. He’s no good to anyone. He never was”—but Kier’s anemic, enfeebled, altogether pathetic Count is no figure of sinister aristocratic glamor, and there’s something distinctly bittersweet about the triumph of this beefcake prole gigolo, whose ambition is to batten himself on his hosts in his own callous and calloused way.

Like his communist Puritan abroad visiting a decaying and decadent America or Kier’s out-of-time Romanian nobleman mixing with the Italian peasantry, self-described right-winger Morrissey has always been an anomalous figure in the company he keeps, most famously as the proverbial sore thumb sticking out in Andy Warhol’s Factory. Born in 1938 in Manhattan, raised in Yonkers, and educated for sixteen years in Catholic schools, in his youth the Irish-American Morrissey witnessed the ultimate triumph of Celtic papists in America with John F. Kennedy’s ascent to the presidency in 1960. (Irish-American as well were that year’s Democratic house speaker, John McCormack, and Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield.)

A mysterious photo in Yacowar’s book shows a young, bespectacled Morrissey lingering deep in the background of a snapshot of Kennedy and retinue, and Morrissey makes frequent appearances in 16mm footage taken by Jonas Mekas at the Montauk compound, Eothen, that Morrissey shared with Warhol, during the summer of 1972 when Jacqueline Kennedy, children Caroline and John Jr., and sister Princess Radziwill were guests. Was Morrissey’s story typical of a gradual Hibernian defection from Democratic Tammany Hall to a GOP redefined by Irish-American Catholic commentator William F. Buckley, progenitor to the rubicund Mick talking heads who once dominated FOX News, Bill O’Reilly and Sean Hannity? In truth, Morrissey isn’t exactly typical of anything. In a 1971 interview with Rolling Stone, he speaks highly of Franklin Roosevelt, sympathetically of J.F.K. and Teddy Kennedy, and viciously of Nixon and his “junk Republican party,” while offering as an aside that “people must really forget that the democratic system is a really dreary thing.” When asked to offer an alternative, he responds “Why not give royalty a chance? I think there is a great need for it, a great lust for it.”

Morrissey’s time in the Camelot of King Warhol began in 1965, when the two men were introduced by poet and Factory courtier Gerald Malanga. After passing through the established Factory hazing ritual of sweeping up the floors at 33 Union Square West, Morrissey, who’d been making his own avant-garde shorts and running them at a storefront cinema in the East Village that he briefly occupied, began to advise on the artist’s moviemaking endeavors, eventually taking over Warhol’s business affairs as well. In short order Morrissey was supervising almost every technical aspect of the Factory’s films, his first solo director credit on 1968’s Warhol-produced Flesh—though Morrissey, whose later interviews reflect some bitterness over the fact that his reputation will forever be overshadowed by that of his credited co-director on Chelsea Girls (1966), maintains that he’d been doing all of the heavy lifting on the Factory movies well before this. The odd-couple aspect of the partnership between the openly gay, amphetamine-popping, largely apolitical Warhol and the apparently chaste, anti-drug, conservative Morrissey has been much commented on; in spite of this, their professional relationship continued through two more films constituting “The Paul Morrissey Trilogy” with Flesh—1970’s Trash and 1972’s Heat—as well as 1971’s Women in Revolt and 1972’s L’Amour, and Warhol lent his imprimatur (if nothing else) to Morrissey’s two Udo Kier vehicles of 1974, Flesh for Frankenstein and Blood for Dracula.

This might be regarded as a marriage of convenience, of the sort that abound in the history of cinema where one party has access to considerable means and another to the ways, leading to strange unions that make actual affinities between money and talent difficult to ascertain. What is one to make of filmmakers who urge the preservation of the “big screen” theatrical experience while financing projects with money provided by streaming giants like Netflix who pose a clear and present danger to that experience? Was the real Jean Renoir the fellow traveler who made La vie est à nous (1936) and La Marseillaise (1938) in cahoots with the Parti communiste français, or the man who decamped to Italy in 1939 at the invitation of Vittorio Mussolini, son of Benito, and who played footsie with Il Duce’s regime long enough to begin a film of Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca there two years later under the dubious cover of Franco-Italian diplomacy? Everyone has their reasons, of course, and looking for movies made with “clean” money is a fool’s errand, but I suppose we all have our measures for when ends no longer can be said to justify the means, whether it’s dining with dictators, seasteading with Silicon Valley robber barons, or “jumping on a call” with Amazon.

Whatever the circumstances of the arrangement between Morrissey and Warhol, the former was an enterprising young man in a hurry to establish himself in the cinema, and the latter, ten years his senior, was well on his way as an art star and impresario. Warhol offered Morrissey a name; Morrissey offered Warhol, hardly averse to making money, a business savvy and technical proficiency that could potentially bring broader audiences to Factory films. (And, indeed, Chelsea Girls was an underground hit.) Morrissey was also rangy and svelte and pretty good-looking in a severe, imperious, and unobtainable way, and that probably didn’t hurt his chances on the Factory floor.

One might reasonably conclude, if indeed this partnership was a simple business transaction, that the reason the films that Morrissey made during his decade-long association with Warhol were filled with drug users, hustlers, homosexuals, transgendered performers, frontal nudity, and explicit sex is that these were the kinds of people and things that Warhol was interested in, and that it could be assumed the audience for an “Andy Warhol” movie would be interested in as well. Once this professional association had come to an end, however, Morrissey didn’t get to work on a remake of Leo McCarey’s Going My Way (1944) or some such wholesome, uplifting fare, but continued to make movies about people on the fringes of society: the rag-and-bone vendors of Madame Wang’s, the Times Square hustlers of Forty Deuce (1982), and the drug dealing outfits of Mixed Blood (1984) and Spike of Bensonhurst (1988)—Brazilian and Puerto Rican in the former film, Puerto Rican and Italian in the latter. The outliers in his post-Warhol period are two period pieces, 1978’s The Hound of the Baskervilles and 1985’s Beethoven’s Nephew, which might be taken as attempts to get out of the gutter, but Morrissey has called the former “the only film I’m connected with that I don’t think was very good,” and the latter is much harsher in its depiction of Ludwig van than Morrissey’s treatment of his various bands of social outcasts ever was, and neither exactly suggest a desired high road not taken due to his having been pigeonholed as a director of guttersnipes and grotesques.

Here we arrive at another facet of the Morrissey Paradox. In photographs taken of him as a younger man, Morrissey appears almost invariably disapproving, frowning, sometimes scowling. I’ve found one picture of him at a party with Warhol, Veronica Lake, and Candy Darling in 1971 (seen above) in which he seems possibly to be cracking a grin, but his head is turned in such a way as to make this difficult to say with certitude. Morrissey in interviews is often jaw-droppingly caustic: cold, imperious, absolutist, and damning in the opinions he issues on the various degenerate aspects of modern life, including rock n’ roll music. (He was, it should be noted, the original manager of the Velvet Underground, whose drummer, Maureen Tucker, would become another notable Factory-affiliated conservative.) Of his conception of Trash—originally titled “Drug Trash”—Morrissey said: “The basic idea is that drug people are trash. There’s no difference between a person using drugs and a piece of refuse.”

This statement wouldn’t seem to leave a great deal of room for interpretation, and from this you might conclude that Morrissey is in the business of producing fire-and-brimstone screen sermons, but the films themselves are as open and casual as that statement is pat, and moreover funny, charming, and palpably brimming with affection and respect for the performers that appear in them—the only subjects, aside from himself and the pre-Second Vatican Council Roman Catholic church, which the director never fails to speak glowingly of—and for the individuals that they’re portraying, even though both categories include quite a number of the sort of people of whom one might expect a traditionalist like Morrissey to feel compelled to express his dripping disapproval of.

To hear Morrissey tell things, however, it isn’t the film director’s job to express too much of anything, rather to find performers of suitable interest, provide them a slender scenario and the outline of a character as a platform, and encourage them in improvisations—the director effectively decreasing so the performer can increase. In a 1972 New York Times profile, published as Morrissey was finally beginning to emerge from Warhol’s shadow, Morrissey says: “Andy and I really try not to direct a film at all. We both feel the stars should be the center of the film.” The same profile notes some of the ways in which Morrissey’s improv-heavy films were distinct from Warhol’s; namely, in that they “had a plot and he’d edit verbiage from characters who wouldn't stop talking. He would also move the camera around for different set ups.” This was a break with Warhol’s earlier pure primitivism which encouraged even Warhol to, beginning with a pan in an unused Edie Sedgwick scene in 1965’s Space, chance the occasional camera movement, something that certain admirers of the purity of the pre-Morrissey Factory films have never ceased to curse the on-the-make interloper for.

Yacowar describes Morrissey’s aesthetic as “noninterventionist” when discussing the unscripted films he produced during his Warhol years, unusual in the freedoms that they provided their performers to create their characters in deluges of dizzy verbiage—another of Morrissey’s many contradictions being that this man who freely and frequently voices his belief in the necessity of restraint in any civilized society is among the most indulgent and uncontrolling of filmmakers. But while Morrissey’s later films still display a rare sense of spontaneity, by the time of his mid-‘70s horror movie diptych he was no longer relying on wholly on improvisation, even as he remained unusually open to input from his performers. (Vittorio De Sica, who plays a pompous nobleman in The Blood of Dracula, wrote his own florid speeches for the film, and the scene in which Dracula’s valet is drawn into in a tavern game gamble by a wily peasant was the invention of the actor playing the peasant, one Roman Polanski.)

If Morrissey’s Warhol-era films don’t necessarily feel like the product of a conservative filmmaker, one could sensibly argue that they aren’t, entirely—that instead they’re communal works, which belong as much to stars like Holly Woodlawn, Jackie Curtis, Darling, and Dallesandro. But can the same be said of Morrissey’s later, scripted works? An instructive example is Spike of Bensonhurst, Morrissey’s last completed fiction feature until 2010’s News from Nowhere, released in some overseas markets with the inane title Mafia Kid.

Morrissey, who can often be found vociferously and repeatedly insisting that he isn’t a political filmmaker, calls Spike his “most political film of all with its blatant acknowledgement of the need for some kind of control, even gangster control, placed on life.” The film is set largely in the respectively Italian-American and Puerto Rican enclaves of Bensonhurst and Red Hook, though most of the film’s actual locations are in North Brooklyn, including Williamsburg’s Fortunato Brothers Italian bakery, the then-laying-in-ruins McCarren Park pool, and a brief glimpse of row houses on Devoe St. (The palatial home occupied in the movie by Ernest Borgnine’s neighborhood mob capo, Cacetti, can be found a little further afield, on Albemarle Rd. in Ditmas Park.) Spike Fumo, played with cocky charisma by a pre-television celebrity Sasha Mitchell, is a club fighter born and raised in Bensonhurst, where he earns a little extra scratch collecting for a numbers racket run by Cacetti. Tired of flopping in fixed fights and aspiring to something more than the fate of his father—the old man is in prison upstate, having taken a rap for Cacetti—Spike tries to worm his way into the capo’s family by impregnating his boss’s daughter, Angel (Maria Pitillo), in a purely transactional bit of lovemaking. Instead he finds himself exiled from Bensonhurst, moving into Red Hook with a fellow pug, Bandanna (Rick Aviles), and his mother and sister (Antonia Rey and Talisa Soto). Seeing addicts and dealers going about their business in full sight of the police, Spike takes it on himself to play Hercules in the Augean Stables and clean up the streets, at the same time creating a mess of his own when he knocks up his buddy’s sister, Soto’s India, still running after Angel all the while. Cacetti’s perturbation turns to rage when he finds Spike passed out next to his wife in his matrimonial bed, and subsequently orders his henchmen to permanently end the kid’s dreams of ring glory by taking a meat tenderizer to his right hand.

The image of a boxer being violently robbed of his meal ticket thusly isn’t original to Spike. I suspect that Morrissey might have been inspired by the ending of Robert Wise’s The Set-Up (1949), in which banged-up prize fighter Bill “Stoker” Thompson (Robert Ryan), having refused to throw a fight on syndicate orders, is punished by having his mitt mashed into jelly with a brick. When Thompson’s worried wife Audrey Totter, who’s been begging him to walk away from the Sweet Science, finds her brutalized husband in the streets, he gasps “I won tonight,” to which she responds “Yes, you won tonight… We both won tonight.” (It stands to reason that she’s happy in the knowledge that she’s nursed her now-retired husband through his last concussion, though this always struck me as an odd thing to say to a man who’s just been beaten insensate and crippled.)

Spike’s ruination will lead to a sort of redemption, as well, though Morrissey’s film ends on a far more plangent, ambiguous note than Wise’s pat conclusion. An ellipsis of uncertain length follows the hand-smashing, after which we pick up with Cacetti making the rounds of his dominion, stopping into a vinyl siding-clad triple-decker hand-in-hand with his grandson—and who should he be going to visit but India, Spike, and their two young children. Spike now wears the uniform of a beat cop; the gig, we learn, was lined up for him by Cacetti. Lashing out against his destiny no longer, back where he belongs in Bensonhurst, Spike has settled into his place in the social order of the neighborhood as husband, father, and workaday breadwinner. The film closes with a wordless exchange of glances between the now-chastened Spike and India, following a bit of casual racism from Cacetti, commenting on the new baby’s color. Spike seems now to have lost his old braggadocio and fight, and there’s a sadness in seeing him reined in, because that cocksure, yappy kid was charming in a boneheaded way—but he also has a new calm, and in our last glance of him, looking into India’s eyes, his expression might be described as a kind of rueful contentment.

From Dallesandro’s stake-driver to the eponymous Spike, Morrissey’s films show a deep ambivalence towards social climbers, depicted as sowers of discord and violence. (Yet another irony, as several of the Factory cohort recall Morrissey as being set apart by a hustle and work ethic that were unusual in that crowd.) Morrissey’s comments leave little doubt that he views the blunting of Spike, his comeuppance and submission, as a necessary part of maturation, and we might very well call this a conservative proposition. But one of the handful of filmmakers of whom Morrissey speaks with open admiration is John Ford—and like Ford, describing the tensions that exist between the individual and the community, Morrissey doesn’t turn a blind eye to the shortcomings of the community.

Spike, who’s quick to condemn the rampant drug use he finds in blighted Red Hook and tout the superiority of the civilization in orderly Bensonhurst, never seems to make a connection between the misery and squalor he sees on the streets of the Puerto Rican neighborhood and the drug-dealing operation that Cacetti and company oversee back home. If the Cosa Nostra do manage to impose a certain degree of admirable order over a few blocks of Brooklyn, they’re still implicated in a broader pattern of graft and corruption: Cacetti, gesturing to a framed portrait of Mario Cuomo, informs Spike that he dutifully contributes money to “the liberal politicians—all that garbage,” and later he’ll be seen at a Bar Mitzvah glad-handing with a coke-sniffing, soft-on-crime congresswoman who, in her elaborate millinery, appears to be definitely intended as a caricature of Bella Abzug. The clannishness that keeps the neighborhood together has a very ugly side, visible when Bandanna and some friends are found strolling through Bensonhurst one night and are rushed en masse for the crime of being Puerto Rican in an Italian neighborhood. (A year after Spike’s release, Yusef Hawkins, a black teenager from East New York, would be murdered by a white mob in Bensonhurst; the same year, another Spike presented his Do the Right Thing, a film not irrelevant to the matters at hand.) There is nothing idealized in Morrissey’s depiction of Bensonhurst, but it’s where Spike’s home and heritage are, and that, Morrissey seems to say, is about the best you can hope for in a world that’s gone swirling down the shitter.

The words “garbage” and “toilet” are staples of any Morrissey interview, and central to the Morrissey worldview. The poet Bill Berkson’s posthumously published Since When: A Memoir in Pieces offers a pertinent thumbnail sketch of Morrissey at the end of the ‘60s: “An expression Jim (Carroll) picked up on, Paul Morrissey’s way of saying ‘Whaat ga-arbage’—became multipurpose at some point. Jim particularly loved and perfectly mimicked the bright disdain with which Morrissey intoned this phrase and used it often and appropriately. He had that stunning, mad Irish American Catholic mixture of skeptical knowingness and ceremonial awe. The only book I remember him giving me was the fourteenth-century manual on contemplation The Cloud of Unknowing.”

In one form or another, this sense of the world as a wastebin makes its way into every Morrissey film, a treasured motif that he connects to an early encounter with the sewer-set climax of Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), of which the filmmaker has said: “This notion that the conflicts of modern life, so debased and degenerate, are fittingly placed in the ultimate setting of human waste, was an idea that never left me.” His films are heaped with cast-offs, human and otherwise, and his known enthusiasms are remarkably consistent in their concern with refuse. Mixed Blood gives a starring role to the Brazilian actress Marília Soares Pêra, best known for her role in Héctor Babenco’s Pixote (1981), and the appeal of that film to Morrissey, with its depiction of uncared-for youth struggling to survive by rummaging through rubbish bins in waste land favelas, should be rather apparent. So, too, the draw of the reality television show Hardcore Pawn (2010-14), about a family-owned and -operated pawn shop located on Detroit’s 8 Mile road, in which proprietor “Les” Gold and his two children are confronted by a steady stream of victims of capitalism trying to unload their junky heirlooms for a few bucks of gas money. (Here we are not far from the community built around the outdoor flea market in Madame Wang’s, stocked with discarded doorknobs and, of course, heaps of toilet seats.) In Spike, the key toilet appears in the overcrowded public school where India and Bandanna’s mother teaches, trying to educate zoned-out kids in humankind’s noble heritage from inside a repurposed bathroom.

All of this may sound unremittingly grim, but Morrissey is here as ever a firm follower of the “Make ‘em laugh” pleasure principal, serving up a bitter pill philosophy with an easy-to-swallow sugar coating. (Otto Preminger’s brusque review of Heat in a panel following its New York Film Festival screening—“Depressingly entertaining”—hits the nail rather squarely on the head.) Spike is, beat-by-beat, an almost deliriously enjoyable viewing experience, as was confirmed by the steady gales of laughter at a public screening last month; the melancholy only sinks in later. The movie bops along on a wall-to-wall soundtrack of buoyant contemporary Italian pop, with songs from the 1984 album Malattia d’amore by Pupo, neé Enzo Ghinazzi, given a particular place of pride. Spike pitches woo to Angel in an outdoor line dance sequence where they, along with dozens of young Bensonhurst Italian-Americans, move in swoony harmony to the honeyed strains of “M’innamoro di te,” a single by the Genoa group Ricchi e Poveri. The incongruity of rangy, macho, pushy Spike going through the slow, feline, fey motions of the dance is very funny, as is his explanation to Angel of the spell the music casts on her: “That’s ‘cause youse a good Italian girl. This music is like ya heritage, ya know? It’s been around for hundreds of years.” (The song was released in 1981.) This scene, however, follows on another that shows lockstep racial solidarity in a darker light—the brutal scuffle with the Puerto Rican outsiders, its bone-crunching body slams ironically scored to Ricchi e Poveri’s feather-light “Sarà perché ti amo.”

When not busy railing against rock n’ roll, Morrissey has proclaimed his preference for “ethnic” music, and in Spike, as in Mixed Blood, he turns his focus on hyphenated-American communities who haven’t yet wholly been rendered down in the melting pot of U.S. consumer capitalism, which he seems to regard as something like a boiling cauldron that disintegrates the bonds of family, community, and tradition in order to create atomized, isolate individualists, the ideal marks for a junk-peddling culture. (He has a particular distaste for fast food, as evidenced in Spike when Cacetti’s wife tells her stockbroker to invest in “high-fat foods,” and in Madame Wang’s when a bloated matriarch played by Jimmy Maddow stuffs her son with Big Macs.) There is, nevertheless, a dose of irony in Morrissey’s association of Angel with jukebox fantasies, as the contrast he builds in his treatment of Spike’s two romances is one between the forgotten richness of real feeling and the poverty of aspirational fantasy in a plasticine present.

Morrissey acquired a certain infamy for the then-novel sexual explicitness of his films, particularly those with Dallesandro in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, but he is explicit only when dealing with sex-as-business: Dallesandro fondling his landlady for a rent reduction in Heat; the various erotic negotiations that make up Blood for Dracula; or the assignation between a young prostitute (Christina Indri) and a diaper-clad client in Madame Wang’s, among that film’s myriad perversities. The backseat barter between Spike and Angel doesn’t go further than Spike unbuckling his belt in preparation to go to work planting his seed, but this suffices to establish the basis of their relationship in material exchange—his body in trade for her dowry—rather than spiritual communion. By contrast, Morrissey is positively coy when dealing with deeper connections, as is evident in his treatment of the slow-blossoming bond between Spike and India. The evolution of their relationship is depicted largely as a series of silently exchanged glances, like those that conclude the film, and there’s a jolting moment when Bandanna chides Spike for chasing after Angel after he’s gotten India pregnant—jolting, because we haven’t up to this point so much as seen them kiss. Their romance, the pivotal element in Spike’s eventual settling, occurs off-screen, as though Morrissey is too discreet to barge in on something so precious. (Yacowar draws an apt comparison between the treatment of the Spike-India relationship and the off-screen consummation between Kier’s Dracula and Milena Vukotic’s spinster Esmerelda in the otherwise ultra-graphic Blood for Dracula.) His own life seems to have been marked by a similar discretion; as Warhol recalled: “The running question was, did [Morrissey] have a sex life or not? Everyone who’d ever known him insisted that he did absolutely nothing, and all his hours seemed accounted for, but still Paul was an attractive guy, so people constantly asked, 'What does he do? He must do something...’” In latter-day interviews, one can find the oft-censored Morrissey preaching the virtues of “commonsense censorship.”

So in Morrissey we have both Puritan and pornographer, another paradox to add to a pile that already includes: anti-communist admirer of steely Soviet resolve, terminally pessimistic director of mostly comic films, noninterventionist filmmaker who believes in the necessity of control, conservative Catholic who was a fixture in an underground milieu filled with drug users and deviants, and proud independent operator who believes in submission to traditional hierarchies… Looking at Morrissey’s many, seemingly antithetical facets, some might find evidence of canting hypocrisy—“Is Paul Morrissey,” asks Yacowar, “the poor man’s Cecil B. DeMille, who wallows in the orgies around the golden calves, then covers himself with a pat pontification?” The author answers his self-posed question in the negative, which might be expected given that he wrote a whole book about Morrissey, finding in his films a laudably persistent moral humanism and a vision that “embraces the sinner even as he condemns the sin.”

That’s as may be, but in truth I’ve never put a premium on artists resolving the disparate aspects of their personalities into irreproachable and airtight value systems to be communicated in crystalline transparency through their work; if all questions are settled before starting out to make a film, why make the thing at all? This is probably why I value DeMille’s filmography, with its tug-of-war tension between Christian piety and SM perversity, more than Yacowar seems to, and why I keep a bedside vigil with the ailing cinema, which still sometimes allows bits of happenstance and irreconcilable information to slip in and muddle messages, those bits of disarray that remind us of lived experience in all its complexity and confustion. In addressing the anomalies of Morrissey and his films, it’s worth quoting some of the director’s own stated views of character: “People are really capable of being many different things. If it’s all written down for the actors and they read their parts in advance and they figure who they are and what kind of person they’re going to play, they play that kind of person all the way through the script. When it’s informal and free, they can be lustful here and childish there and sympathetic here and not so sympathetic in other scenes. I found it very useful as far as characterization goes.” As he would succinctly put it elsewhere: “I like complicating a character. If you make them embody contrary thinking then they’re a little bit funny, a little more human.”

This human quality is what I value in the films of this most self-effacing of filmmakers, Paul Morrissey, who never wastes an opportunity to swipe at the Frenchified notion of the vaunted auteur—though I would argue that his notion of auteurism is based in a common misinterpretation of the actual Cahiers du Cinéma line, which was not so much premised on a director’s total dominion over every element of a production but on the understanding that a mechanical art being practiced amidst the hurly-burly of a film shoot couldn’t perforce be truly controlled, only channeled, and that every film was a combination of intent and accident, and that an identifiable style wasn’t something hidebound but rather a pattern of responses to unpredictable circumstances, and that practitioners of an artform so close to life shouldn’t be valued for winnowing life down into something so narrow as a dunning, repetitious message, but rather for being consistent in their inconsistencies. All of which is rather more complicated than just saying “The director is the omnipotent force responsible for making a movie,” which is what auteurism usually gets boiled down to, because as we know, people have a positive passion for simplifying things.

The cut-and-dry designation of “right-wing filmmaker” is a meager vessel to attempt to decant a bundle of contradictions like Morrissey into, just as the designation “left-wing filmmaker” struggles to iron out the stubborn wrinkles in the thinking of Pier Paolo Pasolini, who would come to resemble Morrissey more than a little in his revilement of consumer culture and his desolate surety, late in his life, that apocalypse was nigh.

Both Morrissey and Pasolini repeatedly took slum-dwellers and those society shunned and abandoned as their subjects, in Pasolini’s case designated as the “sub-proletariat,” in whom potentially regenerative vestiges of the peasant culture of centuries past survived in a brutalized present. Both men perceived that seemingly irreversible harm had been done to the most vulnerable of their countrymen and -woman by postwar prosperity, the erosion of tradition by pervasive consumerism that followed and, eventually, the license encouraged by an emergent “counterculture.” “I’m scared of these slaves in revolt,” said Pasolini in an interview conducted the day before his murder, “Because they behave exactly like their plunderers, desiring everything and wanting everything at any price”—a statement which neatly summarizes the Dallesandro-Kier dynamic in The Blood of Dracula. I know of only one instance of Morrissey speaking of Pasolini on record (he briefly calls him “great” in a 1980 interview), though he’s gotten somewhat more expansive discussing his admiration of 1963’s Il Gattopardo, another film of fading aristocrats whose card-carrying Commie director, Luchino Visconti, embodied an impressive internal incongruity, being both Comrade and to-the-manor-born Count.

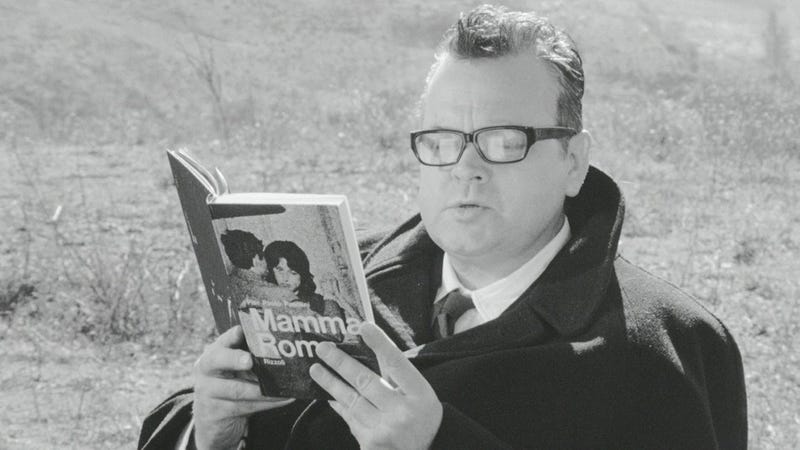

If the films of radical right-winger Morrissey, at least in terms of presiding themes, find ready comparisons to those of left-identified filmmakers like Pasolini and Visconti, this could be accounted for by a kind of horseshoe theory of socio-political abjection—the anguished reactionary traditionalist shares with the revolutionist firebrand the conviction that the existing system is irredeemable, and differ though they may in their prescriptions for what made or might make a better world, this sense of horror gives them more in common with one another than either share with the middle-range liberal who imagines that the necessary amelioration of the catastrophe of contemporaneity can be incrementally improved within the present parameters of possibility. You don’t exactly have to leap a vast chasm to get between Pasolini’s conception of the industrialized world as a pigsty rife with cannibalism in Porcile (1969) and Morrissey’s of the United States as a dumping ground populated by wretched, dehumanized gleaners in practically every film he made. It was Pasolini who began one of his poems “I am a force of the past/Tradition is my only love”—the lines are spoken in dubbed Italian by a film director played by Orson Welles in La ricotta, Pasolini’s contribution to the 1963 omnibus film Ro.Go.Pa.G—but only the fact that Morrissey generally avoids such grandiloquent language betrays that the words aren’t his own.

Some sense of Pasolini’s view of “the past” may be gleaned from his relationship with the work of Ezra Pound, another radical modernist steeped in tradition. Born in Idaho in 1885 and raised in the vicinity of Philadelphia, Pound had established himself as the dean of modernist literature in the course of a series of editorships that took him first to London, then to Paris, before he finally settled in Rapallo, in the north of Italy, in 1924, two years after Mussolini’s March on Rome. At the close of the Great War, which Pound viewed as a devastating blow to the European civilization he’d so admired, Pound found what seemed a reasonable explanation for the cataclysm during a chance 1918 meeting with Maj. C.H. Douglas at the London offices of socialist journal The New Age, where Pound contributed a regular column. The founding prophet of the “Social Credit” movement, a theory of economics that proposed the government issuance of debt-free money, Douglas blamed the war on finance capitalism, the “usury” which Pound had already come to disdain as much as he did democracy, and which he associated with international Jewry. Thusly, publicly proselytizing for his first great cause, “Social Credit,” led Pound to his second, a passion for fascism generally and for Il Duce’s regime specifically, the virtues of which he extolled over a series of radio broadcasts delivered first from Radio Rome, then from the Nazi Germany-controlled puppet state established in the north in response to the rapid progress of the Allied Italian campaign, the Republic of Salò.

The capital-in-exile city, located on the banks of Lake Garda in Lombard, would be the setting of Pasolini’s final film, Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, 1975). During the film’s culminating cavalcade of tortures, witnessed via binoculars by giggling spectator Aldo Valletti, a quotation from Pound’s “Canto XCIX”—part of a 116 section poem cycle that Pound labored on from 1915 to 1962—is heard on the radio, concluding: “Small birds sing in chorus/Harmony is the proportion of branches/as clarity.” (The Canto in question, Pound’s re-writing of the Kangxi Emperor’s 1670 Sacred Edict, reflecting his long engagement with Confucianism, wouldn’t have been broadcast in Salò, not having been published until 1959 as Thrones de los Cantares XCVI-CIX.)

Soundtracking the barbaric slaughter of innocents with Pound’s lyric extolling of Confucian social order may be read as an implication or indictment, but Pasolini can elsewhere be found approaching Pound in a positively collegial manner. In winter of 1968, a decade after Pound’s long imprisonment by the United States government on charges of treason had come to an end, Pasolini presided over a television interview with Pound that was filmed for RAI television italiana in Venice, the director having stepped in at the last minute to cover for the Sicilian poet Vanni Ronsisvalle. Pasolini begins the interview by quoting the opening lines of Pound’s “A Pact,” his grudging 1913 address to another pioneer in poetry—“I make a pact with you, Walt Whitman-/I have detested you long enough”—then repeats the same lines, with Pound’s name now replacing Whitman’s. He doesn’t mention the last four lines—“It was you who broke the new wood/Now is a time for carving./We have one sap and one root-/Let there be commerce between us”—but the impression of an extended olive branch is clear enough.

By the time of a December, 1973 article, published a little over a year after Pound’s death, Pasolini even seems to have come to regard Pound as a kind of kindred spirit in his veneration of a lost rural tradition, writing: “Everything that came to Pound from this peasant world by way of his father and the mythic figure of his grandfather can be seen in the way Pound idealized Chinese culture. Pound’s China is born from that archaic world of the peasants from which the modern American farmers have descended. Pound… was not at all an Orphic poet. He wanted—he firmly and madly desired—to remain in that peasant world… His ideology was made up of nothing less than the veneration of the values of that world (revealed to him in concrete form by pragmatic, virtuous Chinese philosophy.)… The ‘coherence’ of the Cantos consists in a retreat to the heart of the peasant world for which ancient China is a symbol; where governments become ever more tyrannical and illuminated.” While not overlooking Pound’s vulnerability to “reactionary ideology,” Pasolini ascribes it to his subject’s “peasant background,” which may seem a bit rich considering that mythic grandfather, Thaddeus C. Pound, had been a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, but Pasolini made no such distinctions, considering Americans as a whole the descendants of sub-proletarian immigrants.

If Pasolini felt he could afford to be indulgent of Pound’s fascism in the mid-‘70s, this was because he had come to view the fascism of Blackshirts, jackboots, and castor oil as a defanged relic of the pre-industrial past, an “archaeological fascism,” and he was now consumed with a more pernicious breed of contemporary fascism, which he named in this excerpt from a December, 1974 column in L’Europeo: “I believe, I profoundly believe, that the real fascism is the one that the sociologists have called, with too much good will, ‘consumer society.’” This new enemy, Pasolini insisted, had succeeded in remaking its subjects’ and colonizing their inner lives with a totality its predecessor might have envied; as he put it in his 1973 article ‘Acculturation and Assimilation’: “No fascist centralism ever managed to do what the centralism of consumer civilization has successfully accomplished.” Salò was about the Italy of 1945, but also about the Italy of 1975, showing the dawn of the country’s new, hedonistic fascism in the last spree of its old fascist regime.

Pound’s “detestation” of Whitman would seem to have been a matter of anxiety of influence above all else—in the years prior to his beginning on his Cantos, he had been known to slip into imitation of Whitman’s repetitious, cataloguing metric, and he always retained something of Whitman’s preening, affected self-presentation, as well as Whitman’s conviction of poetry’s destiny as a dynamic force in the world. (When asked about the possibility of a poet “actively engag[ing] the world in which he lives” in the RAI interview, Pound replied “It’s necessary, if truly lived… not to drift to the periphery,” just before proclaiming “politics” as “a provisional word,” and “only vocabulary.”) Pasolini, it may be argued, had more motive for his enmity to Pound. Pasolini’s younger brother, Guidalberto, had been killed at age 19 in 1945, while fighting to liberate Salò with the Osoppo-Friulian Brigade of the anti-fascist Partito d’Azione near the Italian-Slovenian border. That same year, two anti-fascist Italian partisans would drag Pound out of his redoubt in Sant’ Ambrogio, after which he would begin his long confinement at the U.S. Army Disciplinary Training Center outside Pisa. If Pasolini was willing to make peace with Pound, it’s perhaps because he was increasingly, despairingly conscious of his own inability to change the course of contemporary events through his activity as a thinker, poet, and filmmaker, and had occasion to wonder how much an American crank babbling about monetary theory on the radio had actually contributed to his brother’s death. As America had Whitman as its bard, so Italy had poets who seemed to address the nation as a whole—Dante long before nationhood, and then that first Duce, the proto-fascist d’Annunzio, who’d ruled briefly over the Free State of Fiume. Pasolini had perhaps envisaged himself as following in their footsteps, only to discover that artists no longer shaped the destinies of nations, if indeed they ever had. Mussolini had begun his career as a journalist and novelist, but in time found a more efficacious outlet for his active imagination.

Pasolini’s dimming hopes for the future of Italy and humanity as a whole are evident an essay titled “Abiura dalla Trilogia della vita” (“Abjuration of the Trilogy of Life”), written while he was at work on Salò. Where his trilogy—consisting of Il Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales (1972), and Il fiore delle mille e una note (1974)—had been undertaken in the belief that fallen humanity could be rehabilitated by uncorrupted, unfettered eros, by the time of Salò, Pasolini had come to believe that the liberational promise of sex had been demeaned by the commerce’s cruel mandates. Wrote Pasolini: “First: the progressive fight for expressive democratization and sexual liberalization has been brutally overcome and frustrated by the consumerist power’s decision to bestow a wide (and false) tolerance. Second: even the ‘reality’ of innocent bodies has been violated, manipulated and tampered with by the consumerist power: indeed, such a violence against bodies has become the most glaring fact of a new human epoch.” Rather than an Age of Aquarius, Pasolini saw a new kind of immiseration resulting from the sexual revolution, so-called, concluding that “a [kind of] society that is tolerant and permissive is the one in which neuroses are most frequent, insofar as such a society requires that all the possibilities it allows be exploited, that is, it requires a desperate effort so as not to be less than everybody else in a competitiveness without limits.”

Pasolini’s idea of the permissive society as an instrument of control more finds an echo in a statement of Morrissey’s: “Pandering to basest instincts, the stupid liberal says ‘Let it all hang out,’ ‘Do whatever you feel like doing.’ With three big carrots, sex, drugs, and rock and roll, they rule, they have the power, they control life under them with a much stronger hold than the Soviet dictators with their enforced puritanism ever dreamed possible… Unfortunately, once you’re cast adrift from custom and tradition they all want it on their own inverted terms.” Liberation, according to Morrissey, is enslavement—whereas conversely, “In the mind of a conservative everything good lies in an ideal reality. That reality is attainable through some kind of control.”

While certain affinities exist between Morrissey and Pasolini, or Pasolini and Pound, or even Pound and Morrissey, their divergences are equally vast. Each has their individual Utopian strain, a vision of “ideal reality,” but their visions vary, as do the ways they impress themselves on their work. Pasolini’s reverence for tradition is not, as in the cases of Morrissey and Pound, grounded in a desire to return to an imagined orderly past, but in a desire to use the desirous elements of that past to remake a moribund present. (Wrote Pasolini in 1962: “It is necessary to tear the Monopoly of tradition from the hands of traditionalists. Only revolution can save tradition.”) Morrissey may share Pound’s belief in hierarchal social arrangements as the best guarantor of maintaining peace and happiness, but where Pound’s Cantos provide instructive maxims, Morrissey’s is a gallows humor art comprised largely of negative examples of what occurs when men and women are abandoned to freedom, and in them characters who might be regarded as mouthpieces for their director’s wisdom are no more or less ridiculous than the rest. (When India and Bandanna’s law-and-order minded, Italophile mother meets Spike, she enthuses over Italy’s legacy of Great Men: “Julius Caesar! Mussolini! Al Capone!”)

When an artists’ ideal reality comes to seem out-of-reach, what results are frequently works of despair, evocations of squandered potentialities and all-consuming desolation. There will be no end to the sifting through the rubble of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” in search of meaning, but there’s at least some general consensus that Eliot, an American expat who’d decamped to Europe in search of civilization like his friend and editor, Pound, was expressing some of the same postwar malaise that had driven the man he called “il miglior fabbro” (“the better craftsman”) in the poem’s dedication into the waiting arms of Maj. C.H. Douglas. In addition to the howl of Salò, Pasolini left behind a draft unfinished novel of 133 fragments and some 500 pages that he’d been working on at the time of his death, Petrolio. (Pasolini had planned for the finished novel to be four times as long, a project comparable in scope and formal ambition to Pound’s Cantos or Gregory Markopoulos’s 80-hour Eniaios cycle.) Finally published in 1992, among the more memorable passages in its disjointed fragments is a description of apocalyptic environmental destruction: “Finally, an immense pile of trash appeared, in a sort of large hollow in the earth, with an /unbreathable acid/ odor and the sparkle of tin and the more <opaque> sparkle of plastic; part of the trash had been burned, leaving a barren expanse of ashes; the rest was burning. The fires hissed, faded, or flared up suddenly, fed by the polluted wind, in the most absolute solitude.” The desolation of Pasolini’s final works was matched by his own finish. When a woman living in a shack on the beach in Ostia discovered the murdered Pasolini’s body on the morning of November 2nd, 1975, she initially mistook the corpse for a discarded bag of refuse. Gary Indiana, writing about Pasolini and his paradoxes, summed up the final irony of his death thusly: “For this worshipper of vanished times and values was the victim of the most entrenched prejudices surviving from the past. Embracing the stereotype of the noble peasant, he was hounded throughout his career by the homophobia and pious ignorance of peasants, and finally got murdered by one.”

Morrissey may be envied the fact that, unlike Pasolini or Pound, he seems not to have had any cherished illusions of potential regeneration to be disabused of, never having wavered from his serene knowledge that ours is and has long been a landfill world, a Waste Land where the center had long ago ceased to hold. When the filmmaker was emerging from out of Warhol’s shadow at the beginning of the ‘70s, as in the aftermath of World War I, the scent of garbage seems to have been thick in the air. The New York Dolls, a proto-punk five piece whose gender-bending sartorial style owed something to that of Morrissey’s leading ladies, released a debut single, “Trash,” in 1973.2 Baltimorean John Waters, ten years Morrissey’s junior, began his own trilogy—the so-called “Trash Trilogy” that consisted of Pink Flamingos (1972), Female Trouble (1974), and Desperate Living (1977)—just as Morrissey and Pasolini were finishing up theirs. Waters, like Morrissey, had a nose for the stench of all-American filth, though where Morrissey loudly bemoaned the spectacle of waste, Waters seemed to revel in all the splendid squalor. Watching Desperate Living, one distinctly has the sense that Waters regards the rag-and-bone outlaw community of Mortville—once Edith Massey’s despotic Queen Carlotta has been dethroned—as a rather pleasant place to settle down.

This crucial difference notwithstanding, Waters and Morrissey’s films are not so unalike as one might think. Both are before all else comic artists; Morrissey may have been appalled by the tackiness of contemporary America and Waters tickled pink by it, but both regard laughter as the proper response to the spectacle. Both share a predilection for casting transgender and transvestite performers—in the case of Morrissey’s Women in Revolt (1971), all three female leads: Curtis, Darling, and Woodlawn. And finally, both are united by the unmistakable fondness with which they regard their often ridiculous, sometimes duplicitous, but never despised characters, and the actors who perform as them. “I’m sensitive to all the characters equally,” Morrissey once stated. “I have no favorites. In an immoral world no one is better or worse than any other.”

This generosity—one is tempted to call it Renoir-esque—renders even the most seemingly straightforward of Morrissey’s works far more difficult to pin down when they’re subjected to any real scrutiny. Women in Revolt, for example, is usually succinctly summarized as a parody of the Women’s Liberation Movement, a return fire from the Factory following radical feminist Valeria Solanas’s near-fatal shooting of Warhol in 1968. (Morrissey was in the toilet, of all places, when the shooting went down.) But the film itself complicates such a reading; writing in his Screening the Sexes, Parker Tyler notes that “mere description is beggared when it comes to rendering into words what Women in Revolt ‘is,’” before going on to summarize the film’s essential paradox: “The gimmick and the grandeur are all together. We never forget, nor are we meant to forget, that these ‘actresses’ are males. And they are most male when most absurdly pretending to be female… Somehow [the film] provides a transcendent insight, piercing and not without blood, into what the Marilyn Monroes and Jean Harlows of film history always used to be about.”

Women in Revolt, in its unusual approach to the feminist phenomenon, is a work no less rich in internal tensions than Henry James’s 1886 The Bostonians, the book that Richard Lansdown called “A remarkably experimental modern novel, written by a man of conservative values. It is judgmental about people with whom the author identified, and lenient towards attitudes hostile towards large areas of James’s own intellectual and personal inheritance. The strength of the contradictions embodied in the novel are a guarantee of the pleasure it has to give.”

Not everyone would agree with Lansdown’s assessment. When James’s portrait by John Singer Sargent, commissioned on the occasion of his 70th birthday, was put on display at the Royal Academy exhibition in May of 1914, a suffragette by the name of Mary Aldham, using the alias Mary Wood, produced a meat cleaver and gave the area of the canvas around James’s right eye three solid whacks. Explaining her actions later, she wrote simply “I have tried to destroy a valuable picture because I wish to show the public that they have no security for their property nor for their art treasures until women are given their political freedom.” Aldham didn’t make any mention of having read The Bostonians, but anyways she doesn’t strike me as the type to go in for Jamesian ambiguity.

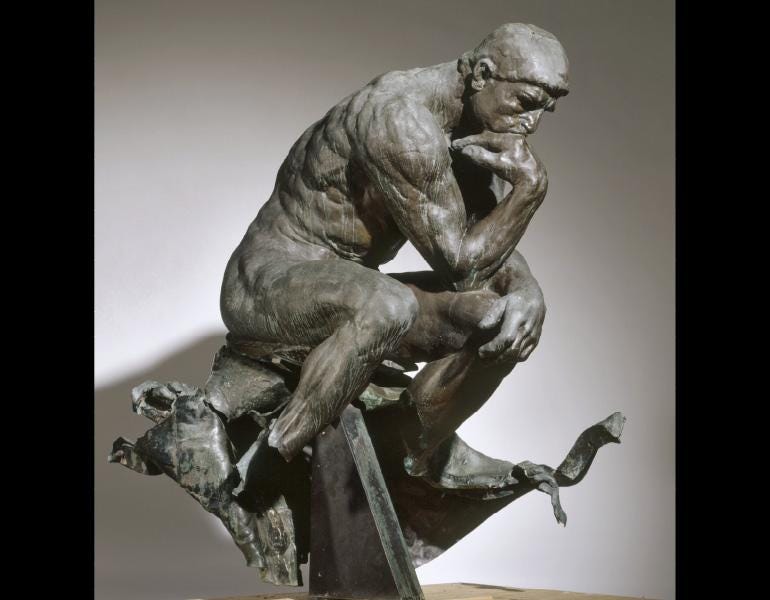

As a general rule, I don’t go in for shooting artists or vandalizing works of art—above is the distinctive cast of Rodin’s The Thinker that sits outside the Cleveland Museum of Art, damaged by a dynamite blast in March of 1970—regardless of what I may think about the justness of their cause for doing so or the offense of the work. I caught a bit of Matthew Vaughn’s X-Men: First Class (2011) on a bar television set the other day, and though I can say unequivocally that it is the most atrocious-looking thing I have ever seen, I believe it should be preserved for future generations, like Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens (1935), as a testament to the banality of fascism—the old-fashioned kind that Pound advocated for in the case of Triumph, the consumer culture sort that Pasolini decried in the case of First Class.

That same tendency towards conservancy means I can’t get on-board with Morrissey’s advocacy for “commonsense censorship,” a phrase which begs the question: “Whose common sense?” (Those who call for limitations on free speech often seem to do so under the inexplicable assumption that it will be themselves or people who share their values who’ll be setting the limits.) Because I’ve read too many Edward Yang interviews, I can’t swallow Pound’s prescription of sublime Confucian order as the panacea for the untidiness of contemporaneity, and though I rate Pasolini’s as a first-class mind, he gets positively weird on the subject of students with long hair, among other things. On the whole, all three men fired got off some cogent points about consumer capitalism and the downsides of modern western democracy, but then I’ve been known to down a Big Mac from time-to-time, and I can’t pretend my soul is immaculate. Nevertheless, in either conflict or concordance, each artist has given me something—we can call it simply, as Lansdwon does, “pleasure.”

There is a certain kind of with-us-or-against-us binary mind that regards all talk of “nuance” as so much anxious prevaricating by insufficiently committed aesthetes trying to preserve their “problematic faves” from the dustbin of history with pleas to keep art clean and clear of politics. It would be insupportable to claim that artists’ personal politics—or their absence of personal politics—are wholly irrelevant to the work that artist produces; in fact, I don’t know that I’ve ever heard anyone say as much. (Arguing against the efficacy or interest of art-as-activism is another matter.) The fragments of Petrolio are difficult enough to make sense of as it is, and to understand Pasolini’s burlesqued treatment of an “anti-Fascist reception” in the novel—somewhere between the Dostoevsky of Demons and the Tom Wolfe of Radical Chic & Mau Mauing the Flak Catchers—it behooves one to know something of Pasolini’s attitude towards contemporary student radicals. Pound the poet cannot be separated from Pound the crackpot social-economic theorist, nor would he have asked to be, viewing the roles as inextricable, and part of the same grandiose mission.

The figure of the absolutist aesthete goes to the mat without so much as getting a punch in, as strawmen tend to. The real debate, however, has never been between parties advocating for strictly political or apolitical readings of art, but rather between reductive and expansive attitudes towards it. Can most any work be clarified into a descriptive kernel: “fascoid,” “as relevant now as ever,” “copaganda,” “pornography,” “a call to action,” and other old favorites? Is the essential thing to know how a film or novel might vote or what rallies and reading groups it might attend if it were suddenly to acquire human form, or are there other factors at play that require that plodding, painstaking business of digging through layers of discordant data and multivalent meanings, a process that requires living with art rather than cataloguing it, pinning it, and shelving it away in little Letterboxes?

Understanding the idiosyncrasies of artists’ stated ideologies—and with Morrissey, Pasolini, and Pound we’re dealing with three particularly idiosyncratic ones—can tell you something about their work and what they may be trying to put into it, but it can’t tell you everything, at least not if one believes an artwork can pose questions alongside certitudes, access vagaries of experience that can’t be jammed into boxes marked “right” and “left,” and present a view of the world more expansive than that of the meager individual that produced it. An observation made by Néstor Almendros in his Man with a Movie Camera, referring specifically to cinema, speaks to this final point. “Films are sometimes superior to their makers,” writes Almendros. “This may explain why at times I like films made by people who I find unpleasant or whose ideas are contrary to my own. It is possible to sit through a film made by someone who personally doesn’t deserve five minutes of one’s time.”

How to explain the phenomenon that Almendros describes? I suspect it amounts simply to a taste for new pleasures, new beauties, and new manners of expression that overwhelms the distaste for an individual’s personality or ideas. Whatever differences lay between them, Pasolini and Old Ez shared these tastes, this common root and sap, a fact evident in the Pound interview when Pasolini admiringly quotes one of the “Pisan Cantos,” written at the beginning of Pound’s incarceration, to the poet himself: “Under white clouds, Cielo di Pisa/out of all this beauty something must come.”

It may be that these lines don’t quicken your pulse—nor the dewy loveliness of cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli’s images in Il Decameron, which seem to have come from the dawn of the world; nor the image of sublime submission that ends Spike. This may considered a simple matter of taste—“What I do in my house, you might not do in your house,” as another American poet, Luther Campbell, once put it—though no matter of taste is entirely simple, for an individual’s sense of the beautiful tends to have not a little to do with their sense of truth.

We are coming close now to Keats and his Grecian urn—for the airy Romantic idealist an axiom of aesthetic pleasure, for the pure materialist a trinket left behind by a hypocritical slave-owning civilization. Most of us, myself included, probably lay somewhere in-between on this spectrum, though in recent years we’ve seen quite a bit of culture writing that touts the virtues of inuring one’s self to the pleasures that a work of art might give because it originates from a sensibility alien to one’s own, and this strikes me not as a matter of progress, but of impoverishment of the imagination. Asked for his advice to the young in that ‘68 interview, his final for television, Pound’s brief response was “Be curious.” I take this to mean taking an active interest in things standing outside of one’s self, in perspectives outside of one’s own, and this is what I fear is becoming ever-scarcer when characters in narrative art are judged for their “relatability,” when film stills are splattered across social media with the descriptor “Literally me,” and when demographic representation is discussed in terms of “feeling seen.” None of which is necessarily new or risible, though it does beg the question: shouldn’t art also allow us to see other people?

It is an undeniable fact that Pound’s curiosity led him to some very curious places, and observing the pride with which many now habitually display their incuriosity through a defensive evasions or an affected jadedness, the most charitable reading I can give this is that they’re afraid of being compromised through an encounter with some corrupting element. Purity is a possession to be valued in the absence of others, which is why Pasolini believed it to be the lone asset of the sub-proletariat with nothing else to their name, and why unaccomplished youth tend to place a premium on it before they acquire the inevitable tarnish that comes from contact with the world. Some will even hang onto their sense of purity awfully late into life, something easier than ever to do thanks to the many marvelous buffers that technology offers against the world and its sullying compromises. This is probably why you tend to encounter so many paragons of perfect virtue in the virtual sphere, while IRL they’re curiously thin on the ground.

There is so much art we’ve been told we no longer need to “bother” with—though you could be forgiven for wondering why, if someone finds it such a bother to watch a film or read a book, they are writing about these subjects at all. The past is a problematic country: they do things toxically there. So neatly do the reformist dictates of ethical media consumption dovetail with the efforts of “content providers” to shorten our collective cultural memory until they only have to wait six months between reboots of the handful of remaining IP, if one didn’t know better you might regard the process as downright reactionary.

This closing off of the self from art and artists deemed undesirable, unsettling, or outmoded was confronted by Pasolini in his “The Poetry of the Tradition,” a plea for pleasure published in a 1971 collection titled Trasumanar e organizzar (To Transfigure and to Organize), addressed to the youth of a “Calvinist generation” who had become “hardened against anything that didn’t ooze the right sentiments” and “spent the days of [their] youth speaking the jargon of bureaucratic democracy never departing from the repetition of formulas.” In a particularly stirring run, Pasolini writes:

“The books, the old books passed before your eyes like the belongings of an old enemy you felt obligated not to yield to beauty grown in the soil of forgotten injustices you were in the end devoted to good sentiments against which you defended yourself as against that beauty with a racist’s hate against passion; you came into the world, which is vast and yet so simple, and encountered those who laughed at the tradition, and you took literally that mock-ribald irony, erecting juvenile barriers against the ruling class of the past, youth passes soon; oh unfortunate generation, you’ll become middle-aged, then old without enjoying what you had the right to enjoy and can’t be enjoyed without anxiety and humility and thus you’ll realize you’ve served the world against which, so zealously, you ‘carried on the struggle’: it was that world that wanted to discredit history—its; it wanted to wipe the slate clean of the past—its; oh unfortunate generation, and you obeyed by disobeying!”

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to Employee Picks, as that’s the only means I have to receive remuneration for researching and writing it.

Morrissey is not the only right-identified figure to have found something to admire in the Soviet Union; witness President Richard Milhaus Nixon, in a recorded conversation of May 13th, 1971, praising “the Russians” because “the root [homosexuals] out, they don’t let them around.”

Another Morrissey often regarded as a reactionary, former Smiths frontman Stephen Patrick Morrissey, was an avid Dolls fan, and dedicates a footnote to Paul M. in the 24-page chapbook that he wrote about the Dolls, published by Babylon Press in 1981. Just a few years later, Morrissey would choose a still from Paul Morrissey’s Flesh—depicting a shirtless Dallesandro—to decorate the sleeve of the Smiths’ 1984 self-titled debut LP.