The following is the first installment of a four-part piece discussing contemporary IRL livestreamers, the cross-breeding of cinematic and video game aesthetics, and various related topics. The following installments will post in intervals through 2021. Support and editorial advisement was offered by Aria Dean, Michael Connor, Anton Haugen, and Celine Wong Katzman at Rhizome, Andrew Chan at Criterion, and my dear friend, Justin Stewart. This piece was inspired by conversations with filmmaker and aesthete Michael M. Bilandic, who plays a small role in it, and grew out of two separate commissions from Rhizome and Criterion. The final result, which appears after approximately a year of writing and research, was something too sprawling and scurrilous to taint either upstanding masthead, so it instead emerges here with the generous sponsorship of Rhizome.

That jive jamboree at the U.S. Capitol in January, 2021 was yet far away when, on Saturday, September 12th of last year, the IRL streaming community got an anticipatory taste of national attention when a 28-year-old homeless YouTuber, Lifes Mavrek, alternately known as “Armando,” “Mando,” “Mondo, “Homeless Mando,” “Travelin Papi,” and “Salmon Andy,” livestreamed himself defecating in the driveway of the San Francisco home of speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. While IRL streamers—people who make an interactive sport of their daily lives by streaming and monetizing their mischief—count viewers and followings in the thousands while collecting revenue far out of proportion to those numbers, knowledge of their operations has remained largely unknown to all but the extremely online, particularly at the grotty, close-to-the-street level occupied by Mando, whose bowel dump sortie was circulated by deviant netizens with the hashtag #Poopalosi.

I didn’t prepare any Best of 2020 lists to summarize the cinematic accomplishments of last year, which newshounds may recall was marked by worldwide lockdowns and the dismantling of life as we’d known it, but if I had, #Poopalosi would’ve been a cinch to make mine, and for all I know more people saw it than anointed Best Picture Nomadland, because quite a few of us spent the last fifteen months extremely online.

It’s a small thing in the grander scheme, but among much else I will remember last year as the year that I became unstuck from contemporary cinema. This was, to some degree, a decision that was made for me—certain regular publishers of my writing ceased to publish regularly or at all, others pivoted to more extensive coverage of streaming releases and serial television, subjects in which I am unutterably disinterested. I did see a few films tagged as products of 2020 by U.S. release date, and a few of them—like Tsai Ming-liang’s Days, Angela Schanelec’s I Was at Home, But…, Bill and Turner Ross’s Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, and Paul W.S. Anderson’s Monster Hunter—I even liked a great deal, but once the final count had been tallied, there had probably not been a year since I learned to toddle when I saw so few new feature films. The sort of movies that I would normally have seen on the festival circuit I didn’t feel like watching in my living room, and a lot of them I didn’t really feel like watching at all. It’s possible this break is a temporary one, and a part of me hopes that it is, because I write about films for my daily bread, and even though I can eke out a subsistence living strictly engaging with movies that belong to the distant past of Before Times, I would like to believe that cinema is still a living art, and to stay savvy to where the life in it lies. Maybe I’ll play catch-up with last year eventually, and belatedly join my voice to the annual chorale of affirmation: “At a time when many have speculated that the death of cinema is at hand, the medium showed a surprising new life…”

Instead I passed a year, principally, in the weeds of film historical arcana. When I needed a shot of contemporaneity, I did a little monster hunting of my own in following the streamers, like Mando, or whatever he’s being called now. Contacted after l’affaire Poopalosi by the New York Post, Mando would frame his dropped deuce as an act of protest: “What better way to show someone the message, you know? We need more access to bathrooms, we need more access to resources out here.”

True enough, though any message was only incidental to Mando’s actual raison d’être which, like that of a great many IRL streamers, is to be a nuisance for the amusement of their at-home audience, egged on and rewarded for this activity by viewer donations, commonly referred to as “donos.” The announcements of incoming donos pop up in the chats that accompany livestreams on various platforms, along with a message from the “benefactor”—usually an encouragement, insult, or some manner of inflammatory gibberish. These missives are typically read aloud by a text-to-speech (TTS) program from a portable speaker mounted somewhere on the streamer’s person, often to incendiary effect, as online audiences tend to use this form of telepresence to escalate any developing situation at hand. Paying for the pleasure of broadcasting the n-word repeatedly via TTS is particularly popular; this is referred to as “the Keemstar dono,” named in dubious honor of Daniel “Keemstar” Keem, who today runs the YouTube gossip channel DramaAlert, his claim to posterity tied up with his groundbreaking petition to flood a chat with a certain epithet.

The IRL streaming community is comprised of a criss-crossing network of nomadic annoyances that includes defiantly unhygienic drifters, boy band burnouts, gamers-gone-wild, wannabe rappers, self-destructive alcoholics, methamphetamine enthusiasts, and alt-right famewhores, with a large percentage of identifiable sociopaths cutting through all these categories. I should add that there are very people using the IRL streaming form to create more socially acceptable or constructive content. I have not encountered these streams and, to be frank, haven’t sought them out, because the most debased form of the phenomenon is the one that seems to me to communicate something essential about the present moment. The IRL streamers I have become intimately familiar with represent the economy of internet clout taken to its most dissolute extremes, something like black sheep relations to far better-known vloggers and “YouTube personalities”—themselves not precisely a universally esteemed group.

These IRL streamers are, then, the underbelly of an underbelly, and in writing about them here, I’m abandoning my usual practice of using this space to pursue a criticism of enthusiasms. What this community kindled in me for the better part of a year would best be described as “morbid fascination,” and I can’t in good conscience endorse anyone going down the same rabbit hole that I squirmed my way into during this time, effectively playing canary in the content mines. I also can’t pretend that I didn’t find the experience occasionally enlightening and entertaining, or that, even while not having given one red cent in donos, that I remain unpolluted by my compulsive spectatorship. In any case, fair warning: Abandon Hope All Ye Who Enter Here.

BAKED

Whereas big YouTubers occasionally will “go live” on Instagram or Twitch, these interactive performances are part of a broader package of content; the IRL streamer, in the main, has only the golden shower of their stream to proffer, performances often disappearing after a short time or scrubbed from the internet in an attempt to destroy incriminating evidence, which lives on in diehard viewers’ archives of lowlight clips, found on message boards like ip2always.win, LiveStreamFails, and KiwiFarms. Where a Logan Paul or a PewDiePie may occasionally step in a cow pat of controversy, they generally attempt to toe a line allowing them to appeal to the broadest possible demographic, maintain their platforms, and keep their profits steadily coming in. The outlaw fringe of the IRL streamer community cater to only the most degenerate or the most based, depending on one’s perspective, and resign themselves to a peripatetic existence scampering from channel to channel and streaming service to streaming service, along the way snatching donos out of the air like banknotes blowing around a cash booth . Their independent bad behavior is part of an ongoing, kaleidoscopic drama of unbalanced, anti-social humanity run amok, with individual ronin streams running together and separating to form an insanely complicated narrative that puts the Marvel Comics Universe to shame.

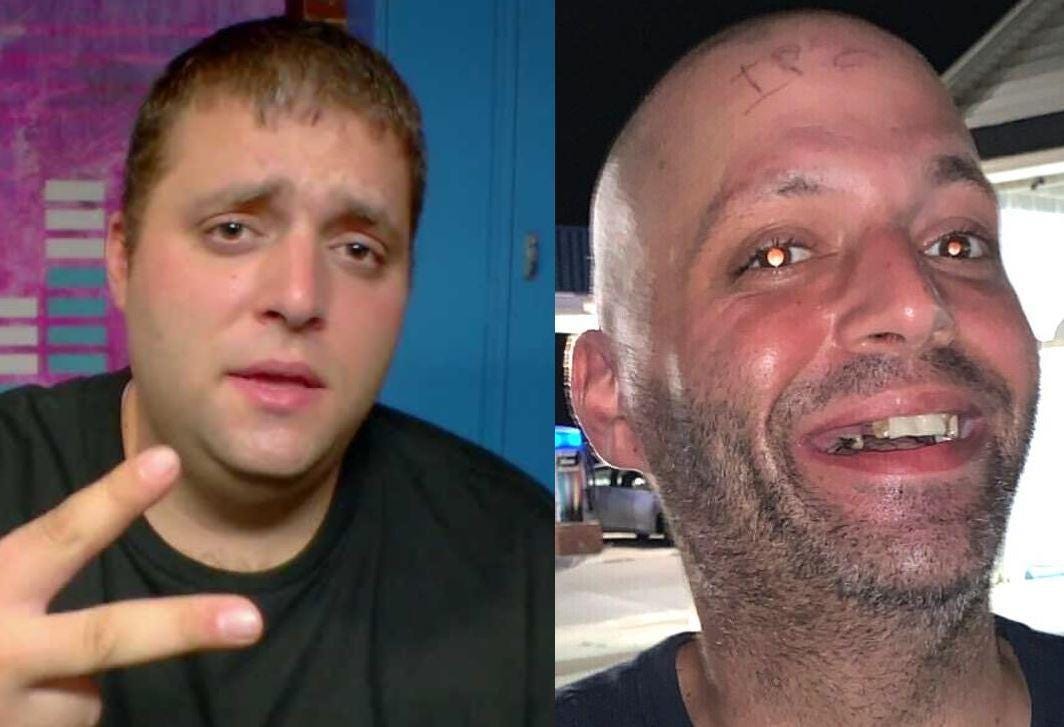

For example: Before his brush with politicized infamy, Mando, a husky Mexican-American with a patchy beard and a physique simultaneously looming and droopy, was best known as an associate of O.G. IRL streamer Ice Poseidon and the “friend” and personal assistant of pop star-turned-OnlyFans model Aaron Carter, who had housed Mando in exchange for YouTube consulting until December, 2019, when Carter kicked Mando out after he complained about Carter’s dog and made fun of his patron’s music during a stream. Having left his ordure in ‘Frisco, Mando proceeded to link up with Anthime “Tim” Gionet, better known as Baked Alaska, and they hit the road like the vaudeville teams of yore. Baked is a 34-year-old internet personality—the word is used very generously here—who has shown a barnacle tenacity in staying in the public eye. An Anchorage native, in his bygone youth he assayed a marketing degree from Azusa Pacific University into a Warped Tour internship and then a stint at Buzzfeed, where he ran the Twitter and Instagram accounts for Tasty, the site’s arm for food-related material. (He’d previously been a C-list Vine-maker, specializing in fucking with unsuspecting employees and customers at Targets and Whole Foodses and the like.)

Baked was first catapulted to minor notoriety around the time of the 2016 presidential election and subsequent media fracas over the land-rush discovery of the so-called “alt-right.” He was tour manager for a then-ascendant Milo Yiannopoulos and worked for “Gorilla Mindset” philosopher Mike Cernovich; racked up views on a video in which, after purporting to have been pepper sprayed (possibly self-administered) at the 2017 Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally, he was seen gasping “Keep streaming!” while on all fours with milk dripping off of his face; and scored up still more hits in another where he whines interminably about a woman breaking his “brand-new iPhone 7” outside of Playhouse nightclub in Los Angeles after his failure to respond to her request to stop taking video of her. Baked is compactly built, wears a bleach-blonde fauxhawk, a chinstrap beard that’s sometimes trimmed to a goatee, and signature nacreous Pit Viper sunglasses. He dresses for maximum visual noise, all bright colors and clashing patterns, with a particular predilection for camo and the American flag, and looks like a post-internet artist who went to MICA who you might find passed out in the corner at Rubulad in 2010.

Baked fell out of favor with Yiannopoulos and Cernovich not long after the land grab and cacophony of hillbilly elegiacs that followed the Trump election, and thereafter endured his wilderness years. He stayed in the picture as best he could through participation in the internet Bloodsports community—a loose confederation of “race realist”-leaning live YouTube debate channels, the most prominent of these run by Andy “Warski” Pires—and chameleonic attempts to rebrand, including a post-Christchurch mass shooting mea culpa and a stint with Yang Gang which may or may not have been a bit. He has since returned to the far-right fold, affiliating himself with the 22-year-old Nick Fuentes, a Bloodsports staple and fellow “Unite the Right” veteran who, via the streaming service DLive, which he founded after being barred from Twitch, addresses a steadily growing audience known as Groypers, named for an obese meme varietal of Pepe the Frog, seen smiling serenely while resting his chin on tented fingers. (After a slow start, Fuentes’s DLive sermons today reach upwards of 50,000 viewers.) Baked’s journey has been documented via his IRL livestreams, which began sometime around 2017, but snowballed in popularity via association with Fuentes and the organization America First Students. Last year Baked became nigh ubiquitous, to the chagrin of many in the livestreaming community who view him as a roving opportunist. His 2020 motto was the MAGA-esque initialism YOBA—“Year of Baked Alaska”—which he could be heard chanting while capering around in the office of Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley on January 6th, for it appears YOBA didn’t end with the calendar year. (Fuentes was also on the ground in D.C., but denied claims that he entered the Capitol.)

During the buildup to the presidential election, Baked continued to practice a proven formula for content generation that he didn’t invent, but excelled at: aggravating people, creating and escalating tetchy social situations, and generally keeping the trolls and lols coming. In the lingo of IRL streaming, this is referred to as “pressing”—basically, pushing someone’s buttons—until they blow their lid and start acting the fool, with whoever comes off the worse in the resulting conflict said to have been “maxxed out.” This, of course, is where the fun, such as it is, begins.

In 2020, the mask protocols demanded by many businesses provided a lubed-up opening for many a press, retail workers being favorite targets as they aren’t at liberty to walk away from the source of ire: see for example Baked and Mando at a Burger King stop during their odyssey, where, after refusing an employee’s request that he mask up, Baked is escorted out while gleefully calling the staff “slaves” and “NPCs” for trying to enforce company protocol as Mando plays conciliatory good cop, explaining to a worker in a “Flame Grilled Living” t-shirt that his partner is “Asperger’s high-functioning.” At this point Mando and Baked are still performing their double-act from the same script, but the bonhomie doesn’t last long.

In another road trip video, Baked and Mando sit together at a Wendy’s, Baked bouncing in his chair and doing a hyperactive fist-pumping dance across the table from a visibly agitated Mando who sits, head down, trying to block out his partner’s shenanigans. A middle-aged female employee arrives to ask the two to leave, and as she does, Baked cranks a tune on the portable speaker attached to the strap on his backpack, which contains the cellular transmitter essential to streaming. The song is “Nigga Nigga Nigga” from the 2007 film Gangsta Rap: The Glockumentary, and mostly consists of the title being repeated in a rat-a-tat cadence. (Had his TTS been turned on, we very likely would be hearing the same thing with a hard-r.) Baked, incidentally, was formerly a comedy rapper: he started out doing Alaskiana numbers like “Grizzly Bear Trappin’,” in 2016 recorded an unlistenable “MAGA Anthem,” and continues to issue the occasional ballad, doing to the eardrum what Mando did to the Pelosi driveway.

Baked enjoyed a rapid rise in IRL streaming, but it’s hard to say what percentage of his viewers are only hanging around to see their favorite lolcow—that is, a dull-minded herd animal who serves up rich Grade A creamery content, oblivious or indifferent to the fact that they’re being milked for laffs by fans who loathe them—receive his comeuppance. He is routinely pilloried on message boards as an arriviste, a slippery mountebank who adopts and abandons trends or, as one boarder put it, “a doxing faggot that purposely is trying to destroy this community whilst he is slapping and hitting women.”

A man with a Houdini-like ability to slips cuffs and evade arrest, to the joy of many onlookers Baked went to the pokey last December after twice Macing a bouncer outside Giligin’s Bar and Shrimp Hut in Old Town Scottsdale, Arizona. Jubilant commenters who’d been waiting for the man they loved to hate to take a fall could be seen bemoaning the fact that Maricopa County sheriff Joe Arpaio’s seven-acre “tent city” jail was no longer in operation. Baked, who last year released a heavily Auto-Tuned song called “We Love Our Cops” and accompanying music video, gave off a “Fuck the police” for the camera as the sirens flashed. You should watch it only if you’re looking for reconfirmation that we are all actually in Hell already, nostrils plugged with the acrid stench of Flame Grilled Living.

ORIGINS

Modern, vocational IRL streaming, as practiced today by Baked and Mando and many others, has its origins in livestreaming video games. Inasmuch as any original genius of IRL streaming can be identified, it is Ice Poseidon, formerly known as Paul Denino, spoken of in hushed tones as the first gamer to emerge blinking with his camera into the light of day, like that first fish struggling from the brackish sea onto the primordial Pangean shore. Denino, a native of Martin County, Florida born in 1994, started using his nom-de-stream when he was twelve years old and an ardent player of the online role-playing game RuneScape. The RuneScape community remained a central element of Denino’s social life—very possibly the central element—after he graduated high school, and while working as a line cook, Denino began to upload videos of his RuneScape prankery onto YouTube, operating a livestream on Twitch where people could watch his gameplay and goofing and building a community of viewers who became known, somewhat ominously, as the Purple Army.

The inspiration to take his stream—and the Purple Army—out of the proverbial parental basement came in July 2016, when Nintendo released Pokémon Go, an augmented reality (AR) product that gave a real-world dimension to its gameplay. To capture and train Pokémon, players would follow a GPS-generated game map based on their surroundings to PokéStops and Pokémon Gyms, their on-screen avatars following their real-world peregrinations. And so, as the legend has it, before heading out to scour the plentiful surface parking lots of Palm Beach for Bulbasaurs and Snorlaxes, Ice Poseidon strapped a webcam to his head, thus giving birth to modern IRL streaming. Denino, a scraggly, lemur-eyed, high-energy ectomorph with an unexpectedly gruff baritone, wasn’t the first human to stream out-of-doors, but he had malevolent charisma enough to build an ever-larger community around himself, and more than any other person can be looked to as IRL streaming’s Founding Father, or Original Sinner.

Was 2016-17 the moment when IRL and the internet began to converge once and for all? The argument can be made. At the time my friend Michael Bilandic, a filmmaker and cogent thinker on all things online, was keeping me breathlessly posted on the saga of Shia LaBeouf, Nastja Säde Rönkkö, and Luke Turner’s insipid post-2016 election installation work HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US, comprised of a publicly displayed camera with the words “He Will Not Divide Us”—the “He” referring to you-know-who—written above it, with passers-by encouraged to voice this phrase to an audience watching via 24/7 livestream.

Instead of a rallying point for its inscribed #Resistance audience, the camera became a magnet for interloping Trumpists, right-wingers of all stripes, and various bored shit-talkers. Initially set up at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US was moved repeatedly to avoid unwelcome attention, all to no avail. Removed to a nondescript “unknown location” in Greenville, Tennessee, accompanied now by a flag emblazoned with the title of the piece, HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US was discovered in less than two days by 4chan users taking note of airplane contrails and celestial navigation—some of the same swift-fingered researching that would later be turned to doxxing IRL streamers like Ice. If the intention of LaBeouf and company had been to bring every crackpot in America out of the woodwork, it must be judged a thumping success—and having had a lungful of fresh air, the freed genie disdained its old bottle. Baked caught up with HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US in Queens, where he can be seen on video pressing a security guard until he threatens to smash Baked’s camera phone, which as you can imagine happens a lot.

As r/The_Donald posters and idle neckbeards chased an empty-headed piece of protest art born of a celebrity’s vanity gallery career across the United States and Europe, Ice Poseidon continued to rack up spectacular metrics. In summer of 2018, Denino, who had relocated to Los Angeles during his rise to power, was the subject of a New Yorker profile by Adrian Chen. The piece describes Denino’s cultivation of a “foulmouthed trickster” character—like a modern-day Loki or Kokopelli, one supposes—pressing his way around the globe. Chen also outlines the occupational hazards of livestream celebrity, which include the loss of privacy and the occasional “swatting,” in which a livestream viewer possessed of the streamer’s address or location will place a false report of some hazardous situation unfolding at the scene, resulting in the SWAT team kicking in the streamer’s door, to the onlooking culprit’s delight. Chen’s profile also notes that at the time of the author’s meeting with Denino in January, the then-23-year-old was set to earn $60,000 in a single month.

Quite understandably, in the wake of Ice Poseidon’s breakthrough, his formula for success spread like kudzu. Like a water-soaked Mogwai, Ice Poseidon reproduced Gremlin imitators wielding selfie sticks, wearing nattering speakers and, in many cases, looking for novel ways in which to be bothersome.

The rewards were potentially great, the investiture slight. If you want to be an IRL streamer, first you need a camera. This will likely be a smartphone, with the Samsung S9 and S9 Plus series, as well as Galaxy S10 and S20 variants particularly popular, though some opt for a dedicated camera like the GoPro Hero 7 or the knock-off EKEN H9R or a nice Sony AS300 Action Camera. You may then throw down for various mounts: a nice selfie stick like the Smatree SmaPole Q3S, a gimbal mechanical stabilizer, or perhaps a backpack mount to free up the hands. And you will most probably be wearing a backpack—the Gunrun.tv packages custom-made jobs—to house all the odds and ends that will keep you online, including a power bank such as the 26800 mAh Anker, which provides a day’s battery life on a four-hour charge. You can trust to the omnipresence of Verizon for an uninterrupted stream, and many do, but the true professional may also invest in their own mobile hotspot, such as the Netgear Nighthawk M1 or LiveU Solo HDMI. Streaming to Twitch, YouTube, DLive, or another platform of choice—or necessity—is accomplished through a streaming and recording program, OBS Studio. The chat platforms and payment plans are provided by third-party live-streaming software, the most popular of these being Streamlabs, Donationalerts, StreamElements, and Nightbot, which allow the streamers to cash in their donos—part of the reason Androids are preferred is because they handle multitasking, particularly with the chats, better than the iPhone. Finally, to receive incoming sound alerts, you’ll want a small Bluetooth speaker, something like a JBL CLIP 3 or the WONDERBOOM 2, recently endorsed by the New York Times, that will keep the lively TTS palaver chirping away.

With this initial investiture paid in, a flotilla of IRL streamers with colorful sobriquets were unleashed upon the world. There was Bjørn Lisdorf, a Dane who’d gained a Twitch following by playing Entropia Universe. Recently unemployed in his home country and inspired by Ice Poseidon’s newfound prosperity, Lisdorf travelled to Los Angeles with the zeal of a convert tracking down the Nazarene and, adopting the mononym “Bjørn,” he’s remained a power player since by virtue of his ability to generate the rancorous rivalries and drama that are dono paydirt—a comparison to hyped-up, trash-talking pro wrestling feuds would not be inappropriate.

The IRL streamers produce more beef than the state of Texas. Bjørn was for a time quarreling with Ebenezer Lembe, aka EBZ, a fortysomething former Uber driver from Cameroon drawn into the fold after meeting Ice Poseidon on the job. EBZ, reliably press-able, also had a high-publicity clash with Billy the Fridge, born William Berry, a hulking white rapper from Seattle who when he first appeared on the scene was pushing 700 lbs., though he has since slimmed down considerably. Beneath marquee names such as these you found the character actors, the Andys—Arab Andy, Asian Andy, Mexican Andy, Tracksuit Andy and, foremost among them, Andy Milonakis, aughts-vintage viral sensation-turned-star of MTV’s The Andy Milonakis Show, white rapper (are you sensing a pattern?), and a former Ice Poseidon associate. Milonakis blew up as a streamer after showing up on Ice’s feed, and anyone who followed the same route thereafter was dubbed an “Andy.”

Reps are built through these acts of “stream sniping”—unknowns finding the location of established IRL streamers and just turning up there, sometimes just hoping to hitch their trailer on a star and siphon off a few viewers, sometimes looking to cause trouble like young bucks in a Western looking to make a name by plugging the fastest gun out there, which I guess would’ve made Ice, for a time, John Wayne in The Shootist (1976). Or perhaps they could better be compared to pugilists chasing a belt—and internet clout has even infected the tradition-bound world of the Sweet Science, as an untested club fighter like Logan Paul, by virtue of name recognition alone, was until recently cleared for a shot at the undefeated Floyd Mayweather Jr.

This ever-more-populated cast of characters has been tracked and discussed on the various abovementioned message boards—after a 2019 reddit ban of communities dedicated to IRL streamers, the subreddit devoted to Ice, r/ice_poseidon, became IP2always.win—the “IP” stands for Ice Poseidon, though any affiliation with Ice, now a bête noire of the board, is long over. Such Oedipal relationships are not unfamiliar—I spent a chunk of the ‘00s on Hipinion, formerly the official message board of Pitchforkmedia, which after being removed from the site became a popular destination for people looking to make fun of the picture of Pitchforkmedia founder Ryan Schreiber as a podgy pale teenager in suburban Milwaukee wearing a Pac-Man t-shirt and sporting an ill-advised pink New Wave-y hairdo.

The distance from throne to pillory barrel is very little online. As the IRL streaming scene grew in popularity, Ice, indisputably the central figure of the community’s early years, began a precipitous plummet, this triggered by the failure of his attempt to create a mansion for the confederation of streamers admitted to his CX Network and the shutdown of the network itself in March of 2019 following an FBI raid and seizure of Ice’s streaming equipment, after which a chastened Denino fled from Los Angeles to Austin. Along with other unsavory tech types the Texas capital has become a streamer haven, home to many of the most feral of the breed of unsavory tech types, for generally streamers prefer warm weather climes that favor year-round street life and ample possibilities for pestering people.

Ice’s decline left a vacuum as his CX Network begat the IP2 Network, inheritor to a certain tradition of scumbag streaming, which various tenable successors have emerged at the apex of: Bjørn, the infamous ONLYUSEmeBLADE and, last year, Baked, who rode election-year action and an open defiance of the pandemic-era stay-at-home advisements heeded by some skittish streamers to his YOBA putsch. The Capitol crash was followed by an Elba exile, but as to if he has yet met his Waterloo remains to be seen.

A STREAMER’S QUALITIES

If the new mobility of the IRL streamer was a departure from the trail blazed by the indoors streamers of yore—Ice’s travels included a European Grand Tour of a sort you’ll find in no Baedeker—the phenomenon of hustlers and exhibitionists building an audience by offering an unblinking vantage on their lives is not. Chen finds a precedent for the IRL streamers in the “lifecasters” of another era, citing the case of Jennifer Ringley, the Dickinson College junior who in 1996 installed a webcam in her dorm in Carlisle, Pennsylvania and broadcast images of her mundane life—black-and-white, updating every three minutes—through her JenniCam website.

While JenniCam and its imitators certainly have their place in streaming history, one key element of their appeal—the possibility of intimate disclosure of the female body in a domestic space—makes them seem nearer ancestors to the now professionalized, nay, industrialized, and largely housebound occupation of the camgirl. (There are those in this line who specialize in public stunts like surreptitiously sticking a dildo in their asshole while seated in the back of a Panera Bread, but they are outliers.) What is missing in this linkage are the elements that mark IRL streaming in its more extreme, and therefore more visible, manifestations: masculine debasement of self and others, and general public inconvenience.

The IRL streamer is a new breed of flâneur, though rather than following Charles Baudelaire’s exhortation to “wed the crowd,” he—and it usually is a “he”—prefers to assail it, antagonize it, and molest it. Some other precursors suggest themselves here: There is George Urban, better known as Ugly George, famous for his misadventures on his Manhattan public-access cable show The Ugly George Hour of Truth, Sex, and Violence, which would document his roving the canyons of Midtown, buttonholing women and trying to induce them to unbutton before his camera. There is also the Jamie Gillis of the On the Prowl series, begun in 1989, the first of which follows Gillis and porn actress Rene Morgan as they cruise around North Beach, San Francisco in a limousine looking for strangers to plow Morgan. (Five attempt to push rope; two succeed to the point of vaginal penetration.) From here it’s a short leap to Joe Francis’s Girls Gone Wild tapes, and to countless other gonzo frolics.

These comparisons, too, are slightly shaky, not least because sex, for some time anyways, remained a department of transgression that IRL streamers ventured into least often. There are exceptions to this, but even these favor emotional terrorism and debasement to what most would regard as titillation, as when Attila Bakk, aka Attila, a Hungarian-born streamer originally based out of Windsor, Ontario, did boffo metrics last November through drunkenly denigrating a sex partner, fellow streamer Jewel Rancid, on- camera, afterwards reading vicious chat comments aloud while she could be heard vomiting off-screen. Later, after Rancid has passed out, Attila, who has the visage of a depraved imp, indulged in a to-webcam monologue that begins with a bellowed “You will never get this lifestyle,” continues through his confronting in the nude a complaining neighbor who comes to his door, then ends in a barrage of n-bombs. Insofar as can be determined, this is the couple’s idea of a good time, and there is some evidence that Rancid, who pads her income selling mayonnaise fart videos online, has an insatiable appetite for humiliation—none of which is to say that this activity, to whatever degree it can be judged consensual, is “good” for anyone involved. Just in time for Christmas last year, Attila and Jewel released a single they’d recorded together, a Human League-ish pop tune called “Leaving Town,” whose chorus goes: “Leaving town/ Gonna do it/ Blowing loads/ Making movies.”

It’s not hard to explain the relative paucity of sex in IRL streams. Homosocial as the scene may be, homosexuality is officially abhorred—damning rumors of a relationship between Fuentes and Australian streamer CatboyCami continue to swirl—and there are not so many female streamers willing to roughhouse with the boys or subject themselves to the pitiless scrutiny of the stream: the unflattering screenshotting and the inevitable meme-ification. (Chen documents that communal outcry surrounding Ice Poseidon’s relationship with a fellow streamer, Caroline, “broken up” by a concerted and seemingly successful attempt to hurt him by cutting down on his donos.)

To the dismay of many, including a quite vocal Ice, Twitch has had a steady uptick in female streamers, many of them appearing on the site’s non-gaming “Just Chatting” section. The objection to “titty streamers,” so-called, is frequently expressed as a desire to prevent what has long been perceived as a haven for mostly male gamers from becoming a camgirl site, an inevitable de-evolution into fawning and simping to be anticipated once the fairer sex appear on the scene. Many women have nevertheless commanded large followings on Twitch and other streaming platforms, but the likes of Cal Poly student Maya Higa, who leveraged her following to raise $32,000 for local homeless in May of 2019, is not likely to appear in the same stream as any of the roving footpads and highwaymen that I’m discussing. Those that do—women with monikers like Goocheese, Sweet Erin, Alice, and Sammy figure in the unfolding drama—generally don’t last for long, and when they do, they do through exhibiting a sponge-like ability to sop up punishment. The IRL streamers of IP2, then, provide an alternative to an ever-more-feminized Twitch, a “No Girls Allowed” zone in which any mitigating or civilizing influence from the fairer sex that might hamper the pursuit of pure lulz is kept to a minimum.

Content generation by way of pressing, from the days of Ice Poseidon on down the line, is based in brazen harassment and intimidation, and I don’t think it’s too bold to claim that this is a field in which the male of the species excels. One might place the IRL streamers in a tradition of overwhelmingly male prank culture that includes Longmont Potion Castle crank calls, the output of Nathan Fielder and Sacha Baron Cohen, parody meme accounts, and Jackass’s hidden-camera forays into the public sphere. (Recently there has been an attempt by some boarders to pull the troubled Bam Margera, disinvited from the shooting of Jackass 4 due to unaddressed drug abuse issues, into the orbit of IP2.) A prank divides the world between “us” and “them”—those who are in on the joke and those that aren’t—or, in this case, those who are doing or watching the streaming and the civilians who are caught up in the stream, deer-in-headlights style. For a Baked, the Other is identified with familiar messageboard troll slanders: cucks, SJWs and the abovementioned NPCs, short for non-player characters, a term adapted from tabletop role-playing to video gaming. An NPC isn’t controlled by the player, but rather following a Dungeon Master’s whim—Soros, I guess?—or a programmer’s script and cues. The player has free will and agency; the NPC does not. As a way to designate humans who are not regarded as fully human, it seems to have overtaken the previously ubiquitous “sheeple” in popularity.

Between the various prank artists I’ve listed there exist vast differences in approach, in wit and conceptual intelligence, and in the attitudes evidently held towards their unsuspecting quarry, with the IRL streamers unquestionably the stupidest and the cruelest of the lot. And yet, what they do does exert a discomfiting fascination, for it delivers something of the Shock of the New, and this bears description. For none of the above comparisons, from gonzo to Steve-O, can boast of the interactivity of the IRL stream, nor of its simultaneity, and the total unmediated unpredictability—and the air of potential danger—that comes with it.

Ugly George and Jaime Gillis, of course, have the option of editing what they’re doing after the fact in order to make themselves look better or to move a scene along—though if either did much of the former, whatever was left on the cutting room floor must really be something to see. The IRL streamer is either off or on; watched in the present tense, their missions of mayhem are interrupted or compressed by no ellipses, and by no moments of respite. Simultaneity removes any sense of foregone conclusion from what we’re watching. If Cohen had happened to have been blown away by an incensed concealed-carry type while out making mischief in his Borat togs, one imagines we’d have heard about this before seeing it, if see it we ever did. The outcome of the IRL livestream, however, is undetermined. And if one peruses the chatrooms and message boards dedicated to IRL streamers for any amount of time, it becomes evident that a large part of the attraction to these streams is the anticipation, even the expectation, of seeing someone die in real time.

This suggests another antecedent for the IRL streamers: that of blood sports, of the Circus Maximus, of the fairground attraction. In Death Riders, a gorgeous, rambling 1976 documentary about young, fearless itinerant stunt performers making their way across the U.S.A. doing motocross jumps and controlled car crashes, you can hear the troupe’s announcer expertly whetting the audience’s appetite for destruction before each act: “He has been cut out of many cars while the car is still on fire, so… anything can happen,” “Two sticks of 60% dynamite is placed eighteen inches from his head… He may not even walk again, he may not even breathe… He could be killed doing this act.” This combination of threat and promise is key to the ballyhoo of the IRL stream. A poster on KiwiFarms describes a fantasy that’s by no means unusual: “I hope Baked gets capped in one of these streams… The stream would be Kino.”

MAKING KINO

The term “Kino,” Russian for “cinema,” is a redditor shorthand for high-brow cinema, as differentiated from the sort of things the plebs and NPCs go in for. It conjures up the Kino-Pravda newsreels of Dziga Vertov and his Kinok collective—as the Russian Civil War raged, Vertov ran a film-car on Old Bolshevik Makhail Kalinin’s agit-train which allowed the Kinoks to shoot, develop, cut, and project films as they traveled the country, in the process recording revolutionary history, as nearly as possibly, as it happened.

The agit-train, and Vertov’s subsequent filmmaking activities, may be counted as one attempt to resolve a problem that has frustrated many a cineaste through the years: to close the gap between cinema and events, which are forever moving ahead and just out of reach, and to bring forth a cinema that has the same potential for unrehearsed spontaneity as life itself. Vertov sought a new kind of filmmaking that would capture “life caught aware,” which could be practiced quite literally—he was not averse to the usage of hidden camera—but also denoted a practice of sneaking up on life, of recording what happened through life’s sudden confrontation with the camera, a kind of ambush.

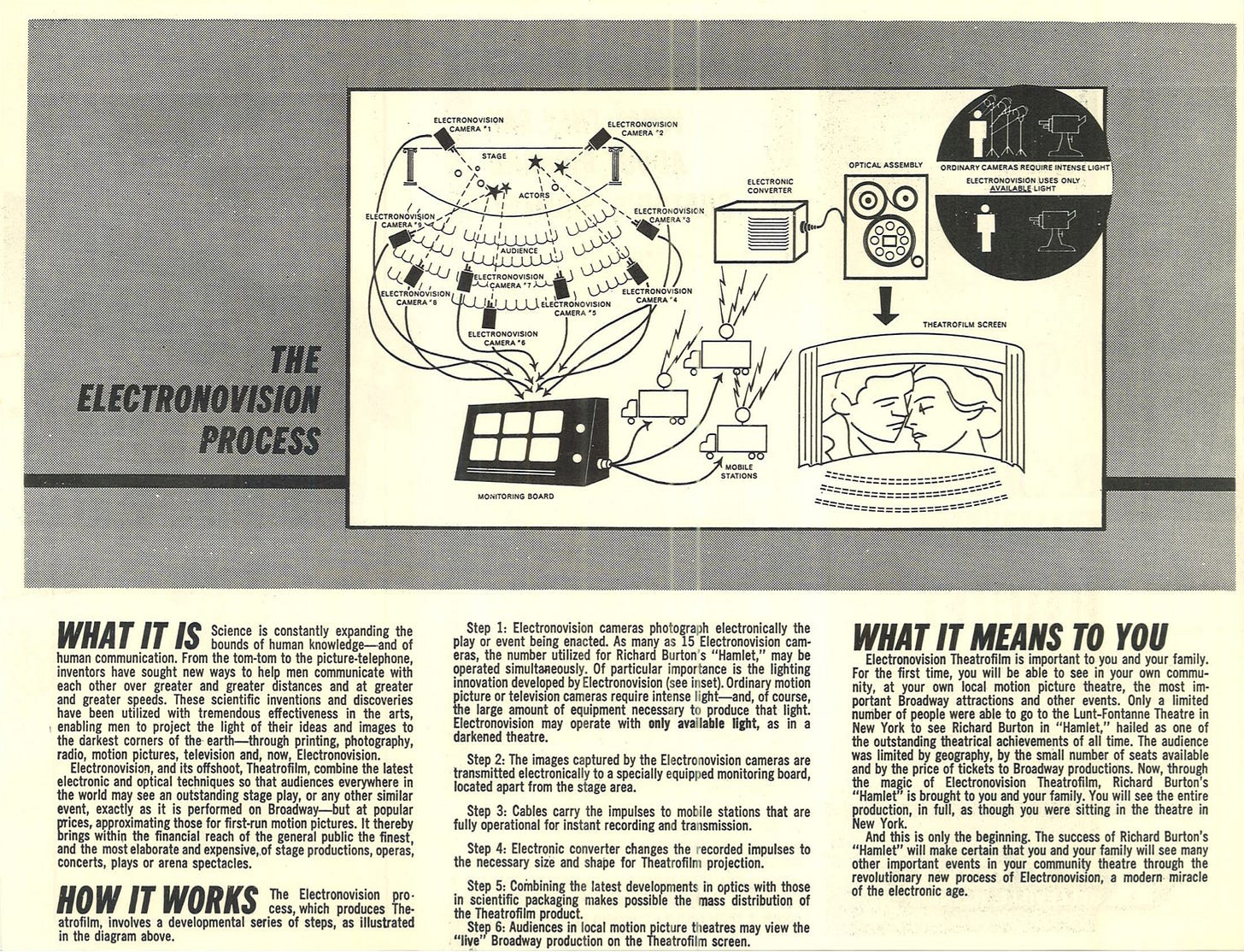

Fresh hope for the prospect of a “live cinema”—if we think of cinema as bound up with theatrical exhibition, as people did for much of the lifespan of the medium—came with the appearance of broadcast television, transmitted live in the early years of TV, but for decades the concept of live cinema was not much further developed. With the advent of video recording, live television became largely the provenance of news and sports, and movie theaters’ dependence on celluloid projection scuppered the possibility of broadcast simultaneity. There were attempted exceptions, like producer William “Bill” Sargent, Jr.’s Electronovision process, in which performances were shot live and edited on the fly in the fashion of live television productions before being transferred to film for theatrical exhibition, but “prepared” cinema remained the rule.

Electronovision, which promised to deliver something of the live-wire thrill of Richard Burton in Hamlet or James Brown and the Famous Flames on the T.A.M.I. Show (both 1964), essentially invented the template for the NCM Fathoms “events” of today. The Fathom simulcasts of KISS concerts and The Metropolitan Opera were made possible by the 21st century digital changeover, in which DCP overtook 35mm as the standard for theatrical projection, an event which has reignited the dream of live cinema in some bosoms. Francis Ford Coppola, a great enthusiast of the live broadcast productions of television’s Golden Age, conducted two “experimental proof-of-concept” live cinema workshops in 2015 and ’16 at the Oklahoma City Community College and at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film and Television, and wrote of his experience in a 2017 book called Live Cinema and Its Techniques. Coppola imagines “live cinema” as a work that would combine the living-and-breathing immediacy of theatre and live television with the deliberate and variegated shot selection of cinema, achieving “a cinema-like expression which required that the shots not just be coverage, but real building blocks in the cinematic telling of the story.”

In his book, Coppola recounts accidentally getting stoned on the rock promoter Bill Graham’s marijuana butter cookies at the 1979 Academy Awards before taking the stage to present a Best Director statuette to Michael Cimino, taking the opportunity to make a messianic prediction of the coming of a “communication revolution that is about movies and art and music and digital electronics and computers and satellites and above all, human talent [that is] going to make things that the masters of the cinema, from whom we have inherited this business, wouldn’t believe possible.” Coppola goes on to describe his own failed revolutionary undertakings: a catastrophic live television event for California Governor Jerry Brown’s 1980 presidential run, and the ultimate decision not to shoot his 1982 One from the Heart in the fashion of a live, multi-camera, one-shot television production, deterred by his cinematographer Vittorio Storaro. Still struggling with the problem of live cinema into his eighties, the fading Maestro has words of praise for Woody Harrelson’s contribution to the medium in Lost in London, which he calls “a Milestone in the history of Live Cinema.” Screened live in some 500 cinemas on January, 2017, Harrelson’s directorial debut, in which he stars as himself, is a single-camera, single-take caper, loosely based on a run-in with the London police that Harrelson had one night in 2002.

Police encounters are regular a staple of IRL streamer content, but there has been little to suggest aesthetic ambitions or foresight on the level of Coppola’s or Harrelson’s, and as close as streamers have come to tackling traditional cinematic exhibition was an Ice Poseidon event announced last December at the flagship Alamo Drafthouse in Austin—which ended, predictably, in a shitshow. If the IRL streams are live cinema, they are live cinema of a different category than any imagined by Coppola who, for all his farsighted futurism and undimmed belief in the potential of technology to transform and evolve cinema, doesn’t seem to have imagined the phasing out of the role of directorial authority and discretion in imagining cinema’s future.

I suppose that no-one anticipates their own obsolescence, any more than they do their own death, least of all a megalomaniac who can still recall being the conquering hero of New Hollywood, issuing orders to a squadron of attack helicopters in Philippine airspace. But we are now a lifetime away—my lifetime, in fact—from the world in which Coppolas and Ciminos had that kind of weight to swing around, and if there is to be a renascence of live cinema, there’s not much reason to expect that men or women of their ilk will direct it, or even to expect that it will be directed in any recognizable sense at all. Did you know that Francis Ford Coppola published a book in 2017? How many people do you think did?

LOST IN AMERICA

While Pokémon Go brought streamers like Ice and his imitators out of their bedrooms and basements, the COVID-19 pandemic and widespread self-quarantining that followed it briefly appeared destined to drive them back in. This was the case for some, reduced to the IP2-disdained “desktop streamers,” aka Desktop Andys, but certainly not all, and those who remained in the streets, like Baked, reaped the rewards of more-than-usually captive audiences.

IRL streamers are drawn, as moths to the flame, to events of any kind—rallies, protests, riots, the Los Angeles Lakers winning the 2020 NBA Championship—and in the year of lockdown the streamers offered one window on spasms of unrest around the country, and other curious sights besides. In April, Captain Content, a Spanish-born IRL streamer, could be seen wending his way through an anti-social distancing protest in Nevada, his TTS brightly nattering “Fuck Trump supporters, you are all pussies.” As protests and unrest in New York welled up in response to the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, on June 3rd, 2020 you could see 18-year-old YouTuber Malik Sanchez, aka Smooth Sanchez, wandering through the West Village and vicinity of Union Square, accosting mostly white passers-by, identifying himself as being in the employ of “the CEO of Black Lives Matter,” and insisting that his marks “Take a knee for George Foreman,” in some cases asking them to apologize for their white privilege after kneeling. At first several blow by, and are berated by Sanchez for doing so, but then he hits a streak, and one pedestrian after another concedes to solemnly kneel on the sidewalk at the edict of the CEO of BLM in tribute to the inventor of the Foreman Grill, still very much alive and probably capable of KOing Logan Paul.

An outraged Tucker Carlson showed a clip of Sanchez’s stream on his program as an illustration of bullying mob mentality run amok, demanding “the atavistic ritual of self-abasement” like an occupying army gloating over their conquest. Dmitri Solzhenitsyn, writing in the National Review some days later, gleaned satirical intention beneath Sanchez’s self-described trolling, opining that Sanchez had unmasked a cultish aspect in the contemporary liberal imagination, through his stream showing people who “have transcended the material plane and reached a level of mystical elevation in their political fervor,” for whom “the woke genuflection of repentance is like unto a kneeling prayer.”

Presumably Carlson and Solzhenitsyn—grandson of the author of The Gulag Archipelago—mean what they say, whatever one happens to think of it. The ideology of the IRL streamer troll is more difficult to pin down, and deliberately so. Many are frankly apolitical; some, like Trumper-baiting Captain Content, ostensibly gravitate leftwards; others, like Baked and Sanchez, ostensibly skew right, though one can’t imagine the buttoned-down respectability conservatism of Mitt Romney and company much appealing to their sensibilities. The IRL streamer phenomena corresponds almost exactly to the Trump era and the troll culture concurrent to it, and Trump’s preternatural ability to press and trigger seems to have provided many a streamer a guiding light—as Norman Mailer wrote from the 1972 Republican convention, the presidency is “a primitive office and inspires the tribes of America to pick up the modes and manners of their chief.”

The invincibility of the troll springs from the troll’s total mutability. Because there is no core self to protect, attack and offense can be adjusted freely to the needs of the moment, to best bedevil the individual being dealt with. The pose of victim is blithely adopted when convenient, discarded just as quickly. In a much-circulated stream from early last October, Sanchez, a hobgoblinish Latino kid with an overbite who looks like he weighs 110 lbs. soaking wet, gets in an altercation with a man in line outside of a California Donuts location—this was part of a much-touted trip to Los Angeles—which ends with Sanchez Macing the man repeatedly, to little visible effect.

Sanchez is with two compatriots, one of them the Austin-based IP2 streamer SCJ—the initialism stands for “Scuffed Jim Carrey.” (“Scuffed” is a terminology from the Ice Poseidon days, referring to Ice’s derelict, careless lifestyle, which has become as much an intrinsic part of the streamer aesthetic as extreme asceticism was to the Bolsheviks.) When the man, who they for some reason have begun to identify as “David,” makes a comment about SJC’s mother, he responds “My mom’s dead… My mom died fighting for this country… My mom’s a patriot… My mom got a Purple Heart.” Sanchez and SJC pelt “David” with a stream of “Faggots,” and when he then responds in kind, SCJ bounces back with a mock-offended “I’m gay, bro, by the way—I’m bisexual… Look at you, bullying a bisexual autistic man.” Sanchez and SCJ repeatedly identify themselves as “17-year-olds,” which they are not, presumably with a view to making “David” believe he would face charges for assaulting a minor if he responded to their three-on-one provocations with fists. And as Sanchez, SJC, and their third, Jacob Zone, unseen because he’s filming the action, pile into their car to beat a giggling retreat, who should be there in the back seat but Baked himself.

It is hard to overstate just how relentlessly negative all of this is, so much so that anyone participating in this attention economy must presumably cease to register the negativity as anything other than room tone, a dull buzz, the mephitic natural state of things. While Sanchez and SJC pelt “David” with abuse and he returns fire—not nearly so adroitly, it needs be said—the comments section in turn scrolls by seething with all kinds of omnidirectional abuse: for the cucked “David,” for Sanchez and SJC, even for the widely loathed streamer ONLYUSEmeBLADE, who’s nowhere to be seen. Opines one Ric Flair, “pretending to be kids to protect yourself might be the most pathetic thing I’ve ever seen.” Pretty noob comment, honestly. What Sanchez and SJC are doing is par for the course: the bad faith exploitation of grievance politics, used for the loopholes they offer that facilitate evasions and “Get Out of Jail Free” card escapes. The troll streamer’s one true creed is content at any cost, be it through burlesqued cries of victimhood or a well-placed Keemstar dono or twenty.

Later in October Sanchez made the news again, arrested after climbing to the top of the Queensboro Bridge. In the video from his stream, which is still online (TK), he can be seen clamoring up the struts and sway bracing on the north side of the bridge over the Roosevelt Island Tramway, from which position he squirts Mace down towards pedestrians passing on the walkway below, hollering “How does the jizz feel?” Someone called “Dickhead” tips Sanchez $2.00, this accompanied by a request to “Shit in your hand and drop it on someone,” which Sanchez declines to do. All of this is relayed via Sanchez’s TTS which is set up to speak in a clipped and very civilized English accent, pronouncing “Faggot” as “Fay-get.” When the police finally arrive, stopping traffic to question Sanchez from below, they ask for identification, to which he answers: “SMOOTH SANCHEZ, CONTENT KING!”

PRESS OR BE PRESSED

This drive to self-publicize is not a new development in the life of this fame-hungry Republic. In 1886 Manhattanite Steve Brodie gained instant celebrity by claiming to have jumped from the Brooklyn Bridge, and assayed his fame into a saloon on the Bowery, and it is not too much to imagine that had he the equipment available, he might have done the jump with a GoPro in tow. When drama is lacking, it is the sworn duty of the streamer to provide it—to press or be pressed. This tendency is elevated to pure grotesquerie in Eugene Kotlyarenko’s 2020 film Spree, a sort of social media- age Taxi Driver (1976) with touches of Man Bites Dog (1992) and Natural Born Killers (1994) in which Kurt Kunkle, a low-engagement influencer wannabe who makes a living as a driver for an Uber-like ride-hail service, played by Stranger Things’ Joe Keery, manages to finally attain long-sought-for virality by going on a nightlong murder binge, aided along the way by some savvy stream sniping.

While much content comes of terrorizing an unsuspecting public, quite a bit of it is generated through power struggles within the streaming community, a la Bjørn and EBZ, or EBZ and Billy the Fridge. Streamers form allegiances and rivalries, with an eye to synergizing brands or generating content through conflict. Baked succeeded in running Captain Content off IP2, then had a public falling out with Mando after their road trip, shouldering in on his former partner while Mando gave an interview to local news at a pro-Trump rally in Phoenix, Baked then heading off with a satisfied “Cucked his interview.” In New York City, Sanchez made a show of vying for the content crown of Hampton Grosso, aka Hampton Brandon, who owes much of his own notoriety to his very public beefing with Ice Poseidon, having come to Ice’s home and trashed his patio before later trading punches with Ice in front of the Baja Fresh Mexican Grill on Hollywood Boulevard over the Walk of Fame star commemorating Western star Chill Wills.

Brandon, a tall, athletic white boy with malevolently slinted stoner eyes who returned to his hometown of New York in spring 2020 is a no-joke brawler, cooling his heels in lockdown until late last year for a plethora of charges. Sanchez responded to news of Brandon’s release on his stream, musing “I think the script just got more interesting.” With drama the name of the game, certain streamer rivalries have an air of screenwritten tidiness, and there is consequently a widespread suspicion of the authenticity of the internecine squabbles popping up in this world where, after all, everyone is lying all the time. (A recurring bit occurs when these jackals pump one another up after Macing innocent bystanders, hooting “Yo, you had no choice!” and “Bro, she was assaulting you!” and things of this nature.)

Accusations of kayfabe and general imposture run rampant in chats and threads devoted to IRL streaming, as it does in the world as a whole. This becomes a running joke in Spree—as Kunkle racks up kill after kill, his chatroom fills up with heckles of “FAKE.” But with the bar for content constantly being raised—or lowered, if you prefer—the IRL streams are jarred by eruptions of quite convincing violence, or the threat of it. In November Steel Puma, a Baked lieutenant, was dropped with a flurry of punches from another streamer named Joker, leaving Puma stunned, his MAGA hat spinning on the sidewalk. In September, a Trending Topic emerged concerning Frank Hassle, a professional YouTuber harasser who showed up streaming on the doorstep of longtime target Boogie2988 in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Boogie2988 was there with a gun to greet Hassle, and pumped off a warning shot.

Keeping track of feuds and shifting allegiances is a full-time job. Those wageys—message board slang for those with day jobs—who can’t stay on it in real-time can get their recaps via a variety of venues: not only the /r/LivestreamFails community, a grease trap that preserves the lowest moments of the day, but places like the late CX News, The Rocky Reina Show, or Cognitive Thought, hosted by an Englishman billed as Rooster Cogburn, which did a feature-length episode on the ongoing downward spiral of ONLYUSEmeBLADE. (The theme song for Cognitive Thought, presumably self-recorded, is a glum hip-hop track that announces: “Welcome to the internet, you best prepare your brain.”)

So, too, is it a chore to keep track of the location of the streams themselves. Streamers, whose bread and butter after all is the violation of community standards, are forever being reported and kicked off various platforms, only to then, Whac-a-Mole style, pop up immediately on another. Ice Poseidon moved to YouTube after being banned from Twitch, then migrated to Mixer, then moved back to YouTube after that service shut down. In October, Baked Alaska’s account was removed from YouTube thanks to the efforts of Vic Berger IV and Tim Heidecker, who shared a clip of a Baked stream in which he berates employees at a Chevron station with an implicit request to have Baked deplatformed, earning Heidecker a deeper animus among alt-right adjacent IRL streamers than that which he’d already enjoyed for perceived infractions against controversial comedian Sam Hyde.

The beatifically based Hyde is a figure held in nearly universal esteem in the IP2 community, as such esteem is a rarity here, as streamer-viewer relationships depart from anything that might be termed “fandom.” Streamers’ open contempt for certain viewers of the stream is typical, as is the viewers open contempt for the streamers: locked in a mutually demeaning transactional relationship, both sides are constantly exchanging imprecations in the chats. The streamer knows that the scoptophile viewer cannot look away; the viewer knows the streamer is a monkey dancing for donos, useless without an audience, and the biliousness of the relationship is palpable. In the Attila/Jewel Rancid sex scene he pauses to slur to camera in mid-coitus: “The incels love this.”

Other streamers trade less in open affront to the world than in the spectacle of their own debasement and self-degradation. (You might argue, and not without reason, that all of this only amounts to debasement and self-degradation, but at any rate it does take different forms.) Perhaps the most noteworthy self-sacrifice is ONLYUSEmeBLADE, born Brian Risso, a hardcore alcoholic who first gained notoriety in 2009 with YouTube videos of his Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare play, in which he would cut down opponents using only the knife mechanic. BLADE followed the Ice Poseidon transition from gameplay streamer to IRL streamer, his specialty “drunk streaming,” which he described thusly: “I sit in front of the computer and people donate money for me to take shots and take shots and get stupid and pretty much it’s a shitshow.” In other words, BLADE learned there’s an audience out there eager to see him fall on the knife himself.

Where the spectacle of a Sanchez or a Baked stirring shit offers the viewer to the chance to participate at a distance in addressing the world in an attitude of open disrespect or affront, the attraction of BLADE’s public disintegration is more akin to that of being onlooker to a multiple vehicle collision, with points of interest to date including unwelcome gropings of women, weight gain and muscle mass loss, rape accusations (the abovementioned Goocheese), loss of control of bladder and bowels and, from 2019 to present, the development of slowly worsening and suppurating sores on his legs believed to be connected to his diabetes, the progress of which BLADE’s “fans” have diligently monitored and memed. BLADE’s channel disappeared last November with an announcement that he was leaving content creation, this corresponding to news that his girlfriend, Becky, was expecting twins, the greatest content creation of all.

ON TOUR

BLADE could in 2020 be seen with Baked and others in “RV6,” one of the supergroup-style events that are staples of IRL streaming, the sixth in a series of trips taken by a clutch of streamers in the eponymous recreational vehicle, criss-crossing the highways of America, causing trouble wherever they go, and turning on one another during drunken, debauched nights when no other low-hanging fruit is in sight. If one dysfunctional narcissist is entertaining, a group of them will be more entertaining still—the idea is a staple of reality television, with roots that run through Howard Stern’s Wack Pack, Andy Warhol’s Superstars, and John Waters’s Dreamlanders. (More common message board references are to The Jerry Springer Show and Bumfights, which are probably closer to the practical results.)

In the IRL streaming community, specifically, the origins of the ensemble act may be traced back to the heyday of BattleCam.com and the BattleCam House. BattleCam.com, the social network community connected to the HD internet television provider FilmOn, was the brainchild of Alkiviades “Alki” David, the Nigerian-born Cypriot Greek heir to a fortune built on Coca-Cola bottling plants. After writing, producing, directing, and starring in two indie films seen by precisely no-one, David turned his attention to the world of content, launching the internet-based television provider FilmOn.tv in 2009. (FilmOn also has a music division, and for a time counted Chief Keef as its most significant signee.)

In 2013, FilmOn announced a new “Live Interactive Anti-Social TV Show,” in which six men and six women culled from Alki’s website were confined in a house in East L.A. and would, by responding to truth-or-dare style prompts from the viewing audience, compete for basic amenities and “exit passes” allowing them to leave the house. (Upon entering the outside world, the liberated participants would be followed by a camera crew, and given every financial incentive to create more mayhem.) Said David on the launch of the show, “Jerry Springer is a watered-down version of BattleCam House. I'm sure it’s going to really upset the vocal minority but most will get a kick out of the antics of our BattleCammers.” Pitching the site, David gave a minor tweak to the old Warhol adage: “BattleCam.com provides a platform for any attention seeker to achieve international stardom; now, everyone can be world-famous for 15 seconds from the comfort of their home computer.” While I don’t believe IRL livestreaming has yet produced a Warhol figure, it may yet yield up a Valerie Solanas.

The BattleCam House was followed by David’s Road to Hell, a prank show in which David plays a limo driver who lures men into his car with the promise of On the Prowl-style connubial bliss, then torments them. The challenge-based model of the BattleCam House, taken from game shows and reality television like Fear Factor, was picked up by other content creators, with Ice Poseidon hosting a series of CX Fear Factors. And then there were the communal living situations, like the “Vegas Compound” featuring ONLYUSEmeBLADE, Attila, and a fiftysomething streamer fond of fisticuffs who goes by OG Geezer, engaging in all manner of squiffed, depressing depravity. The RVs took the show on the road, and kept the crew in claustrophobic close quarters sure to generate content, like Billy the Fridge taking off a passed-out BLADE’s sneakers to examine the gangrenous hole in his big toe.

RV6 was bankrolled by Casey Content God, one of the Medicis to the streamer set, who obtained the 2006 Coachmen Mirada which was to be the scene of the rolling debauch. The cast is a revolving door, with streamers joining and departing, often in a huff. In the mix at one time or another, alongside Baked and BLADE, were Carl ii, Demon Andy, Dope District, Johnny Boston, Chaggot, Skimask Andy, Schizo Sammy, Stop Speeding, Aldy1k, Laura, Steel Puma, Shooter McFaggot, and Loulz, a previous unknown who briefly emerged as the trip’s breakout star. Tires blow, and hours are spent struggling to repair them. Much content is created by Baked entering establishments with his TTS on, which invariably starts yapping the Keemstar dono.

There are encounters with cops, and with stream snipers, Loulz among them, who gains fan-favorite status not only for his willingness to not only keep the TTS cranked loud and proud but to augment whatever’s coming in with slurs of his own. Normies are pressed, and then sprayed with bear Mace, referred to by IP2 as “content spray.” Baked, who is officially sober—a point much contested on the message boards—acts as a sort of ringleader and instigator, and he has the best room in the RV. Ample meth is acquired and smoked, not without incident—during one deal Johnny Boston has his phone snatched, leaving Baked and BLADE to negotiate with the thieves for its return. BLADE can otherwise can be relied on to get blackout drunk on Jäger nightly, usually creatively interfered with after he crashes out—at one point an Egg McMuffin is duct taped to his head. As he slumbers, the rot on his legs continues a steady progress towards putrefaction. He is earning, by some at-home- viewer estimates, a princely sum. The Keemstar donos roll in at $20 a pop, and they roll in often.

One of the last stops for RV6 was a visit to a post-election “Stop the Steal” rally in Phoenix, which quickly went pear-shaped. Baked, barking about Jews during an Alex Jones oratory, is rendered silent by a musclebound man in a Superman tank top who tells him “Shut up with Jewish shit… You’re trying to segregate people. There’s evil people of all fucking races. Just shut the fuck up.” Baked goes on to try to ingratiate himself with a pack of Proud Boys, insisting “I know Gavin [McInnes],” but is likewise rebuffed. (That the men might have crossed paths at Misshapes in 2008 seems eerily possible.) On the evening of November 8th-9th, as the RV was struggling back to Los Angeles, its momentum ground to a halt after a member of the crew, Dope District, was arrested with a felony battery charge after fracturing the skull of streamer Aldy1k. RV7 was in the works, along with a streamer house in Mexico, though all of this seemed unlikely after Baked broadcast on DLive from inside the Capitol, resulting in the demonetization of he and other IP2 streamers. Casey Content God, not a man to be easily deterred, went ahead and announced plans for an RV7 in August, 2021—though it was eventually delayed until December.

I, TOO, AM PRESSED

Smooth Sanchez missed RV6 but he was back on the street after his bridge stunt in plenty of time for Halloween, which he spent streaming in the East and West Villages, asking women for their phone numbers between bouts of boasting of himself as “the alpha incel king” and quoting Travis Bickle and “Supreme Gentleman” Elliot Rodger, all while his TTS bubbled with gems like “Fuck all women. You don’t deserve our beautiful cocks.” On ip2alwayswins and KiwiFarms, there was a consensus that all of this was careening towards catastrophe, that you can only press so far and so long in a country that is armed to the teeth, and you can only freebase so much stepped-on shit in a country lousy with Fentanyl, and that someone eventually was going to die by someone else’s hand or their own—which, of course, was the incentive to keep tuning in to these circling-the-drain spectacles.

Previous spectacular flame-outs are still spoken of with reverential awe. A prime example is the last hoorah hurrah of IRL streamer Arab Andy, who was arrested in 2019 after creating a panic in a classroom on the University of Washington campus when his TTS announced “Countdown successfully started,” suggesting a detonation was imminent—when the cops were climbing up the Queensboro Bridge to get Smooth Sanchez down, several variations of this were heard. Arab Andy is back now, with a channel where he discusses K-Pop, but the consensus is that he’d lost his spark in the slammer, and that the old magic is gone.

While Arab Andy, having had his fill of hubris and nemesis, now blabbers about Girls’ Generation for a diminishing audience, the high-wire act continues apace for other IRL streamers, and fuses continues to run down. My friend Bilandic snapped the above pic of Sanchez spotted in the wild on January 17th, at an anti-mask rally in Union Square. This was a few months before feds frog-marched him out of the East Village apartment that he shares with his grandmother, mother, and uncle for having cleared the outdoor dining area at a Flatiron restaurant on Valentine’s Day, shuffling in and announcing “Allah Akbar… Bomb detonating in two minutes.”

Rep and rap sheets grow in tandem. Bjørn may or may not have been detained by the Danish government after making threats to the Prime Minister on his stream, OG Geezer was very definitely stabbed in the leg during a street scuffle, and Chicken Andy was seen driving around with a guy called Crack Rock Johnny looking for guess what controlled substance—this not long after he looked on, dumbfounded, in the parking lot behind the STRAT Hotel in Vegas while his girlfriend, Alice, was beaten into a state of hydrocephalic swelling by former porn actress Bobbi Dylan. IP2’s other favorite amour fou couple, Attila and Jewel Rancid, whose druggy erotic fumblings have been surfacing on sites like Chaturbate and eFukt, were married on March 22nd, and during a brief period of connubial bliss kept the Austin PD occupied with domestic dispute calls—Attila purchased a fire axe and brandished it menacingly to great fanfare, and much ghoulish speculation occurred around the issue of when and how it will be put to use. Smart money had it that Chicken Andy or Stop Speeding, whose pseudonym is a veritable cry for help, were first in line to OD, but early January brought news of the death of RV6 cast member Johnny Boston, born John M. Flaherty, at age 45, a known opiate enthusiast who’d been back home in the Commonwealth, streaming from Beantown’s Methadone Mile. Any memorializing, however, took a backseat to January 6th and the Capitol Hill Follies.

After an adult life spent in breathless pursuit of metrics, the breach of the Capitol at long last elevated Baked from eCeleb to national story, CBS News Los Angeles news identifying him as a “Noted Nazi Miscreant” in a segment describing the ongoing manhunt for implicated riff-raff in the days following that bizarre be-in. Right up to the moment of his arrest Baked was still fave-ing and RTing from a locked Twitter account, but the YOBAstream would soon fall silent as, per court documents: “The judge and federal administrator admonished him to stay off social media.” Another tidbit worth noting: “Gionet’s attorney said his client is a self-employed ‘filmmaker’ but he’ll have to get new employment so he can be monitored.” In the opinion of at least one lawyer, then, when we’re talking about IRL streaming, we’re talking about cinema. Leaving town… gonna do it… blowing loads… making movies…

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to Employee Picks, as that’s the only means I have to receive remuneration for researching and writing it.